A history of… taxis (Part 2)

18th-century cab passengers had to be on guard against wig-snatchers

In my last post I described the history of the taxi up to the invention of the cabriolet in France at the start of the 18th century. This was a small, light carriage that was pulled by a single horse and could accommodate two passengers covered by a leather hood on a moveable frame. Due to a combination of cheapness and speed – they could cut through the streets far more nimbly than the significantly larger hackney carriages – they soon became incredibly popular and spread to other European cities.

These ‘cabs’ were not without their downsides, however. Phone-snatching, often carried out by criminals on e-bikes, is a scourge of modern London but something similar was also taking place in the 18th century as this entry from the Weekly Journal dated March 30th 1717 describes:

The Thieves have got such a villainous way now of robbing gentlemen, that they cut holes through the backs of Hackney coaches,1 and take away their wigs, or fine head-dresses of gentlewomen; so a gentleman was served last Sunday in Tooley-street, and another but last Tuesday in Fenchurch-street; wherefore, this may serve for a caution to gentlemen or gentlewomen that ride single in the night-time, to sit on the fore-seat, which will prevent that way of robbing.

The next major development in taxi evolution came at the hands of one Joseph Hansom, an architect from Yorkshire who, in 1834, invented the Hansom cab.2 Like the French cabriolets, these were vehicles for two people, pulled by a single horse; however they had a number of significant differences. The driver sat on a sprung seat at the back of the carriage, raised so that he could control the horse (and see where he was going) over the roof of the structure. Low-slung body work and high wheels gave the cab a low centre of gravity, which enabled safe cornering and overtaking, and two curved fenders prevented stones being thrown up into the passenger cabin from the horse’s hooves.

The low cab and large wheels could make getting in and out of the cab somewhat challenging, as Charles Dickens humorously described in his Sketches by Boz:

Some people object to the exertion of getting into cabs, and others object to the difficulty of getting out of them; we think both these are objections which take their rise in perverse and ill-conditioned minds. The getting into a cab is a very pretty and graceful process, which, when well performed, is essentially melodramatic. First, there is the expressive pantomime of every one of the eighteen cabmen on the stand, the moment you raise your eyes from the ground. Then there is your own pantomime in reply—quite a little ballet. Four cabs immediately leave the stand, for your especial accommodation; and the evolutions of the animals who draw them, are beautiful in the extreme, as they grate the wheels of the cabs against the curb-stones, and sport playfully in the kennel. You single out a particular cab, and dart swiftly towards it. One bound, and you are on the first step; turn your body lightly round to the right, and you are on the second; bend gracefully beneath the reins, working round to the left at the same time, and you are in the cab. There is no difficulty in finding a seat: the apron knocks you comfortably into it at once, and off you go.

The getting out of a cab is, perhaps, rather more complicated in its theory, and a shade more difficult in its execution. We have studied the subject a great deal, and we think the best way is, to throw yourself out, and trust to chance for alighting on your feet. If you make the driver alight first, and then throw yourself upon him, you will find that he breaks your fall materially. In the event of your contemplating an offer of eightpence, on no account make the tender, or show the money, until you are safely on the pavement. It is very bad policy attempting to save the fourpence. You are very much in the power of a cabman, and he considers it a kind of fee not to do you any wilful damage. Any instruction, however, in the art of getting out of a cab, is wholly unnecessary if you are going any distance, because the probability is, that you will be shot lightly out before you have completed the third mile.

As you may have gleaned from the above passage, an attractive feature of these new cabs was their price. A London magazine in 1842 noted that a cabriolet could be hired for as little as one shilling – within reach of the burgeoning middle class. For the first time, catching a cab wasn’t just a luxury for aristocrats; clerks, lawyers and visitors on errands could all ‘take a cab’ when speed or weather demanded. London and Paris led the way in formalizing cab services. Both cities required cab drivers to be licensed and numbered. Paris had its fiacre licences; London capped the number of cab licences (a carryover from hackney coach limits). Guidebooks from the mid-1800s list cab stands at railway stations, hotels and main thoroughfares, and newspapers regularly reported on cab fares and misadventures. In Paris, satirists and songwriters referenced fiacre drivers in popular culture – sometimes as rough-hewn but essential service providers. An 1848 Paris guide dryly noted that fiacre drivers, while prone to fleecing unwary tourists, “chaque jour rendent de grands services” (each day render great services). Though in time they would face competition from motorised alternatives, these cabs proved remarkably persistent – the last licence for a horse-drawn cab in London was issued in 1947.

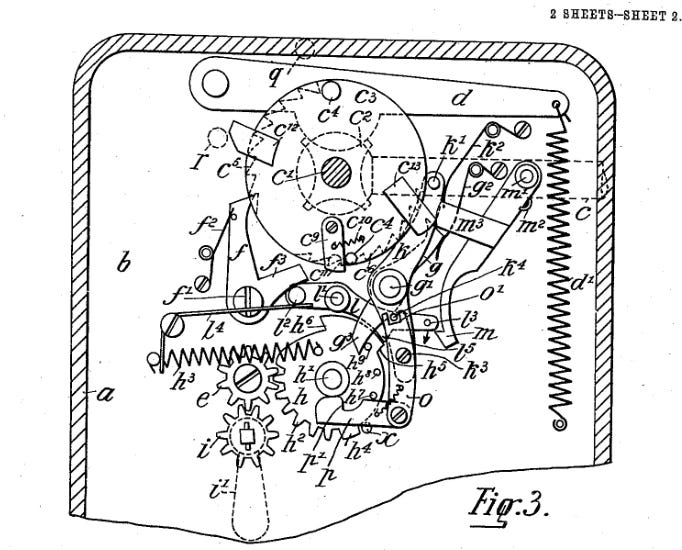

The development that turned the simple cab into the taxi-cab came about as a solution to an obvious and all-too prevalent problem – how do you know if your cabman has charged you the correct fare or if he is trying to scam you? The answer to this was the taximeter – a device to automatically calculate fares based on distance (and time) – which was invented in 1891 by a German engineer, Friedrich Wilhelm Gustav Bruhnin. These devices were really very ingenious. When the passenger got in, but the cab wasn’t moving, a clockwork mechanism started which increased the fare based upon the time the vehicle was stationary. When the cab was moving a distance drive was taken by a flexible shaft from a front wheel, which increased the charge while rolling. The device automatically used whichever input was ‘on top’ at the moment: when the cab stood still the clockwork advanced the fare; once it moved, the wheel drive overran the clockwork and took over. As a report at the time explained:

The taximeters are circular instruments about the size of street-car fare registers. Unlike the latter, however, they are autotic in action, calculating and indicating at all stages of the trip the precise amount of fare the customer has to pay, thereby eliminating any possibility of the driver making excessive charges, and pocketing a part of the receipts for himself.

The English word taximeter comes via the French taximètre, adapted from German Taxameter. The German coinage combines medieval Latin taxa (charge, tariff) and meter (measure, from Greek métron). The first use of ‘taxameter’ in English occurred in The Times in 1894 and this had evolved to taximeter by 1898–9. The words taxi and taxicab were first seen in 1907 and have persisted to this day, though London black cabs are still formally referred to as ‘hackney carriages’, harking back to the days of the horse-drawn cabs.

Around the same time inventors were experimenting with horseless carriages for hire. In the 1890s, both electric and gasoline-powered vehicles appeared as potential cabs. One of the earliest was the Daimler Victoria, built by Gottlieb Daimler in 1897, a gasoline automobile equipped with a taximeter and delivered to Friedrich Greiner, who started the world’s first motor taxi company in Stuttgart. That same year in London, Walter Bersey introduced electric battery-powered cabs (nicknamed Hummingbirds for the noise they made) though they turned out to be a short-lived experiment due to the challenges of maintaining them – yes, there were all-electric cabs operating in London in the 19th century!

By 1899, Paris saw its first gasoline taxis (all French-made vehicles), and by 1903 the trend reached London in earnest, with motor cabs gradually replacing horse-drawn hansoms. These early motor taxis often used the latest French cars – in fact, many of New York’s first gasoline cabs were imported French Darracq or Renault. Paris embraced motorized ‘autotaxis’ quickly. A notable fleet, the Compagnie Française des Automobiles de Place, put scores of Renault motor cabs (with taximeters) on Parisian streets in the early 1900s. By 1907, Paris had thousands of motor taxis, which famously would play a role in 1914 ferrying soldiers to the Battle of the Marne.3 London’s motor cabs, often called just ‘taxis’ to distinguish them from the remaining horse-cabs, gained popularity after 1906 when reliable models like the Prunel and Unic came into service. In 1907, London mandated that all new cabs must have taximeters, a move initially resisted by drivers used to negotiating fares.

Across the Atlantic, New York City lagged slightly but caught up dramatically around 1907. That year, a 30-year-old businessman named Harry N. Allen became a catalyst. After being overcharged by a Manhattan hansom cabbie, Allen vowed to start a better cab service. He imported 65 gasoline-powered French cabs (painted red and green) fitted with taximeters and launched New York’s first meter-equipped taxi fleet in mid-1907. As contemporary reports noted, “In 1907, [Allen] imported his vehicles with their taximeters from France to New York. He had the first metered cabs in the city.” The novelty of the precise fare and the speed of motor cars attracted curiosity and ridership in equal measure. However, Allen’s innovation met with pushback from the established drivers of horse-drawn cabs. Used to setting their own prices (and often receiving generous tips), many cabbies saw meters and employee status as a threat to their income. By mid-1908, Allen’s drivers were in open revolt over pay, and a strike turned violent. One period source recounts that “just a year later his drivers staged a walkout over their pay” – in fact, New York’s first taxi strike (and riot) occurred in August 1908. Striking cabbies attacked the shiny new motor taxis; several vehicles were smashed and tipped over in the streets of Manhattan and police intervention was needed to restore order. This violence was ultimately futile; the rise of the mechanised, metered cab proved to be unstoppable.

By the 1910s, every major metropolis had its fleet of taxicabs. They were often painted in distinctive liveries: London’s were initially green or red, but soon black became standard (giving us the London ‘black cab’). Paris taxis were famously red or green; New York’s early fleets were various colors – red-and-green, or yellow, or chequered. An arms race of sorts began in branding as the different companies competed for fares and this ultimately resulted in the NYC cabs that we know of today. In 1910, a New York cab company owner painted his taxis canary yellow based on a university study that found yellow most visible from a distance. Soon, yellow cabs spread to Chicago and beyond, thanks in part to businessman John Hertz,4 whose Yellow Cab Co. (founded 1915) became one of the largest taxi operators in America.

A few years later in New York, during the Great Depression, vast numbers of ‘wildcat’ cabs (unlicensed operators that undercut official fare rates to poach customers) flooded the streets which caused the wages of the official cab drivers to collapse. To address this, in 1937 the Board of Aldermen passed the Haas Act, which created a medallion system and capping the number of taxi licences at 13,595 (later falling by attrition to ~11,787 active by the 1940s). Licences cost $10 to renew; and only cabs with a medallion were able to ply their trade on the streets of the city. For decades the cap barely budged. New sales were rare until the late 1990s and 2000s, when the state and city authorized limited waves: e.g., up to 900 new medallions authorized in 2003 leading to big auctions in 2004 (nearly 600 sold that year; plan to lift the fleet from 12,187 to 13,087), then further sales in 2006, and a wheelchair-accessible tranche in 2013–2014. This forced scarcity of permission to operate in a highly lucrative trade made these medallions incredibly valuable. By 2003 they traded at over $300,000 apiece, but reached their highest peak in 2013–14 when they were selling for over one million dollars each.

This peak did not last for long. The growth of ride-hail apps in the years that followed caused the prices to crash and they now trade for between $90k–$200k. In London however, there is no formal limit on the number of black cabs, but their numbers are restricted by the fact that to be able to drive one you have to pass arguably the toughest examination in the world, The Knowledge. For the full ‘All London’ licence (the ‘green badge’), candidates must memorise every viable route, traffic restriction, and more than 6,000 landmarks within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross, the traditional centre of London. The core syllabus is a set of 320 exemplar routes (‘runs’) published in Transport for London’s Blue Book; they also learn the ¼-mile catchment around the start and end of every run so the drivers pick up the local street web and the places people actually ask for (‘points’). This means that in order to pass, prospective drivers have to memorise more than 25,000 streets, a challenge which takes most candidates three or four years.

This astonishing feat of memory actually changes the brains of the cab drivers who complete it. A famous University College London study by Professor Eleanor A. Maguire showed that licensed London taxi drivers have larger posterior hippocampi (a brain area critical for spatial memory) than controls, with the size increase correlating to years of their experience. The Knowledge has been a requirement for London cab drivers since 1865, and although the number of people passing it has declined in recent years (in part due to the rise of Uber and other apps) I hope that this astonishing tradition will continue for many years to come.

I realise that this says hackney carriages, not cabriolets, but I think it had to be the latter. The carriages had solid wooden backs, as opposed to leather which could be cut through. It also advises to “sit on the fore-seat” which makes sense in the two-seat cabriolet which had one in front of the other.

Thought it was soon afterwards modified, and improved, by John Champman.

It would seem, however, that the impact of this their action in this regard was somewhat exaggerated at the time.

The taxi wars of this era were brutal. Hertz sold his remaining stake in the Yellow Cab Co. after his stables were firebombed in 1928 and 11 of his horses were killed.

Great pair of articles, fascinating stuff. The origin of the word ‘taxi’ had somehow passed me by, so thanks for curing me of that particular ignorance!

The contribution to the Battle of Marne was hyped up for propaganda purposes. The French civilians in support of the war effort.