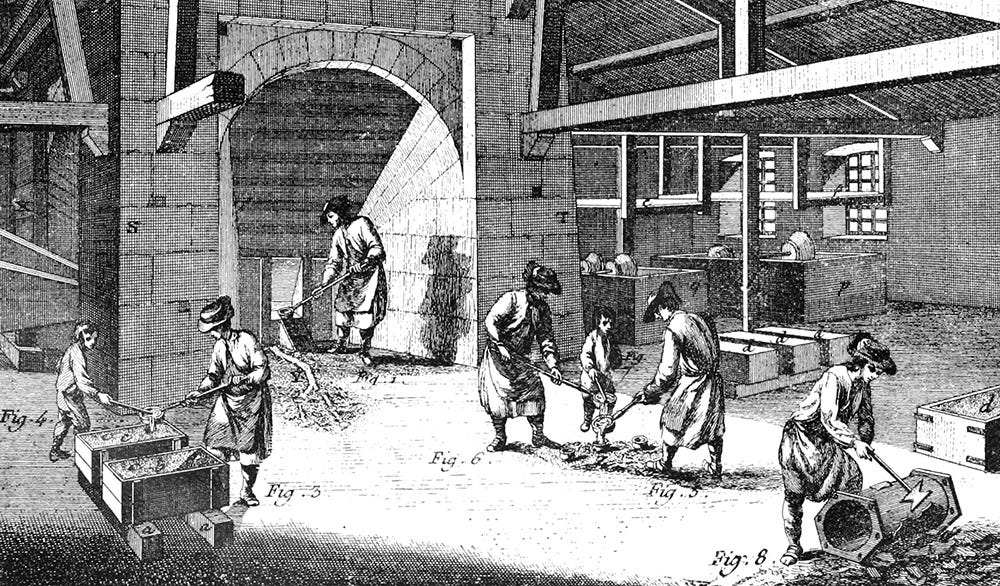

An honest day's work, c.1700

Is 80 hours enough for you?

In my last Histories piece, I wrote about a pre-industrial manual for running a country estate, which contained some useful embedded productivity advice, as well as a lot of assumptions about the labour expected of women. I also mentioned Oliver Burkeman’s thought-provoking Four Thousand Weeks, which has been on my mind a lot. In his book, he refers in passing to an early industrialist, Ambrose Crowley, fulminating against the idleness of his workforce and how he felt “cheated” (Crowley’s word) financially by it. This set me off to learn more and leads us to what could be regarded as a post-industrial follow-up to my previous article.

Burkeman found a note about Crowley in an essay called ‘Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism’1 by the 20th century historian E.P. Thompson, most famous for his book The Making of the English Working Class. It’s an interesting essay, exploring changing relationships with the idea of time, and could lead me to a dozen more articles to write, but let’s focus on Crowley. Here’s what Thompson says about him:

… at the very birth of the large-scale unit in manufacturing industry, the old autocrat, Crowley, found it necessary to design an entire civil and penal code, running to more than 100,000 words, to govern and regulate his refractory labour-force.

Thanks to the wonders of the London Library, I managed to get hold of a copy of The Law Book of the Crowley Ironworks, the code Thompson is referring to, and it’s an extraordinary document, of which I’ll give you but a small sample below.2

Ambrose Crowley was born in 1658, son of a Quaker nail-maker and ironmonger in Worcestershire. Young Ambrose followed in his ferrous footsteps and was apprenticed in London, where he then set up his own ironmongery. He was quick to see business opportunities and in the early 1700s developed a vast ironworks up in Winlaton, County Durham, believed to be the largest in Europe at the time (it made everything from hinges to hatchets, and the original gates for Buckingham Palace were forged there). All of this – and the rest of Crowley’s extensive distribution network across England, fuelled by the Royal Navy being one of his main customers – was managed remotely from his base in Greenwich near the Thames, 300 miles away. The Law Book was part of his solution for this: a codified way of explaining exactly how everything should be run.

Crowley’s star rose quickly – in 1706 he was knighted by Queen Anne and became Sheriff of London. In 1713 he was elected MP for Andover in Hampshire but died only two months later – he was also a major investor in the ill-fated South Sea Company (let’s not overlook that that was a slave-trading enterprise), but didn’t live long enough to see the famous South Sea Bubble economic crash that followed in 1720. Crowley’s business passed to his son John, and it continued to prosper for well over a century – for 54 of those years under the stewardship of John’s widow Theodosia.

Back to the Law Book, though. The ‘laws’ therein – around a hundred of them – were first conceived before 1700, then revised repeatedly over the years. Bear in mind that this is about 60 years before what we think of as the start of the Industrial Revolution (Crowley employed hundreds of people at Winlaton rather than the thousands that became the norm in factories a century later) – yet all the complexities of running a major enterprise are there. Crowley details hundreds of fines for specific infringements, and fosters a culture of informing not just on offenders, but also those who failed to inform on them. There is a hierarchy of committees – but Crowley remains the autocrat (hello, Elon Musk!). Some rules are incredibly specific:

When you send the letters to the posthouse, take care to wrap them in clean brown paper to prevent their being dirtied by the carrier, which oftentimes hath happened. (Law 57, rule 17)

On a more enlightened note, though, Crowley was also a pioneer of a welfare system: financed by means testing and employer contributions, he provided sickness and old age benefits as well as education and medical care. His laws also encompass what we would now think of as a timesheet system for workers.

Here I can only give a small flavour of the Law Book, which reminds us both of the admonitions against idleness in the 1523 document I discussed last time and of the modern surveillance culture of employers such as Amazon. The extract below is from ‘Order 103: Monitor’.

Whereas it hath been found by sundry I have employed by the day have made no conscience in doing a day’s work for a day’s wages… Some have pretended a sort of right to loiter, thinking by their readiness and ability to do sufficient in less time than others. Others have been so foolish to think that bare attendance without being employed in business is sufficient, and at last thought themselves single judges what they ought to do… Others [are] so impudent as to glory in their villainy and upbraid others for their diligence, thinking that their sloth and negligence with a little eye service entitleth them to the same wages as those that discharge a good conscience.

On the other hand, some have a due regard to justice and will put forth themselves to answer their agreement and the trust imposed in them and will exceed their hours rather than the service shall put forth themselves to answer their agreement and the trust imposed suffer.…

To the end that sloth and villany in one should be detected and the just and diligent rewarded, I have thought meet to create an account of time by a Monitor, and do order and it is hereby ordered and declared from 5 to 8 and from 7 to 10 is fifteen hours, out of which take 1½ for breakfast, dinner, etc. There will be then thirteen hours and a half neat service, which being multiplied by six is 81 hours, which odd hour is taken off. Also to the end there may be no disputes in the Monitor’s giving me the turn of the scale and the parties that charge their own time have no pretence to overcharge me, it is hereby declared that the intent and meaning of eighty hours must be in neat service after all deductions for being at taverns, alehouses, coffee houses, breakfast, dinner, playing, sleeping, smoking, singing, reading of news history, quarrelling, contention, disputes or anything else foreign to my business, any way loitering or employing themselves in any business that doth not altogether belong to me.

[And of course the monitor is to be monitored…]

…the Monitor is to lie every night over the Ironkeeper’s office, the Nailkeeper’s or Surveyor’s office, and be every morning in his office before 5 of the clock, and that he always entereth down the minute of his first coming into his office; and for the greater certainty of his integrity, the first person he seeth that is in the Monitor’s List, he is to desire them upon their time paper to mention the day, hour and minute, in words at length, of his being in his office, which is where the minute dial is fixed and at no other place to be entered or commenced from…

Every Saturday morning the Monitor is to carry the book of time to the Accountant, first subscribing to it these words: “This account of time is to the best of my knowledge true and in all respects conformable to the Monitor’s Order No.. [103]…”

[There’s a lot more detail, from a system of examining grievances to more personal grumbles on Crowley’s part – he seems to have a particular grudge against his barrel-makers…]

I have been most horribly abused by the coopers not doing a day’s work as they ought, but have imagined that when they have done what coopers do in piece work that cometh to their wages they have done sufficient… And to the said end I may have an honest day’s work as I honestly pay them their wages, I do order that upon the cooper’s particular absent time paper, he entereth thus:

Saturday – Made 5 half barrels

Monday – Sawed and split clap boards sufficient to make 10 dozen half barrels, stowed

Tuesday – Put on 100 hoops in trimming old casks

Wednesday – Made six kilderkins [half-barrel sized casks]

Thursday – Headed up 10 half barrels, 2 hogsheads, 4 barrels, and made 5 half barrels

Friday – Took in 2000 hoops as per Claim 2348, stowed them, the weigher being sick, helped in the warehouse 11 hours.

[With Ambrose thus preoccupied, let’s sneak away while he isn’t looking…]

The Law Book of the Crowley Ironworks, ed. M.W. Flinn, The Surtees Society, 1957. I have lightly modernised spellings in the extracts used.

How exhausting. Fascinating to read about industry before the Industrial Revolution!