Gin and tonic is probably my favourite alcoholic drink and I have always been curious about how it came into being. It is probably easiest to explore the histories of gin and tonic separately, before looking at how they came to be combined.

Gin as we know it today evolved from the Dutch drink jenever, a spirit originally made from distilling malt wine. As stills at the time were crude by today’s standards the resulting output, at around 50% alcohol, was so rough that it was all but unpalatable. To counter this, herbs were added to the mix along with juniper, the key flavour of gins to this day. Initially however juniper was not added due to the flavour that it imparted, but rather to the perceived health benefits that it would imbue. It is in this context that we find the first reference to distilling with juniper in Der naturen bloeme (The Flower of Nature) a 1266 text written by the Flemish poet Jacob van Maerlant. This is something of a natural history guide and something of a bestiary, though it is fair to say that some of the animals pictured veer into the fantastical!

In it he writes:

He who wants to be rid of stomach pain

Should use juniper cooked in rain.

He who has cramps

Cook juniper in wine,

It’s good against the pain

It may seem a little assumptive to say that he is talking about distilling here, but many scholars believe that he is describing a gin-like drink. It wasn’t long before this tasty and potent product began being drunk for recreational, rather than medicinal, purposes. The first known recipe for jenever can be found in the 1552 book Een Constelijck Distileerboec1 (A “something”2 distillation book) by Philippus Hermanni, who included depictions of the stills of the time.

It wasn’t long after that the English first encountered it during the Eighty Years’ War (c.1568–1648). The English struggled with the word jenever and anglicised it – first to genever and thence to giniver (you can probably see where this is going). By this time jenever was being distilled from barley, rather than wine, and often aged in oak barrels so despite its juniper flavouring it had some of the characteristics of modern whisky.

It is somewhere around this time (I have seen dates ranging from 1585 to the 1660s suggested, with the English fighting either alongside, or against, the Dutch) that the phrase ‘Dutch courage’ (meaning the boost one got from an alcoholic drink before going into battle) came into existence. There are conflicting stories about who was doing this beneficial pre-conflict drinking. Some say that it was the English soldiers, fortifying themselves on the local hooch, while others say that it was the Dutch, taking nips from flasks they carried with them onto the battlefield.

Jenever was widely drunk in the Netherlands in the second half of the 17th century, but it wasn’t much consumed in England until the Glorious Revolution of 1688 which installed William of Orange, and his wife Queen Mary, on the British throne. There were a couple of reasons why this led to gin becoming the most popular drink in the country. The first is that people were keen to support their king by emulating his Dutch ways, so much so that gin was referred to as the ‘Protestant drink’. The second (and more significant) was due to economics. The ongoing conflict with France led to a series of increases on the tax on imported brandy over the course of the 1690s. At the same time measures were introduced to make it much easier to distil and sell British gin produced from locally grown corn. Distillers were not required to be licensed, and taxes on gin were reduced while simultaneously being increased on beer and ale.

Unsurprisingly, brandy sales collapsed, and those of gin went through the roof. Daniel Defoe writing in 1727 observed:

The Distillers have found out a way to hit the palate of the Poor, by their new fashion’d compound Waters called Geneva, so that the common People seem not to value the French-brandy as usual, and even not to desire it.

And hit the palate of the poor it did, for this was a drink that could get you “drunk for a penny, dead drunk for two”. The resulting gin craze that lasted for the first half of the 18th century is difficult to fully appreciate now, but I’ll try and set the scene. London, with a population of 630,000 people had (depending upon which source you believe) between 7,500 and 17,000 gin shops or between one for every 60 adults or one for every 30. One source claims that the average Londoner (every man, woman, and child) was at one point drinking two pints (1.1 litres) of gin each a week – or four double shots a day.

This popularity wasn’t due to the drink’s refined character. It was a rough fire-water, closer today to the Irish poitín (poteen) than modern gin. It was also very strong, probably around 80% alcohol, double the strength we are used to (so those four double shots would have been 16 units of alcohol). Worse, to make it taste better things were added to it, chief among these being turpentine (yup, the stuff used to clean paintbrushes) which is, of course, poisonous.

The fact that a significant part of the urban population was more or less constantly inebriated did not not go unnoticed, and caused a moral panic among the great and good of society. As early as 1721 the Middlesex magistrate was citing gin as “the principal cause of all the vice & debauchery committed among the inferior sort of people” and in 1736 reported:

It is with the deepest concern your committee observe the strong Inclination of the inferior Sort of People to these destructive Liquors, and how surprisingly this Infection has spread within these few Years… it is scarce possible for Persons in low Life to go anywhere or to be anywhere, without being drawn in to taste, and, by Degrees, to like and approve of this pernicious Liquor.

Such statements were not simply hyperbole, as the tragic case of Mary Defour demonstrates. Mary’s mother, Judith Defour, was a ‘throwster’ (someone who twisted silk threads into yarn) who, unable to care for her two-year-old daughter, had her placed in a workhouse. On 29 January 1733 she went to the workhouse and asked to take her daughter out for a couple of hours. She was told that she needed a note from a churchwarden giving her permission, and so she returned a little later with one (which later turned out to have been faked). Mary was duly handed over to her but was never seen alive again – she was found dead in a ditch the following day. Judith’s later confession explains what happened:

On Sunday Night we took the Child into the Fields, and stripp’d it, and ty’d a Linen Handkerchief hard about its Neck to keep it from crying, and then laid it in a Ditch. And after thay, we went together, and sold the Coat and Stay for a Shilling, and the Petticoat and Stockings for a Groat. We parted the Money, and join’d for a Quartern of Gin.

A mother killing her own child in order to buy gin was almost beyond belief: something had to be done! Alas not for the first (or indeed last) time in history the steps taken by those in power had unintended consequences…

The Spirit Duties Act 1735 (better known as the Gin Act 1736) levied a duty of 20 shillings (one pound) on every gallon of gin and required every business selling gin to purchase a licence for £50. Simultaneously a reward of £5 was offered to anyone who reported an establishment illegally selling gin. Ascribing modern values to historic sums of money is a tricky business, but to put it in context, a labourer was earning perhaps £10 a year, so this was a vast sum. The intention was that these rewards would be funded through the income accrued from the duties and licences, but things didn’t work out like that. Only two annual licences were ever sold (and remember there were at least 7,000 gin shops in London at the time). Fortunes were paid out to informants, with no income to cover these costs. Much like prohibition in the USA it turned gin-selling into an illegal business. After an initial dip when the act first came into force gin consumption soon returned to, then exceeded, the levels that it had been before. Criminal gangs were making fortunes and critically the product being sold became even more toxically adulterated.

There were however some entertaining characters involved in the trade, most notably one Dudley Bradstreet. A picaresque figure, he went on to be a government spy during the Jacobite rising, most notably persuading Charles Stuart’s army to retreat to Scotland by claiming that an army of 9,000 men was waiting for them in Northumberland (it simply didn’t exist). His ingenious response to the new law was to, err, sell gin via cats!3

The Mob being very noisy and clamorous for want of their beloved Liquor, which few or none at last dared to sell, it soon occurred to me to venture upon that Trade. I bought the Act, and read it over several times, and found no Authority by it to break open Doors, and the Informer much know the Name of the Person who rented the House it was sold in. To evade this, I got an Acquaintance to take a House in Blue Anchor Alley in St Luke’s Parish, who privately convey’d his Bargain to me; I then got it well secured… and purchased in Moorfields the Sign of a Cat, and had it nailed to a Street Window; I then caused a Leaden Pipe, the small End about an Inch, to be placed under the Paw of the Cat the End that was within had a Funnel to it.

I got a Person to inform a few of the Mob, that Gin would be sold by the Cat at my Window the next Day, and provided they put the Money in its Mouth from whence there was a hole that conveyed it to me… it was near three Hours before any body called… at last I heard the Chink of Money, and a comfortable Voice say, “Puss, give me two Pennyworth of Gin.” I instantly put my Mouth to the Tube, and bid them receive it from the Pipe under her Paw, and then measured and pour it into the Funnel from whence they received it.

This approach was soon widely copied in what became known as “Puss and Mew” shops, as the customer had to address the cat as “puss” and if gin was available the hidden seller would mew in response!

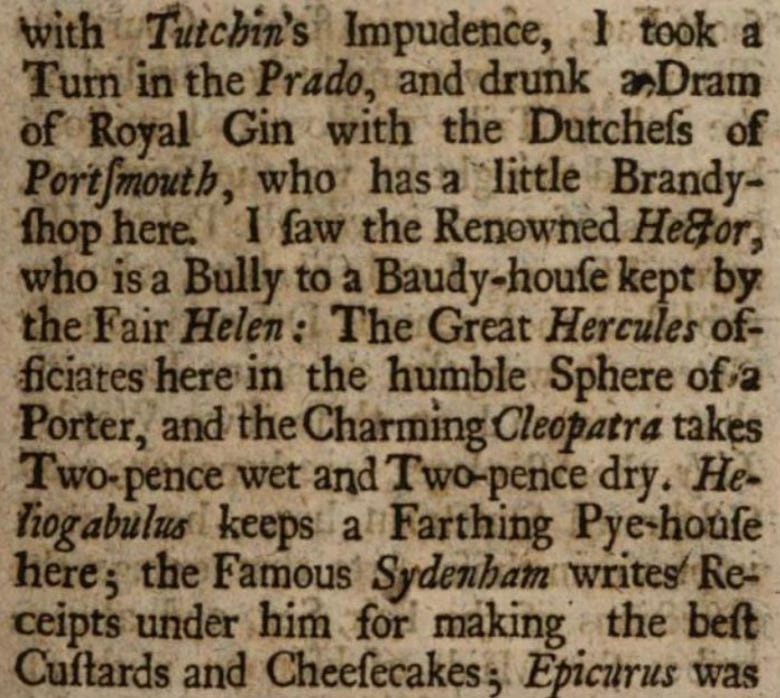

And it is here that Part 1 ends, with London awash with cat-dispensed gin, society in chaos, and Parliament just making things worse. In the next instalment we will learn how the gin craze finally ended, how it became elevated into the refined drink of today, and how tonic water became part of the mix. I’ll leave you now with the first recorded use of the word ‘gin’ in the English language, written by the actor Richard Estcourt in around 1712.

Or to give it it’s full title: Een constelijck distileerboec inhoudēde de rechte en̄ waerachtige conste der distilatiē om alderhande waterē der cruydē, bloemen, en̄ wortelen en̄ voorts alle ander dingen te leeren distileren opt alder constelijcste, also dat die ghelijcke noyt en is gheprint geweest in geenderley sprake (A constellic distillation book contained the straight and true method of distillation in order to learn to distill all kinds of water, the cruid, flowers, and roots, and furthermore, all other things in every constitutive manner, even if it is not and has not been printed in any way). Which is a bit of a mouthful.

I can’t work out what Constelijck means

Gins with black cat logos, including Old Tom, are still sold today in a nod to this practice.

My 7th great uncle was John Debonnaire, 1696-1747 who part-owned the distillery on 3 Mills Island.

His Huguenot family had escaped to England after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Sylvia Wright