A history of… typewriters (Part 2)

In the words of Mark Twain, "It piles an awful stack of words on one page."

In my previous piece I described how, over the course of the 19th century, there were numerous different typewriters invented, but only one of the ones I described ever entered production, and even that sold fewer than 200 devices. The last in this long list of failures was the Pterotype, patented by John Pratt in 1867 which though it did not succeed itself, it did inspire others to success. His invention gained wide publicity and led to a review in Scientific American, published on the 6th of July of the same year which prophesied that “the weary process of learning penmanship in the schools will be reduced to the acquirement of writing one’s own signature and playing on the literary piano.”1 One person who read this article was an amateur mechanic from Milwaukee, Carlos Glidden (1834–1877) who showed it to his friend, a printer named Christopher Latham Sholes (1819–1890). Sholes already had some experience in this field having invented a machine to print the page numbers onto books and serial numbers on tickets, and Glidden had been pestering him to see if it could do letters as well.

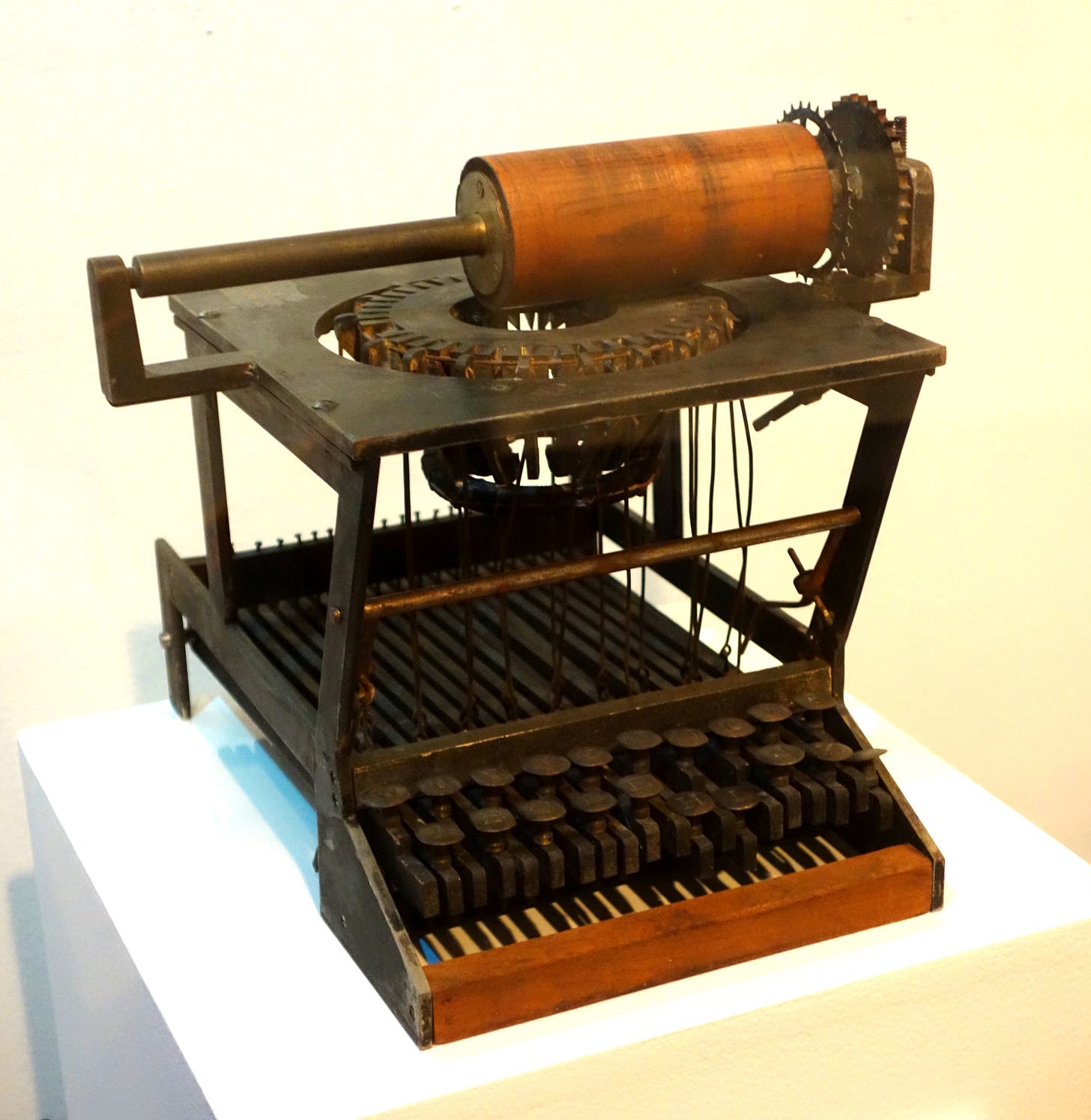

Sholes thought that Pratt’s design was “complicated and liable to get out of order" and believed that a better solution could be developed. He roped in fellow printer Samuel Willard Soulé (1830–1875), who had helped develop the numbering machine, and three of them got to work. By late 1867 they successfully produced a device, but it doesn’t look a lot like the typewriter that we know today; indeed it was described as a “cross between a piano and a kitchen table”. Despite this, they used their machine to type out letters, which they sent to friends, seeking investment in the venture. One of them, James Densmore, was so impressed that he offered them $600 (around $50,000 in today’s terms) for a 25% stake, despite the fact that he hadn’t actually seen the machine. When he did, in March 1868, he was somewhat shocked and declared that it was “good for nothing except to show that its underlying principles were sound”. Nonetheless they obtained a patent for their invention in June of 1868 and Densmore rented a building in Chicago to start manufacturing them in earnest. They were, however, only able to make and sell 15 units before running out of funds and heading home. So far, so much like all of the other tales of typewriter inventions, but they sucked up this knock-back and went back to the drawing board.

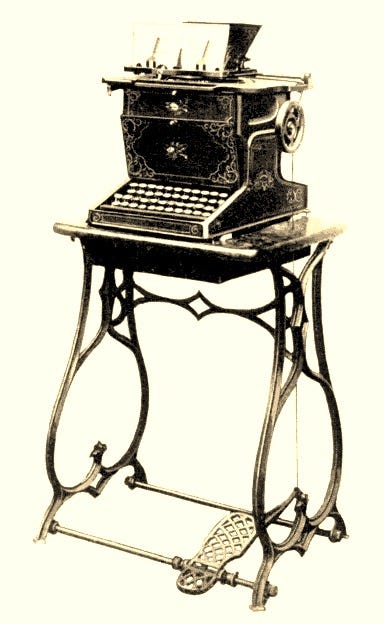

Over the next three years they created dozens more prototypes, drawing upon many of the ideas of earlier typewriter inventors. All of this took cash and yielded precious little income, which caused Soule and Glidden to give up on the venture and sell their stakes to Densmore and Scholes. Some limited production runs took place, but the product simply wasn’t good enough to take hold. In early 1873 Scholes too decided to throw in the towel, and sell his stake to Densmore for $12,000 (around half a million dollars today). His timing may not have been ideal, as in March of that year Densmore signed a deal with the arms and sewing machine manufacturer Remington to start making the machines. In conjunction with Remington’s engineers (notably J. Fay and W. J. Jenne) the cumbersome, ugly, error-prone device was turned into a sleek, treadle-operated device resembling a sewing machine. In fact, Remington explicitly drew the parallel in their marketing. As one contemporary ad proclaimed, “The writing machine is to the pen what the sewing machine is to the needle”, and early models were even sold mounted on sewing-machine stands with foot treadles This messaging helped the public grasp the invention: like the sewing machine had mechanised stitching, the typewriter mechanised writing. Remington painted floral decals on the black enamelled casing, boasting it was “an ornament to any parlour”.

Was this the start of the typing revolution? Not quite. The “Remington No. 1” went on sale in mid-1874 but they only managed to sell 400 machines in their first six months. In part this was the price, $125 (around $10,000 today) – businesses were skeptical in investing in something that might turn out to be fad and individuals simply didn’t write that much for it to make sense. The typewriters were also still, even after much refinement, temperamental and in need of frequent attention. Finally, there was a third, more cultural, problem. In offices still proud of elegant penmanship, the typewriter’s uniform print seemed impersonal and even insulting to some recipients. Anecdotes abounded: one indignant client (allegedly a Kentucky mountaineer) is said to have returned a typed letter with scrawled feedback, “You don’t need to print no letters for me. I kin read writin’.” The problem was that previously letter writing had always been a personal craft, and this new device blurred the line between individual correspondence and printed matter.

There were some early enthusiasts, however, most notably one Samuel Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), who wrote to his brother, Orion Clemens, on December 9th 1874:

I am trying to get the hang of this new-fangled writing machine, but am not making a shining success of it. However, this is the first attempt I ever have made, & yet I perceive that I shall soon & easily acquire a fine facility in its use. … The machine has several virtues. I believe it will print faster than I can write. … It piles an awful stack of words on one page. It don’t muss things or scatter ink blots around.

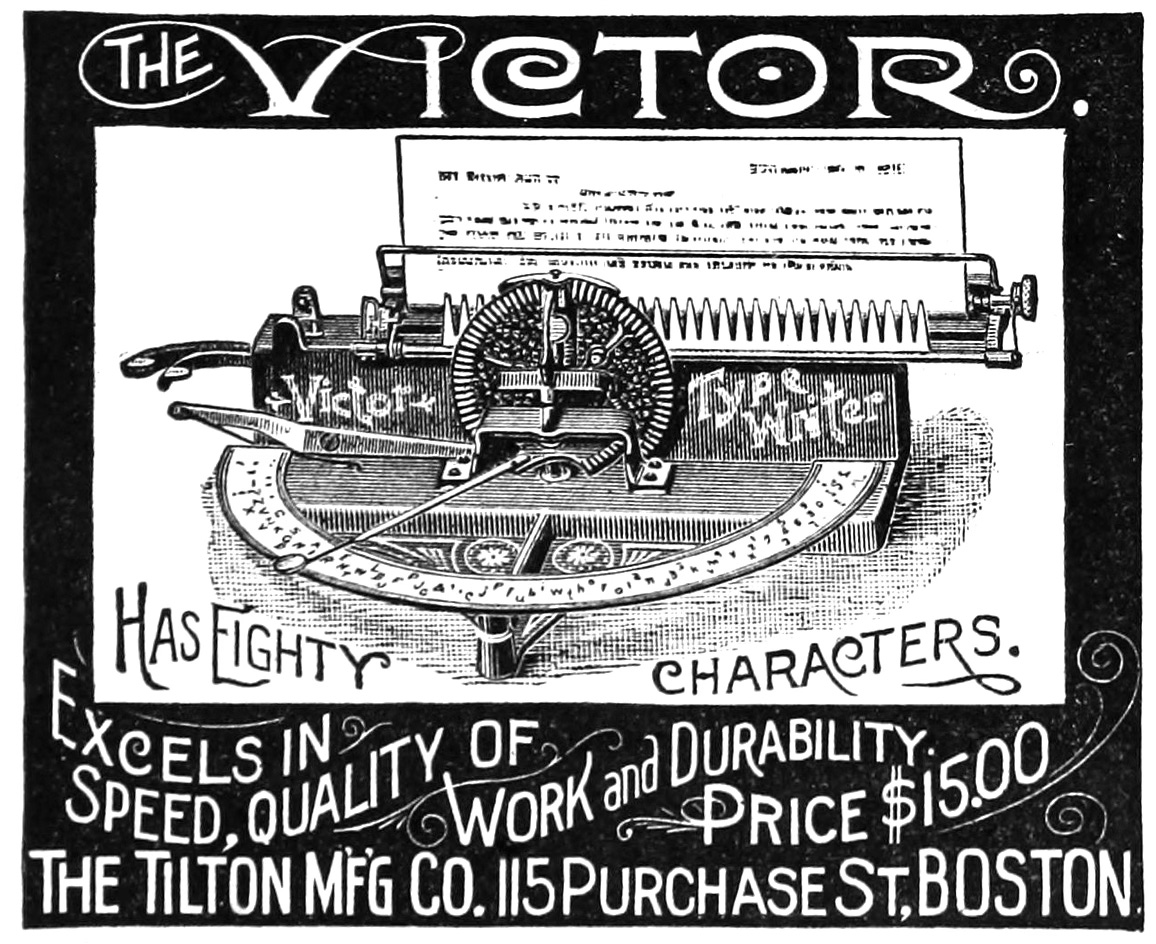

By 1877 only 4,000 machines had been sold, but things improved materially with the launch of the Remington No. 2 in 1878 which, through the introduction2 of the shift key, allowed the user to type in both upper and lower case letters – yes, the first model was all caps (which may well explain why some recipients of letters produced on it found them somewhat off-putting!). In the early 1880s a number of competitors started to enter the market with their own designs. Some, such as the Victor, took a radically different approach (see earlier image) but these failed to succeed. Most copied the same broad design as the Remingtons, including the QWERTY keyboard layout that we are all familiar with today. Now you may have read that this keyboard was designed specifically to separate common letters in order to reduce typebar jams. As the mechanisms of these early machines were somewhat slow, then it made sense to slow the typist down in order to stop two type slugs getting stuck together. This is probably part of the story, but more recent research suggests that this layout also aided telegraph operators (an important early market) when they were transcribing Morse Code.

Over the next decade the quality and popularity of typewriters increased significantly, and the benefits to businesses in particular became clear, as P. G Hubert noted in the June 1888 edition of The North American Review:

…with the aid of this little machine an operator can accomplish more correspondence in a day than half a dozen clerks can with the pen, and do better work.

Having sold the rights to his invention, Christopher Sholes didn’t benefit financially from this boom, but he did take comfort from the social changes that it wrought: “I feel that I have done something for the women who have always had to work so hard,” Sholes reflected near the end of his life, “This will enable them more easily to earn a living.”

Hubert agreed with him, as his piece went on to say:

[a] most excellent feature of this new profession for women is that it pays according to skill and education. Any bright girl in from three to six months may obtain sufficient facility with the typewriter to make herself valuable in an office, and after that everything she does adds so much practice. The salaries of good typewriters average … $15 to $20 a week, … it is a very poor sort of typewriter who, after six or eight months’ experience, cannot make as much at this work as at school-teaching.

By the late 1890s, the typewriter was here to stay – but it was about to get a major upgrade. Early Remingtons and their rivals were “blind writers”, meaning the text was printed on the underside of the platen (the roller) and remained out of sight until one removed the page. Typists had to trust their fingers and only check for errors after a line or two, a cumbersome system at best. The next leap in design was to make writing visible – to let operators see their work as it was being typed. Several upstart companies pursued this goal, but one machine emerged to define the new standard: Underwood.

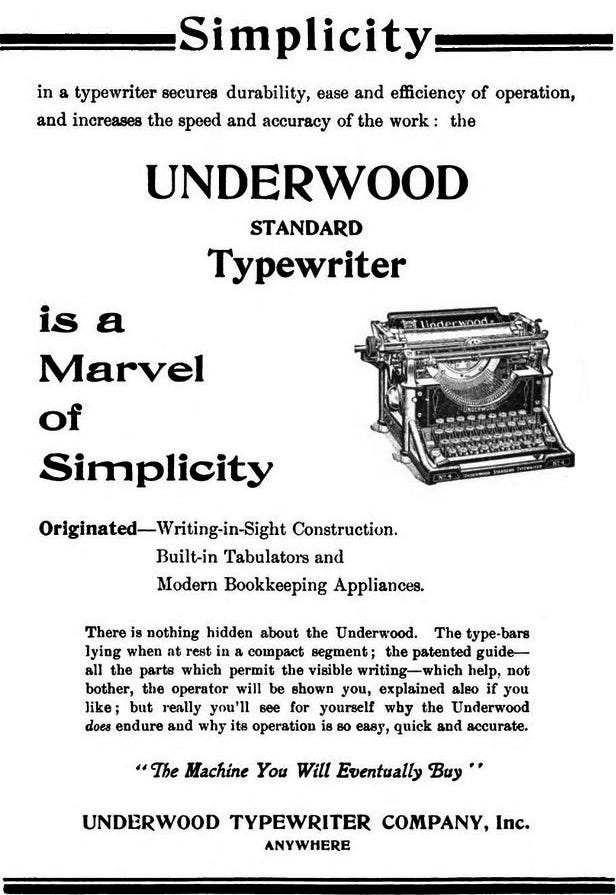

The Underwood typewriter, first produced in 1895 (and popularized by the Underwood No.5 in 1900), moved the type-bars to the front of the platen and introduced a four-row straight keyboard. Now each keystroke struck the paper on the front, in full view of the typist. “Visible writing” was a revelation. An Underwood advertisement from 1909 proudly declared it “The Machine You Will Eventually Buy,”

Within a few years, Underwood had seized the market from older blind-writer makers like Remington and Smith-Premier. By 1915, an Underwood brochure could boast that “there’s but one absolutely visible typewriter… See what you are doing – as you do it.” Visible typing not only reduced errors; it made the whole experience more intuitive. As one typist recalled, it was like lifting a veil: “I no longer felt like I was typing in the dark. With the Underwood, I could watch the words march across the page.”3

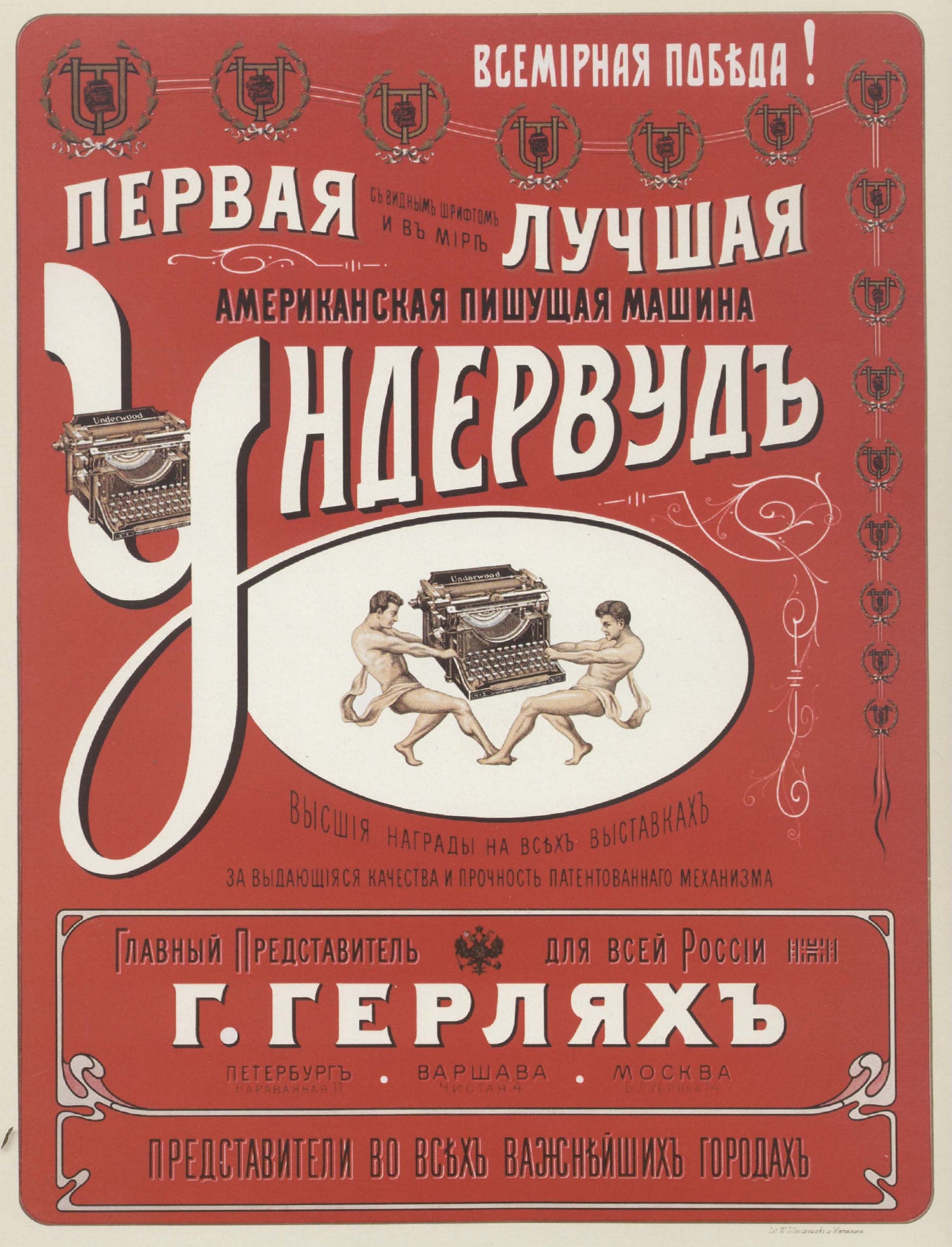

At the start of the 20th century American firms were selling machines across Europe, Asia, and South America, adapting keyboards to local scripts – QWERTZ for Germany, AZERTY for France, even special characters for Spanish ñ or Portuguese ç. If there were strange alphabets or syllabaries, the engineers would find a way to put them on keys. By 1910 you could obtain a Cyrillic Remington in Moscow, an Arabic Smith Premier in Cairo, a Kana typewriter in Tokyo.

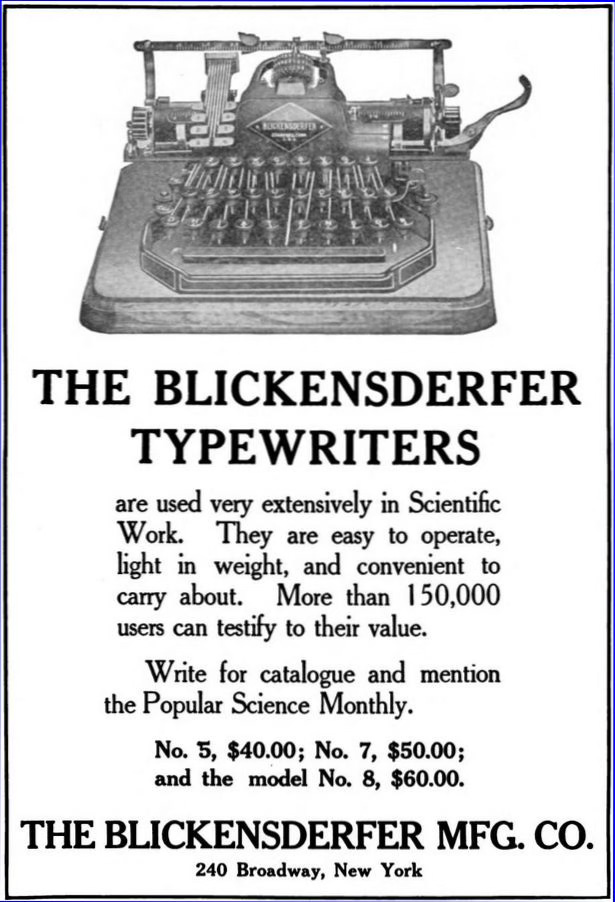

The next development in typewriters related to their size. Early standard machines were heavy cast-iron beasts, 25–30 lbs (11-14 kilos), often bolted to office desks. This was impractical for traveling businesspeople, journalists in the field, military officers on campaign, or simply anyone who wanted to move one around their house. The solution came from innovators like George Blickensderfer, whose Blickensderfer No.5 (1893) amazed people by fitting a full keyboard machine into a petite wooden case with the whole thing weighing less than 7 pounds (3.25 kilos). Soon, other companies followed. The Standard Folding Typewriter (later known as the Corona) came out in 1906 in the US, featuring a folding carriage that allowed a standard four-row keyboard to collapse into a compact size. It weighed about 9 pounds (4kg) and could be set up anywhere – a hotel room, a battlefield dugout, a railway carriage. By 1912, the Corona 3 (an improved model) became wildly popular, selling thousands to itinerant professionals and WW1 military officers (the British Army ordered them en masse for field use).4

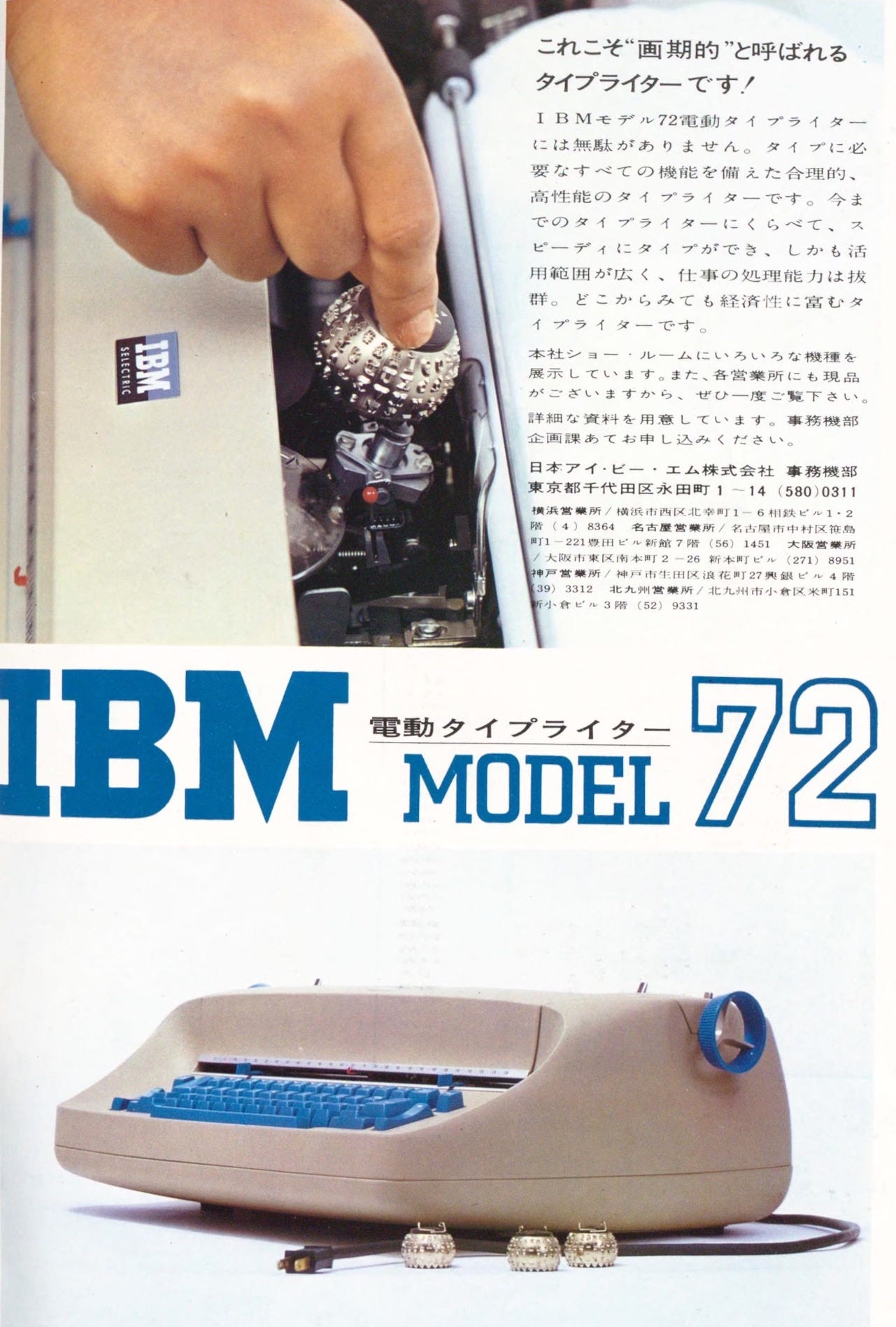

The final evolution of the typewriter took place on July 31, 1961, when reporters and office equipment dealers packed an auditorium in New York City for a much-hyped announcement by IBM. Covered by a veil on stage sat a typewriter that looked like something out of science fiction – sleek lines, futuristic curves, and crucially, no typebars. When IBM’s spokesman unveiled the Selectric Typewriter, the audience saw a machine whose type element was a spherical ball that rotated and tilted to imprint letters. A gasp went up. The Selectric had no moving carriage; the paper stayed put while the “golf-ball” element darted across the page on a pivoting arm. It could type faster and with less jamming, and could change fonts by simply swapping out the typeball. As The New York Times reported the next day:

An electric typewriter that eliminates the customary typebars and moving carriage was demonstrated by International Business Machines… The machine’s spherical typing element can be changed in seconds to provide any of six different typefaces.

Electric typewriters were not new in 1961. IBM itself had been making them since the mid-1930s, after acquiring the Electromatic Typewriter Company. Early IBM electric models (like the 1935 Model 01 and the postwar Model B) still resembled traditional typewriters but used motors to drive the typebars, resulting in a lighter touch and quicker action. These found a niche in corporate typing pools where output quotas were high, but they never went mainstream. By 1958, IBM held a majority share of the US electric typewriter market, yet the basic mechanism – moving carriage, individual typebars – remained the same as the 1880s. The Selectric changed all that, arguably the biggest design leap since the shift to visible typing more than sixty years earlier.

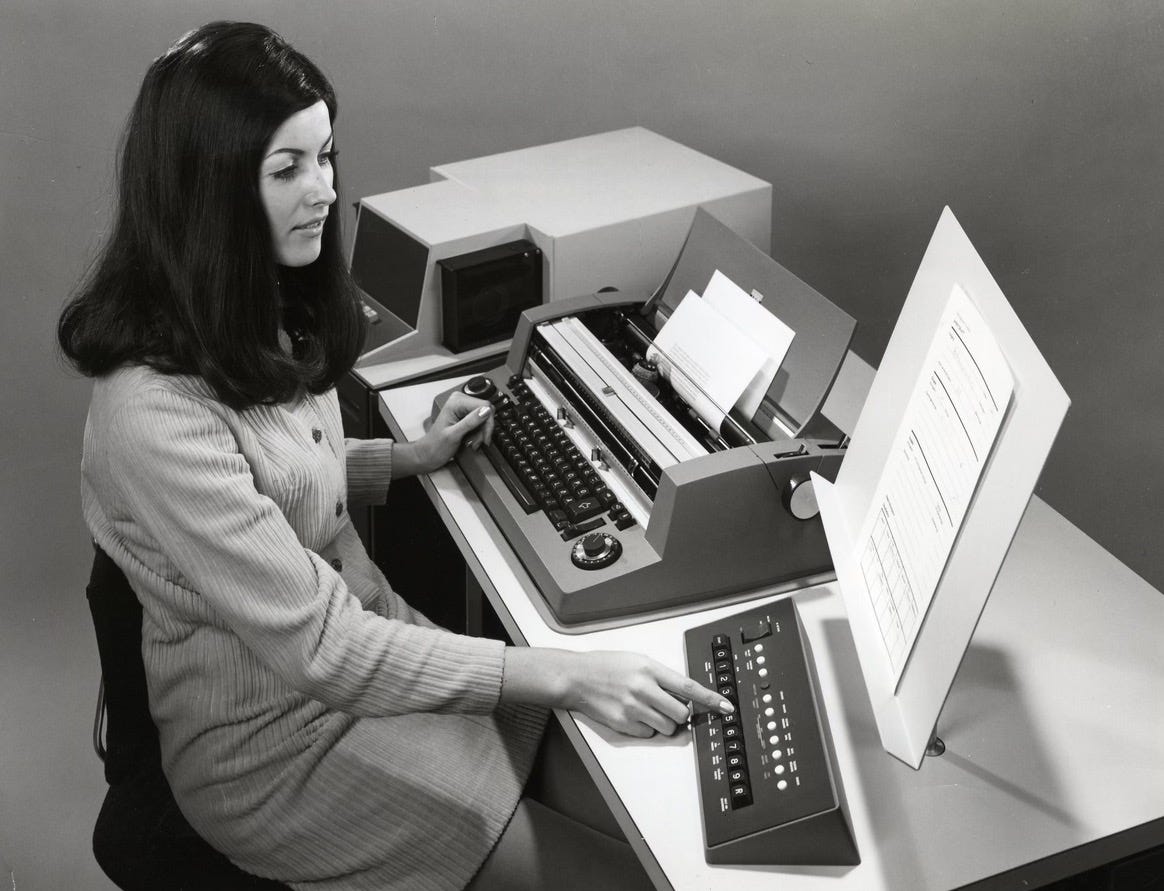

At their peak tens of millions of typewriters were sold globally each year. Today that number is counted in the tens of thousands. IMB sowed the seeds of their downfall, only a couple of years after the launch of the Selectric. In 1964 they launched the world’s first word processor (the term “word processing” derived from the German Textverarbeitung, often credited to IBM’s Ulrich Steinhilper) the snappily named Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter (MT/ST), which let typists record, edit and replay text from magnetic tape. This was, to be fair, closer to a typewriter than what we would think of as a true word processor, but it got the ball rolling.

By the early 1970s, the word processor was a stand-alone workstation with a keyboard, storage and – crucially – a CRT screen for on-screen editing. Firms such as Lexitron and Linolex shipped CRT systems in 1972; Vydec followed in 1973, notably incorporating floppy diskettes for document storage and portability – an important usability leap for office workflows. Wang then hit it big with the Wang 1200/WPS (1976) and later OIS lines, which became fixtures in corporate typing pools and law offices. The explosion of personal computers, and word-processing programmes such as WordPerfect5 which launched on the machines in 1982, sounded the death knell for the typewriter. Though I will likely never use one again, I am fond of the fact that they have left their mark upon how I type to this day.

This has, now, basically happened for me at least. I scarcely ever write anything by hand these days apart from shopping lists and cards.

They also got rid of the sewing machine style foot treadle to power it, which, I suspect, also helped a great deal.

I am sure that this describes a real experience, but the phrasing of this seems a bit too perfectly suited for use in advertising to be wholly genuine.

They were still not cheap – $40 on that 1909 advert is over $2,000 today.

In a cliched “it can’t have been that long!” reaction I just realised that I first used WordPerfect around forty years ago…

A really good article; just missing a reference to the brief appearance of the ‘daisy wheel’ before typewriters finally bit the dust.

I had a toy typewriter with a wheel that you rotated to select the letter. You then thumped on a lever to smack the letter onto the paper. Maybe it inspired the IBM design team to develop the golfball typewriter!

https://oztypewriter.blogspot.com/2012/06/tipp-co-mettoy-and-marx-toy-typewriters.html