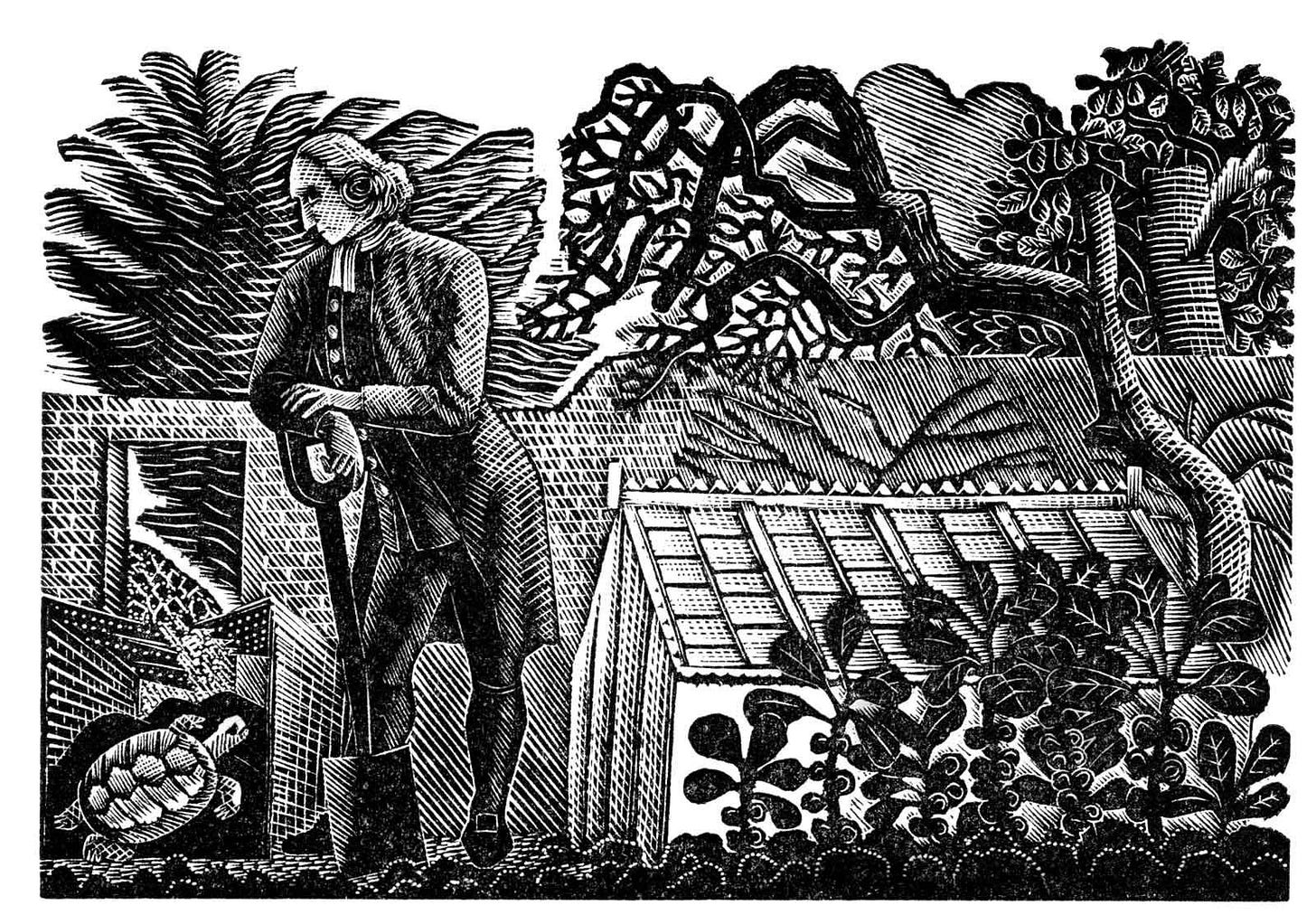

Autobiography of a tortoise, 1784

A 'sorrowful reptile' shares their grievances… (no, really)

Something different this week… Normally I’d give you a short essay, followed by a historical source. But this document is unique, and deserves special attention. Please find below the brief autobiography of ‘Timothy’, penned on 31st August 1784. I have provided a series of footnotes which may help the reader unfamiliar with herpetographical writings!

TO MISS HECKY MULSO1

from the border under the fruit wall

Aug 31, 1784

MOST RESPECTABLE LADY,

Your letter gave me great satisfaction, being the first that ever I was honoured with. It is my wish to answer you in my own way; but I could never make a verse in my life, so you must be contented with plain prose. Having seen but little of this great world, conversed but little and read less, I feel myself much at a loss how to entertain so intelligent a correspondent. Unless you let me write about myself my letter will be very short indeed.

Know, then, that I am an American,2 and was born in the year 1734 in the Province of Virginia in the midst of a Savanna that lay between a large tobacco plantation and a creek of the sea. Here I spent my youthful days among my relations with much satisfaction, and saw around me many venerable kinsmen, who had attained to very great ages without any interruption from distempers. Longevity is so general amongst our species that a funeral is quite a strange occurrence. I can just remember the death of my great-great grandfather, who departed this life in the 160th year of his age.

Happy should I have been in the enjoyment of my native climate and society of my friends had not a sea-boy, who was wandering around to see what he could pick up, surprised me as I was sunning myself under a bush; and whipping me into his wallet carried me aboard his ship. The circumstances of our voyage are not worth a recital; I only remember the rippling of the water against the sides of our vessel as we sailed along was a very lulling and composing sound, which served to soothe my slumbers as I lay in the hold.

We had a short voyage and came to anchor of the coast of England in the Harbour of Chichester. In that city my kidnapper sold me for half a crown to a country gentleman who came up to attend an election.3 I was immediately packed in an hand-basket, and carried, slung by the servant’s side, to their place of abode. As they rode very hard for forty miles, and I had never been on horseback before, I found myself some what giddy from my airy jaunt. My purchaser, who was a great humorist, after shewing me to some of his neighbours and giving me the name Timothy, took little further notice of me; so I fell under the care of his lady,4 a benevolent woman, whose humane attention extended to the meanest of her retainers.

With his gentlewoman I remained for almost forty years living in a little walled-in court in front of her house and enjoying much quiet and as much satisfaction as I could expect without society. At last this good old lady died in a very advanced age, such as a tortoise would call a good old age; and then I became the property of her nephew.5

This man, my present master, dug me out of my winter retreat, and, packing me in a deal box, jumbled me eighty miles in post-chaises to my present place of abode. I was sore shaken by this experience, which was the worst journey I ever experienced.6 In my present situation I enjoy many advantages – such as the range of an extensive garden, affording a variety of sun and shade, and abounding in lettuce, poppies and kidney beans and many other salubrious and delectable herbs and plants, and especially with a great choice of delicate gooseberries! But still at times I miss my good old mistress, whose grave and regular deportment suited best with my disposition.

For you must know that my master is what they call a naturalist, and much visited by people of that turn, who often put him on whimsical experiments, such a feeling my pulse and, putting my in a tub of water to try if I can swim, &c.;7 and twice in the year I am carried to the grocer to be weighed, that it may be seen how much I am wasted during the months of my abstinence, and how much I gain by feasting in the summer.8 Upon these occasions I am placed in the scale on my back, where I sprawl about to the great diversion of the shopkeeper’s children.

These matters displease me, but there is another that much hurts my pride: I mean that contempt shown for my understanding which these Lords of the Creation are very apt to discover, thinking that nobody knows anything but themselves.9 I heard my master say that he expected that I should some day tumble down the ha-ha; whereas I would have him to know that I can discern a precipice from plain ground as well as himself. Sometimes my master with much seeming triumph these lines, which occasion a loud laugh —

Timotheus placed on high

Amidst the tuneful choir,

With flying fingers touched the lyre.10

For my part I see no wit in the application; nor know whence the verses are quoted; perhaps from some prophet of his own, who, if he penned them for the sake of ridiculing tortoises, bestowed his pains, I think, to poor purpose.

These are some of my grievances but they sit very lightly on me in comparison with what remains behind. Know then, tender-hearted lady, that my greatest misfortune and what I have never divulged to anyone before is – the want of society of my own kind. This reflection is always uppermost in my own mind but comes upon me with irresistible force every spring.

It was in the month of May last that I resolved to elope from my place of confinement; for my fancy had represented to me that probably many agreeable tortoises of both sexes might inhabit the heights of Baker’s Hill or the extensive plains of the neighbouring meadow, both of which I could discern from the terrass. One sunny morning, therefore, I watched my opportunity, found the wicket open, eluded the vigilance of Thomas Hoar,11 and escape into the Sainfoin,12 which began to be in bloom, and thence into the beans. I was missing eight days, wandering in this wilderness of sweets, and exploring the meadow at times.13

But my pains were all to no purpose; I could find no society such as I wished and sought for. I began to grow hungry, and to wish myself at home. I therefore came forth in sight, and surrendered myself up to Thomas, who had been unconsolable in my absence.

Thus, madam, have I given you a faithful account of my satisfactions and sorrows, the latter of which are mostly uppermost. You are a lady, I understand, of much sensibility. Let me, therefore, make my case your own in the following manner, and then you will judge of my feelings. Suppose you were to be kidnapped away tomorrow, in the bloom of your life to a land of Tortoises, and were never again for fifty years to see a human face !!! Think on this dear lady, and pity

Your sorrowful Reptile,

TIMOTHY.14

The naturalist, unnamed by Timothy, was a human by the name of the Rev Gilbert White, born in Selborne, Hampshire in 1720. From 1728 until going to Oxford in 1739, he lived at a house in Selborne called The Wakes; he returned there in 1758 and lived there until his death in 1793 – it is now a museum. He is remembered for his Natural History of Selborne and for being, through his close attention to natural detail, a pioneer of ecological thought. We have met him before briefly:

Timothy did not leave any further writings, and died in the spring of 1794. After this it was in fact established that Timothy had been born female. In honour of her unique status, her shell is held to this day by the Natural History Museum – you can see a 3D scan of it here.

Timothy has been suitably celebrated by other authors, notably Sylvia Townsend Warner in her biography The Portrait of a Tortoise (1946) and Verlyn Klinkenborg in his imagining of further details of Timothy’s life, Timothy; or, Notes of an Abject Reptile(2006).

The lady in question was Hester ‘Hecky’ Mulso, 21-year-old daughter of the Rev John Mulso (1721–1791). She had previously written a poem to Timothy, which appears not to have survived, but this letter is the tortoise’s response.

Unfortunately Timothy’s account here must be regarded as fanciful. It has been well established that their species was Testudo graeca, and their origin is more likely to have been North Africa, unless a previous, undocumented kidnapping to America took place.

The gentleman in question was a Mr Henry Snooke from Delves House, Ringmer, East Sussex, and the purchase took place in 1740. The village of Ringmer still remembers Timothy, who is commemorated on the village sign.

Mrs Rebecca Snooke. Mrs Snooke’s nephew, whom we shall meet soon, observed of Timothy on 12th April 1772: “as soon as the good old lady comes in sight who has waited on it for more than 30 years it hobbles towards its benefactress with awkward alacrity, but remains inattentive to strangers”.

The nephew had been a regular visitor to his aunt, not least for the annual September weighing of Timothy. On 8th October 1770, the nephew wrote to his friend Daines Barrington (c.1727–1800), Vice President of the Royal Society: “A land tortoise, which has been kept for thirty years in a little walled court belonging to the house where I am now visiting, retires under the ground about the middle of November, and comes forth again about the middle of April. When it first appears in the spring it discovers very little inclination towards food; but in the height of summer grows voracious: and then as the summer declines its appetite declines; so that for the last six weeks in autumn it hardly eats at all. Milky plants such as lettuces, dandelions, sowthistles are its favourite dish.”

Mrs Snooke died in March 1780, aged 85. Two days after the funeral, her nephew wrote: “Brought away Mrs Snooke’s old tortoise, Timothy, which she valued much, and had treated kindly for near 40 years. When dug out of its hibernaculum it resented the insult by hissing.”

On 31st March 1780, the nephew wrote to his niece Molly (who later helped with the editing of his book): “Timothy the tortoise accompanied me from Ringmer. A jumble of 81 miles awakened him so thoroughly, that the morning I turned him out into the garden, he walked twice the whole length of it, to take a survey of the new premises; but in the evening he retired under the mould, and is lost since in the most profound slumbers; and probably may not come forth for these ten days or fortnight.”

The naturalist described these experiments in his letters: “July 1. We put Timothy into a tub of water, and found that he sank gradually, and walked on the bottom of the tub; he seemed quite out of his element and was much dismayed. This species seems not at all amphibious.” and “Sept. 17. When we call loudly through the speaking-trumpet to Timothy he does not seem to regard the noise.”

In ‘New light on an old tortoise’, in the first 1989 edition of the Journal of Chelonian Herpetology, A.C. Highfield and J, Martin observe: “We note that over the 18 years White had charge of it, its weight fluctuated between 2,835g to 3,260g.”

Indeed, the naturalist was disdainful of Timothy’s lifestyle and habit of hibernation in particular: on 21st April 1780, he wrote, “When one reflects on the state of this strange being, it is a matter of wonder to find that Providence should bestow such a profusion of days, such a seeming waste of longevity, on a reptile that appears to relish it so little as to squander more than two-thirds of its existence in a joyless stupor, and be lost to all sensation for months together in the profoundest of slumbers.”

Lines from John Dryden’s Alexander’s Feast , referring to Alexander the Great’s beloved musician Timotheus.

The naturalist’s manservant.

A leguminous plant used for animal fodder.

This would not be the only time when Timothy went a-wandering, perhaps in search of testudinal society. On 5th June 1787, the naturalist would write: “The tortoise took his usual ramble, & could not be confined within the limits of the garden. His pursuits, which seem to be of the amorous kind, transport him beyond the bounds of his usual gravity at this season. He was missing for some days, but found at last near the upper malt-house.”

my uncle John had a tortoise, Bill, who played the clavichord.

We have two tortoises in our lives, Lettuce and Richard. They are brother and sister, and just over one years old. They are most winning pets, and look not only capable of writing prose but also outliving me.