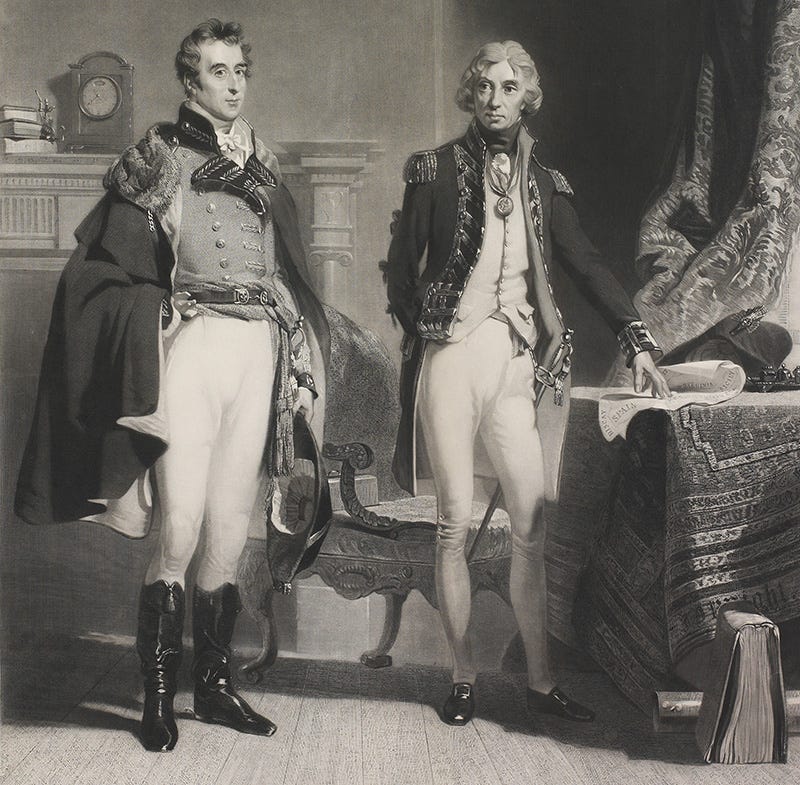

Clash of the Titans, 1805

A navy man, an army man (and a regrown arm!)

(Hello, this is Histories, a weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe to receive it in your inbox for free.)

This time I’m beginning an experiment which you are invited to take part in. I was contacted recently by the creators of a new, free app for iPhone and iPad users, called Threadable. It is designed to make it easy to discuss literary and historical texts by highlighting passages and commenting on them. Rather than just repeat what’s in Histories there, though, I have put together a collection of bonus extra material, called Snapshots of Georgian Life, all from the same source I discuss below. I’d love you to join in the conversation – think of it as something like an online book group, in this case called a Circle. The app is still under development but you can help try it out – and do report your feedback as it will help make improvements. If you download the app to your device, please go to the Circles section and use the code 61001, and I’ll see you there!

He entered at once into conversation with me, if I can call it conversation, for it was almost all on his side and all about himself, and in, really, a style so vain and so silly as to surprise and almost disgust me…

On my local community forum recently someone posted a quotation about the difference in leadership between the Duke of Wellington and Lord Nelson.1 It referenced a famous and rather imperious quotation by the former about his army. In a latter to the 3rd Earl Bathurst on 2nd July 1813, Wellington wrote: “we have in this service the scum of the Earth as common soldiers”. Later, in conversation in 1831, Wellington was only too eager to amplify this notion:

The French system of conscription brings together a fair sample of all classes; ours is composed of the scum of the Earth—the mere scum of the Earth. It is only wonderful that we should be able to make so much out of them afterward. The English soldiers are fellows who have enlisted for drink—that is the plain fact—they have all enlisted for drink.

The point made by the quote contrasting Britain’s two military giants of the Napoleonic era was that Nelson couldn’t have got away with remarks like this, because he had to be “on the same ship” as his men. In modern terms, he had skin in the game. Although in fairness Wellington took part in around 60 battles, and is known for his defensive style which seems preferable to one sending everyone straight to their deaths. His own first experience in battle was in Flanders in 1794, and a fellow officer in a battle in India in 1803 observed “the General was in the thick of the action the whole time”.

Anyway… all this made me wonder whether these Titans of history had actually ever met, given that they were responsible for the two most famous defeats of Napoleon, one at sea at Trafalgar in 1805 and one on land at Waterloo in 1815. It turns out that they met only once, and there are only two written reports of their encounter. The more notable of these has brought me to a writer who was new to me, and whose widespread literary, social and political connections in the era make him an interesting read.2

The writer in question is John Wilson Croker (1780–1857).3 I’ll write more about him next time, but, briefly for now, he was an Anglo-Irish lawyer, politician, literary essayist and reviewer who made enemies and friends alike among the great, the good and notorious people of his day. He was close to the Prince Regent, Sir Walter Scott and Sir Robert Peel (most of the time – they fell out and reconciled); and unpopular with figures such as the historian Thomas Babington Macauley, Alfred Tennyson and the social theorist Harriet Martineau. (You can read some of her scathing obituary in the extra text at Threadable mentioned above.)

One of Croker’s most long-standing friendships was with Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), the Duke of Wellington (he was granted the dukedom in 1814 through serving as the ambassador to France) – they first met in 1808, and you can read and comment on Croker’s first reported encounter with him in the extra text. In the three-volume selection of Croker’s journals and correspondence published in 1884 as The Croker Papers, and from which my extracts are sourced, there are many snippets and anecdotes about Wellington which Croker relates from their conversations.

One such is dated 1st October 1834 at Walmer in Kent. Wellington was Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports from 1829 until his death. He visited the official residence for that role, Walmer Castle, annually in that period and it was there that he died in September 1852; Croker had visited him there on numerous occasions.

In that 1834 account below, Wellington reminisces about his meeting with Nelson, which didn’t get off to a good start. The meeting itself took place way back on 12th September 1805. At this point Wellesley was a major-general, just back from India, where he had fought in support of the expansion of the East India Company’s territory and where his brother Richard had been governor-general. He was reporting to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies to be given his next assignment – the man in question, whose tardiness is mentioned below, was Lord Castlereagh, who famously fought a duel with George Canning (later prime minister) a few years later. Horatio Nelson (1758–1805), meanwhile, was at the peak of his fame, cheered wherever he went thanks to his previous battles with the French and Danish, among others; he was there to consult over an alliance between France and Spain at Cádiz. He was also renowned for his mood swings and vanity.

We were talking of Lord Nelson, and some instances were mentioned of the egotism and vanity that derogated from his character. “Why,” said the Duke,” I am not surprised at such instances, for Lord Nelson was, in different circumstances, two quite different men, as I myself can vouch, though I only saw him once in my life, and for, perhaps, an hour. It was soon after I returned from India. I went to the Colonial Office in Downing Street, and there I was shown into the little waiting-room on the right hand, where I found, also waiting to see the Secretary of State, a gentleman, whom, from his likeness to his pictures and the loss of an arm, I immediately recognised as Lord Nelson.

He could not know who I was, but he entered at once into conversation with me, if I can call it conversation, for it was almost all on his side and all about himself, and in, really, a style so vain and so silly as to surprise and almost disgust me.

I suppose something that I happened to say may have made him guess that I was somebody, and he went out of the room for a moment, I have no doubt to ask the office-keeper who I was, for when he came back he was altogether a different man, both in manner and matter. All that I had thought a charlatan style had vanished, and he talked of the state of this country and of the aspect and probabilities of affairs on the Continent with a good sense, and a knowledge of subjects both at home and abroad, that surprised me equally and more agreeably than the first part of our interview had done; in fact, he talked like an officer and a statesman.

The Secretary of State kept us long waiting, and certainly, for the last half or three quarters of an hour, I don’t know that I ever had a conversation that interested me more. Now, if the Secretary of State had been punctual, and admitted Lord Nelson in the first quarter of an hour, I should have had the same impression of a light and trivial character that other people have had; but luckily I saw enough to be satisfied that he was really a very superior man ; but certainly a more sudden and complete metamorphosis I never saw.”

On the very next day, Nelson left London for Portsmouth to rejoin HMS Victory. He set sail for Cádiz on 27th September, and defeated the French on 21st October not far from there off the cape of Trafalgar, but met his own death. Wellington was in fact present at Nelson’s funeral on 9th January 1806.

In the bonus extra material (install this app and use code 61001), you can find Croker’s first description of his future friend Arthur Wellesley, and another Wellington anecdote in Croker’s fascinating account of a visit to the site of the Battle of Waterloo, only weeks after the battle itself – plus other brilliant glimpses of famous people and scenes in the Regency era. More on those next week!

Thank you, Valerie!

Enjoyed this post about Nelson's character.

But I think it's a bit unfair to say his arm has regrown in the picture! If you look carefully at the right sleeve it's kind of limp, with a funny fold, and the end tucked in his pocket. And Nelson is using his left hand to point to the map, which would be an unnatural pose for most people. (Not that Victorian artists were averse to unnatural poses...)