A history of… the typewriter (Part 1)

An early device was "intended for the nervous"…

I draft each of these pieces in a Google Doc1 and, once complete, I cut and paste them into Substack. But before I do that I have to run a “find and replace” – looking for every double space in the document and replacing it with a single one. This is because I learned to type on a manual typewriter in the early 1980s, and was taught that there had to be a double space after every full stop. The reason for this is that typewriters use a monospaced font, and you have to do this to make it look right, otherwise the gap would be too small. When I started using word processors in the late 1980s this was still the custom, in part because the early software wasn’t always great at automatic spacing, and in part because that was just what people had always done. But soon automatic spacing was universal, and by the early 21st century style guides converged on single spacing as the standard. But that was too damned late for me. I already had thousands of hours of typing under my belt, and the muscle memory that causes me to double-tap the space bar with my right thumb after every full stop has proved impossible to break. All of which is a very long-winded way of saying that this week I will be exploring the history of the typewriter.2

In July of 1808 in Fivizzano, Italy, Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano3 sat in a dimly lit study before an odd contraption of keys and levers. The fact that it was all but impossible to see in the room didn’t matter to the Countess – she had been blind from birth – and, possibly smiling at the novelty of the experience, she leant forward, laid her fingers on the keys, and began creating the earliest known typewritten document. We know from her surviving letters a little bit about both the design of the machine and her experience of using it. It could work using either ink, or a form of carbon paper, and was more akin to a printing press than a modern typewriter:

Mio caro amico, voglio provare se i caratteri novi scolpiscano meglio col l’inchiostro o col la carta nera…

My dear friend, I want to try whether the new characters take an impression better with ink or with black paper [carbon paper] …

Appena ristabilita dal mio fiero dolore di testa mi sono trattenuta con voi per mezzo della stampa, come vedrete dal foglio che vi ho mandato…

…as soon as I recovered from my fierce headache I kept company with you by means of the press, as you will see from the sheet I have sent you.

Mi si è guastata la stamperia; la tavoletta non chiude più…

…my little press has broken; the tablet/board no longer closes …

Sadly, little else is known about this machine. The “dear friend” to whom she refers is Pellegrino Turri, a Garfagnana-born noble who settled in Reggio Emilia and who created the device that she was using, but again, not much else about his life survives. It is possible that he invented the device, but it is more like that Agostino Fantoni devised an earlier “stamperia” in 1802 for his blind sister and that Turri refined it and developed carbon paper.

It is also possible that, almost a century earlier, another device existed about which we know even less. In 1714 and English engineer named Henry Mill petitioned Queen Anne for a patent on:

an Artificial Machine or Method for the Impressing or Transcribing Letters, singly or progressively one after another as in Writing, whereby all Writing whatever may be engrossed in paper or parchment so neat and exact as not to be distinguished from print.

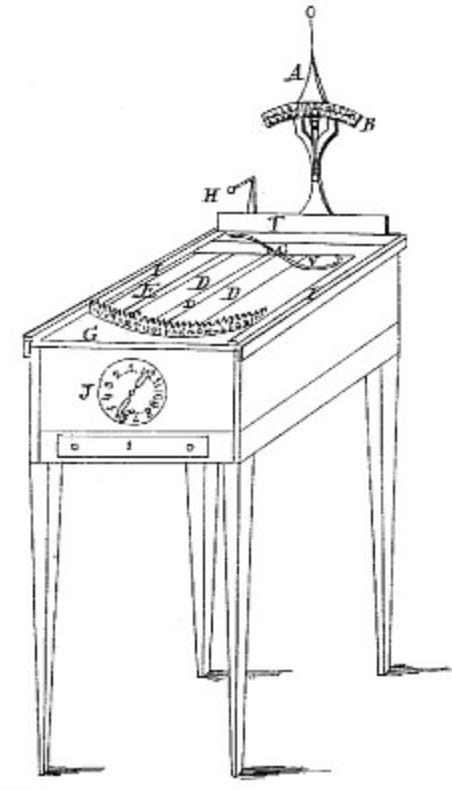

It appears, however, that this machine was never even constructed. The next person on the scene was the American William Austin Burt (1792–1858) who on on July 23, 1829, received US X-patent 5,581 for a “Printing Machine Styled the Typographer”, which explains:

This patent discloses the actual construction of a type writing machine for the first time in any country. The type are arranged on the under side of a segment carried by a lever pivoted to swing vertically and horizontally. The desired character is brought to the printing point by moving this lever horizontally to a position over the same character in the index and the impression is made by depressing the lever.

Several styles of type may be used, and they are arranged in two rows on the lever; these rows of type can be shifted on the lever to bring either one to the printing point. The paper is carried on an endless band which travels crosswise of the machine, and this band is moved for letter space by the impression lever every time said lever is depressed to print. The line space is made by shifting the frame carrying the printing mechanism toward the front or rear of the machine, the paper remaining stationary.

Ink pads are located at each side of the impression point, and all the type except the one in printing position are inked every time the impression lever is pressed. A dial is provided which indicates the length of paper in inches which has passed the printing point in printing each line, and as the operator knows the width of the paper being used, the time to stop printing at the end of the line is indicated.

As you will have guessed from both the description and the picture, this device was very different from what we would consider as a typewriter (and it seems likely that the earlier device, with individual keys, would be more familiar to us). Either way, it was not a commercial success, and one model that we know was built, and lodged with the Patent Office, was destroyed there in a fire in 1836.4 Possibly due to its cumbersome nature, and cost, the product failed commercially.

In 1843 we see another attempt, with American Charles Thurber patenting “Thurber’s Patent Printer”:

This machine is intended as a substitute for writing, where writing with a pen is in convenient by reason of incompetency in the performer. It is specially intended for the use of the blind, who, by touching the keys on which raised letters are made and which they can discriminate by the sense of touch, will be enabled to commit their thoughts to paper. It is intended for the nervous, likewise, who cannot execute with a pen. It is useful for making public records, as they can be made, with this machine as accurately as with a common printing-press. It is intended for those who wish to keep a legible record of daily events, so that they may be read with ease and dispatch by others; and the various useful purposes to which it may be applied will readily suggest themselves to everyone.

Alas he himself admitted that the device was slow and crude, and it too was never manufactured en masse.

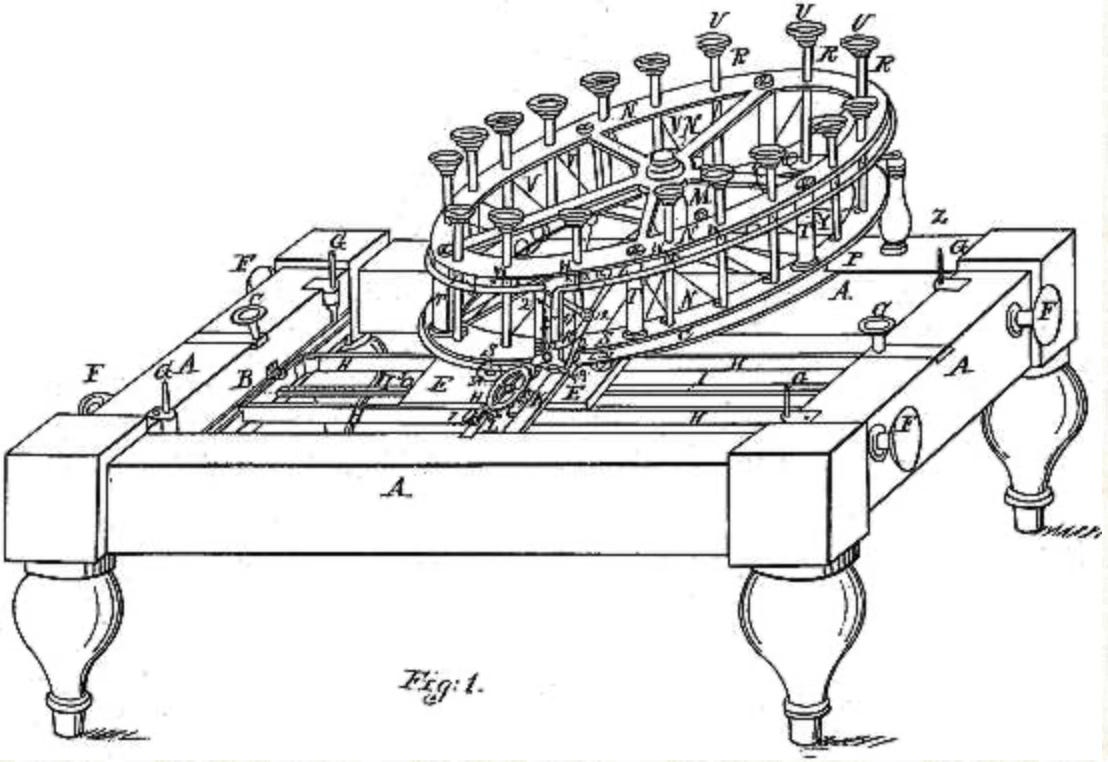

Next on the scene we have the Italian Giuseppe Ravizza (c. 1811–1885) who spent almost 40 years attempting to perfect the typewriter. In 1855 he patented what he called “cembalo scrivano o macchina da scrivere a tasti” (“scribe-harpsichord, or key-operated typewriter”). This had 31 keys5 and a space bar arranged on two rows, each key linked by wooden levers to a type hammer weighted with lead shot for a crisper strike. The hammers (“martelletti”) are arranged in a circle around an inner brass ring on iron posts—bringing multiple types to one point, like later up-strike machines. There was an ink ribbon, a bell that dinged to let you know that you had reached the end of a line and a cord to pull to cause the carriage to return. All in all it had most of the features of what we would think of as a typewriter today. Ravizza continued to tinker with, and improve, the machine over the decades that followed but (and you may be detecting a theme here) the device was never produced at scale. Each was hand-built and of around 16 even produced and of these perhaps only half were sold.

Then we have Peter Mitterhofer (1822–1893), a South Tyrolean carpenter sometimes described as “the inventor of the typewriter”.6 His initial device, built in 1864 may not seem like a good start – it didn’t so much type as tattoo. Instead of metal letters, it used a forest of little needles to perforate the page in a flat frame. His next design, fairly sensibly, replaced the needles with printer’s metal types, and was sufficiently impressive to get funding from the Austrian state to continue his work. His later models in introduce the shift key (to swap between upper and lower cases) and a cylinder around which the paper is held (rather than, as with earlier designs), a flat metal plate. Unfortunately (and I am sure that by now this will come as a great shock to you) his designs never went into mass production and only a few were ever built.

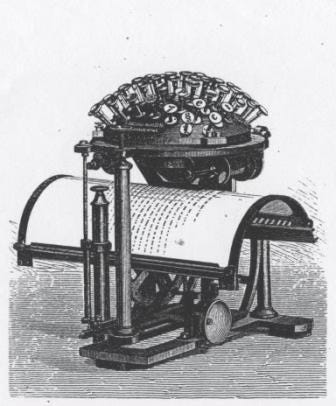

Rasmus Malling-Hansen (1835–1890) was a Danish pastor and head of Copenhagen’s Royal Institute for the Deaf. In the mid-1860s he began experimenting with a device to let people produce text quickly and legibly – an aid for education and office work. By 1865 he had the working concept that would become the “Writing Ball”, later recognized as the first serially manufactured writing device/typewriter. Rather than a flat board, Malling-Hansen arranged 50-odd keys on a brass hemisphere—the “ball”. He tested letter placement (reportedly with a porcelain mock-up),7 putting the most common letters under the fastest fingers, generally grouping vowels to the left and consonants to the right. Each key drove a short piston straight down to a single printing point, minimizing motion and boosting speed. Early models typed onto paper clipped around a small cylinder; a separate “coloring sheet” (carbon paper) or ribbon supplied the ink. Striking a key forced its type to the common point while the paper advanced. Interestingly, Malling-Hansen’s first production machines used an electro-magnet to step the carriage, an early electromechanical assist. He replaced that with a purely mechanical escapement in later versions but nonetheless this can been seen as something of a forerunner to later electric machines.

The device was patented in both Europe and the USA and went into production,8 though was hardly a success – perhaps 180 machines in total were produced. Those who did use were impressed, including, most notably, Friedrich Nietzsche. Struggling with failing eyesight received a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball in 1882 and was so enamoured that he penned a brief poem about it which began: “The writing ball is a thing like me: made of iron…”. Although a commercial failure, this thing made of iron was actually very practical. Contemporary accounts report experienced users reaching typing speeds of 160 words per minute. To put this in context the five-minute speed record on a “modern” mechanical typewriter is around 176 words per minute. I find it fascinating to wonder what might have happened if this design had ‘won’ and quite how laptops would look today as a result!

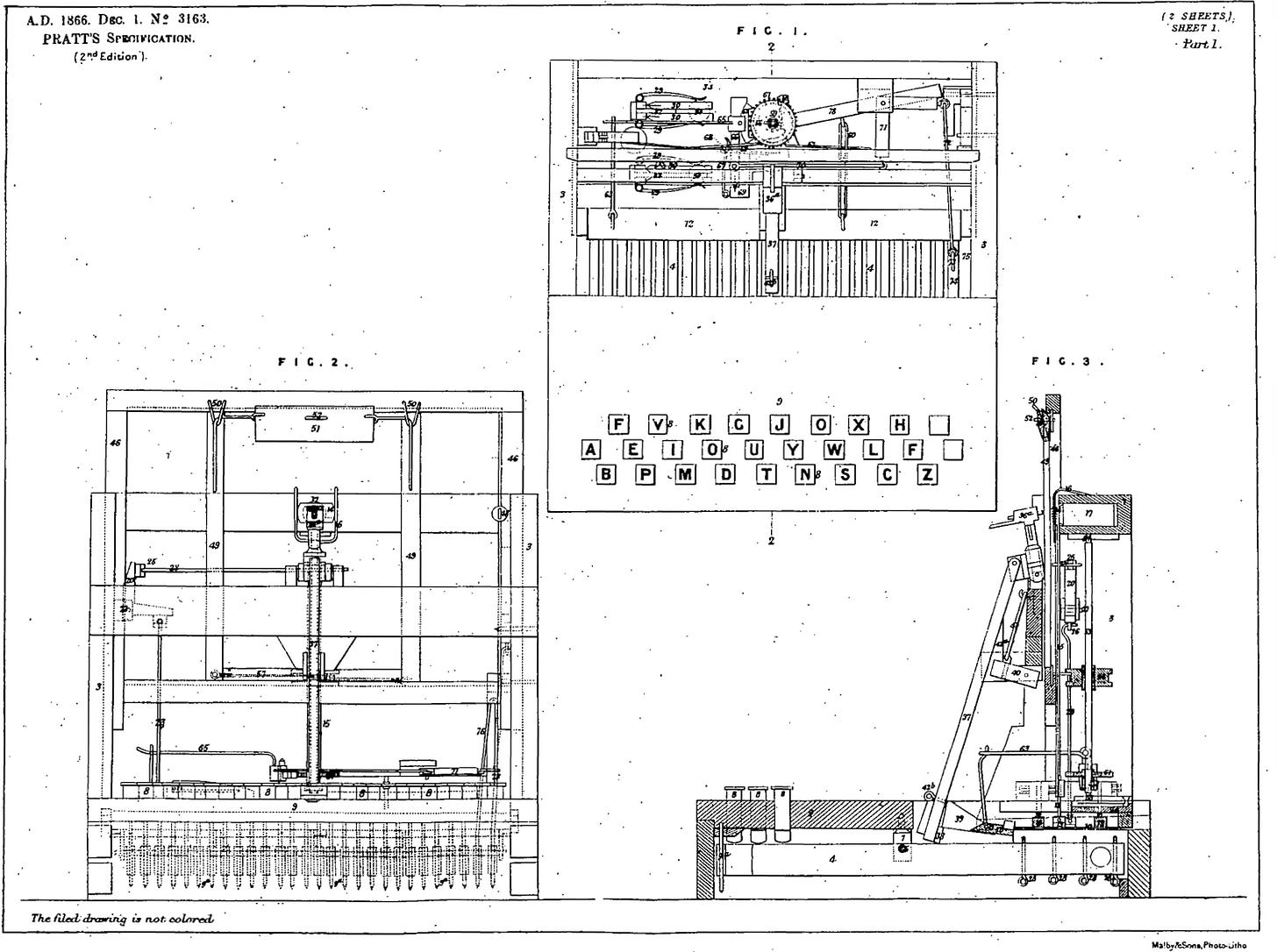

The last9 of the “nearly, but not quite” typewriters was the Pterotype, patented by the American John Pratt in London in 1866 and it took a very different approach from the other attempts. Instead of having letters on hammers Pratt used a metal “type plate” embossed with characters.10

The plate moved up/down and left/right to bring the chosen character to a single printing point; then a hammer struck the paper from behind and pressed it against the plate. In this respect it can be seen as something of a forerunner of IBM’s “typeball” (also known as the “golf ball”) introduced in 1961 in their Selectric electric typewriters (more on this next time). Pratt’s machine soon went into mass production and was sold widely around the globe. No, of course it didn’t, none were produced commercially, but the publicity surrounding his work did help to inspire those who, as we shall see in my next piece, created the machines that transformed the world.

In the unlikely event that anyone is interested in what I laughingly refer to as my “process” the document starts out as a place where I collate all of my research, quotes, and references. When it comes to beginning the writing proper, I have the document open in two windows, twin-screened. I start writing at the beginning of the document in the top window, and then scroll through the version of the document in the lower window to have the relevant research readily to hand.

As an aside, I found this piece fascinating to research. My (ignorant) assumption had been that there was probably an initial invention, which got iterated (and I had known something of the various keyboard arrangements). I would never have guessed that there had been so many different attempts and also-rans.

No, it is not a coincidence that her name, and that of the town in which she resided, were the same.

It may seem suspicious that so many of the early typewriters have been lost, but that it just history I am afraid.

Some sources say 32 keys.

If you have read this far then you will know that it is pretty clear that he wasn’t.

We know this detail from the writings of his daughter, Johanne Elisabeth Agerskov, who was a famous spiritualist and medium.

Finally one gets put into production!

Yes, I do realise that I have skipped over François Xavier Progin’s 1833 attempt which some argue was the first typewriter with individual moving keys. Or, indeed, the Brazilian Padre Francisco João de Azevedo who publicly exhibited a “máquina taquigráfica” in 1861 which, and you will be ahead of me here, I am sure, never went into production.

Do have a look at the letter arrangement on his keyboard!

Great piece of work Paul.

This was of interest to me, I was a typewriting teacher from the 1960s to the 1980s in Australian secondary schools. I am now waiting to read Part 2 of this fascinating history of the typewriter.