Appointed to die, 1556

Rain and fire in Tudor Oxford

Coming to the stake with a cheerful countenance and willing mind, he put off his garments with haste, and stood upright in his shirt…

Last week I listed a few previous Histories pieces century by century, and in the course of doing so it occurred to me that I have rather neglected the 16th century. I’ve written before about how the further back we travel in time, the fewer clear first-hand sources we have, but even so, the age of the Tudors hardly went unrecorded. This week, then, I give you a powerful eyewitness account, of a forlorn event but one which epitomises the religious struggles of the era in Britain.

The event in question was the burning at the stake of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, in 1556. Cranmer (born in 1489) had been one of Henry VIII’s key supporters in asserting royal supremacy over the church. Cranmer, installed as archbishop in 1533, had facilitated the annulment of Henry’s first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon, and was one of the founding fathers of the English Reformation which saw the separation of the Church of England from Rome; he was also the author of the C of E’s foundational English-language liturgy, The Book of Common Prayer, in 1549.

But after Henry’s son Edward VI died in 1553 aged only 15, Edward’s half-sister ‘Bloody’ Mary deposed their cousin Lady Jane Grey and began to reassert Catholicism – very much by force. She had no particular reason to favour Cranmer anyway: as Catherine of Aragon’s daughter, she was declared illegitimate on the marriage annulment. By September 1553, only two months after Edward’s death, she had sent Cranmer and other Protestant reformers to the Tower of London.

In March 1554, Cranmer and two of his fellow ‘heretics’, the Bishop of London and Westminster Nicholas Ridley and Edward’s chaplain Hugh Latimer, were moved to the Bocardo prison in Oxford (the door to Cranmer’s cell survives to this day, although the prison has long gone). Cranmer’s trial began in September 1555; he began to recant, and his circumstances improved briefly by removal from prison, but ultimately he failed to convince the new Catholic regime and he was executed on 21st March 1556 by burning at the stake. (Ridley and Latimer had met the same fate five months earlier and the three are now known as the Oxford Martyrs – a cross in the pavement outside Oxford’s Balliol College marks the spot, and the 1843 Martyrs’ Memorial is nearby.)

Remarkably, we have an eyewitness account of Cranmer’s sad end. We only know the author was one ‘J.A.’ of Oxford, who wrote a letter about the experience two days later to a friend (believed to be a rewriting of one written on the actual day). This letter was first published by the church historian John Strype in 1694.1 It’s not entirely unproblematic – in 1895 another church historian, Richard Watson Dixon, noted:

The question is, how could any spectator either remember enough, or take notes copious enough, to reproduce not only all that he saw, but all that Cranmer said, his prayer, his long exhortations to the people? The answer is that no spectator could: and that Strype has greatly manipulated his original, to make a single continuous narrative out of two papers, treating two as one: and to do this has inserted one or two little connecting sentences, and made some transpositions…2

But the authenticity of J.A.’s account isn’t really questioned, and Dixon describes it as “very touching” – all the more so because J.A. was clearly a Catholic, and therefore had no reason to sympathise with Cranmer, other than through basic humanity. An extract of the letter is below.

But that I know for our great friendships, and long-continued love, you look even of duty that I should signify to you of the truth of such things as here chanceth among us; I would not at this time have written to you the unfortunate end, and doubtful tragedy, of T. C. late bishop of Canterbury, because I little pleasure take in beholding of such heavy sights. And, when they are once overpassed, I like not to rehearse them again; being but a renewing of my woe, and doubling my grief. For although his former, and wretched end, deserves a greater misery, (if any greater might have chanced than chanced unto him), yet, setting aside his offences to God and his country, and beholding the man without his faults, I think there was none that pitied not his case, and bewailed not his fortune, and feared not his own chance, to see so noble a prelate, so grave a counsellor, of so long continued honor, after so many dignities, in his old years to be deprived of his estate, adjudged to die, and in so painful a death to end his life. I have no delight to increase it. Alas! it is too much of itself, that ever so heavy a case should betide to man, and man to deserve it.

But to come to the matter. On Saturday last, being the 21st of March, was his day appointed to die. And, because the morning was much rainy, the sermon appointed by Mr. Dr. Cole to be made at the stake, was made in St. Mary’s church, whither Dr. Cranmer was brought by the mayor and aldermen, and my Lord Williams, with whom came divers gentlemen of the shire, Sir T. A. Bridges, Sir John Browne, and others. Where was prepared, over against the pulpit, a high place for him, that all the people might see him. And, when he had ascended it, he kneeled him down and prayed, weeping tenderly: which moved a great number to tears, that had conceived an assured hope of his conversion and repentance.

[Staunch Catholic Henry Cole was Archdeacon of Ely and Provost of Eton. J.A. summarises the sermon but I’ll omit that here.]

And I had almost forgotten to tell you, that Mr. Cole promised him, that he should be prayed for in every church in Oxford… When he had ended his sermon, he desired all the people to pray for him, Mr. Cranmer kneeling down with them and praying for himself. I think there was never such a number so earnestly praying together. For they that hated him before, now loved him for his conversion, and hope of continuance. They that loved him before could not suddenly hate him, having hope of his confession again of his fall. So love and hope increased devotion on every side.

I shall not need, for the time of the sermon, to describe his behaviour, his sorrowful countenance, his heavy cheer, his face bedewed with tears; sometime lifting his eyes to heaven in hope, sometimes casting them down to the earth for shame; to be brief, an image of sorrow; the dolor of his heart bursting out at his eyes in plenty of tears; retaining ever a quiet and grave behaviour, which increased the pity in men’s hearts, that they unfeignedly loved him, hoping it had been his repentance for his transgression and error. I shall not need, I say, to point it out unto you, you can much better imagine it yourself.

[J.A. then describes how Cranmer himself led prayers and exercised his right to speak. Again, I’ll omit the details of his own sermon, other than its powerful conclusion, in which he boldly admits his recantations were to “save my life” and reaffirms his Protestantism…]

“And now, for so much as I am come to the last end of my life, whereupon hangeth all my life past, and my life to come, either to live with my Saviour Christ in heaven, in joy, or else to be in pain ever with wicked devils in hell; and I see before mine eyes, presently either heaven ready to receive me, or hell ready to swallow me up; I shall therefore declare unto you my very faith, how I believe without colour or dissimulation; for now is no time to dissemble, whatsoever I have written in times past.

“First, I believe in God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, &c., and every article of the Catholic faith, every word and sentence taught by our Saviour Christ, His Apostles, and Prophets, in the Old and New Testament.

“And now I come to the great thing that troubleth my conscience more than any other thing that ever I said or did in my life, and that is, the setting abroad of writings contrary to the truth which here now I renounce and refuse, as things written with my hand, contrary to the truth which I thought in my heart, and written for fear of death, and to save my life, if it might be; and that is, all such bills, which I have written or signed with mine own hand since my degradation; wherein I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand offended in writing contrary to my heart, therefore my hand shall first be punished; for if I may come to the fire, it shall be first burned. And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine.”

And here, being admonished of his recantation and dissembling, he said, “Alas, my lord, I have been a man that all my life loved plainness, and never dissembled till now against the truth; which I am most sorry for.” …

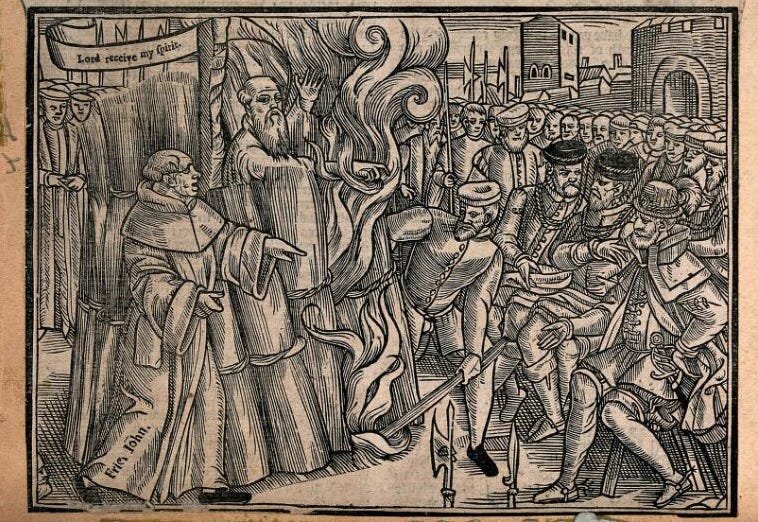

Then was he carried away, and a great number, that did run to see him go so wickedly to his death, ran after him, exhorting him, while time was, to remember himself. And one Friar John, a godly and well-learned man, all the way travelled with him to reduce him. But it would not be. What they said in particular I cannot tell, but the effect appeared in the end; for at the stake he professed, that he died in all such opinions as he had taught, and oft repented him of his recantation.

Coming to the stake with a cheerful countenance and willing mind, he put off his garments with haste, and stood upright in his shirt… Then the bishop [i.e. Cranmer] took certain of his friends by the hand. But the bachelor of divinity refused to take him by the hand, and blamed all the others that so did, and said, he was sorry that ever he came in his company. And yet again he required him to agree to his former recantation. And the bishop answered, (shewing his hand), “This is the hand that wrote it, and therefore shall it suffer first punishment.”

Fire being now put to him, he stretched out his right hand, and thrust it into the flame, and held it there a good space before the fire came to any other part of his body; where his hand was seen of every man sensibly burning, crying with a loud voice, “This hand hath offended.” As soon as the fire got up, he was very soon dead, never stirring or crying all the while.

[J.A. praises Cranmer’s “courage in dying” but cannot accept his beliefs. And here his letter ends…]

His friends sorrowed for love, his enemies for pity; strangers for a common kind of humanity, whereby we are bound one to another. Thus I have enforced myself, for your sake, to discourse this heavy narration, contrary to my mind: and, being more than half-weary, I make a short end, wishing you a quieter life, with less honour, and easier death, with more praise.

The 23rd of March.

Yours, J.A.

Note: If you like the Tudor era, you can get hold of my book about Cranmer’s fellow reformer Thomas Cromwell here (Histories subscribers get the ebook for FREE!):

Strype’s text is online here although I have used a tidied-up version from the 1840s.