Making a craft that can travel across the surface of a body of water is a fairly straightforward thing to do, and has been done countless times across human history. Creating something that can travel under the water, that’s a bit more tricky. It turns out, though, that people have been doing it – with varying degrees of success – far longer than you might expect. This week I’ll be exploring the history of the submarine.

Some sources claim that the first submarine can be traced back to Alexander the Great who, in 332 BCE, went down into the sea in a glass-windowed barrel so that he could study the fish. There are a couple of problems with this – firstly, this describes a diving bell, and not a submarine; secondly it never happened!1 It appears in versions of the Alexander Romance, a collection of wildly embellished stories published more than half a millennium after he died.

Some 1,800 years later we have none other than Leonardo da Vinci (1492–1519) exploring a similar idea, with an illustration in the Codex Atlanticus showing a man in a leather diving suit being fed air through tubes on the surface. Okay, so it still isn’t a submarine, but in one of his notebooks Leonardo made a tantalising reference to an underwater vessel that he had designed:

How by means of a certain machine many persons may stay some time under water. How and why I do not describe my method of remaining under water, or how long I can stay without eating; and I do not publish nor divulge these on account of the evil nature of men, who would practice assassinations at the bottom of the seas, by breaking the ships in their lowest parts and sinking them together with the crews who are in them.

The great inventor was very prescient in his concerns, because the desire to have something capable of “breaking the ships in their lowest parts” was precisely what drove the development of underwater craft in the years that followed. A century later William Bourne (c.1535–c.1582), a naval gunner and self-taught inventor, wrote in Inventions or Devises (1578):

It is possible to make a ship or boat that may go under the water unto the bottome, and so to come up againe, and whych thinge may be practised without danger of any man's lyfe, that shall travayle in the same, for he may make it to sinke and rise as he listeth

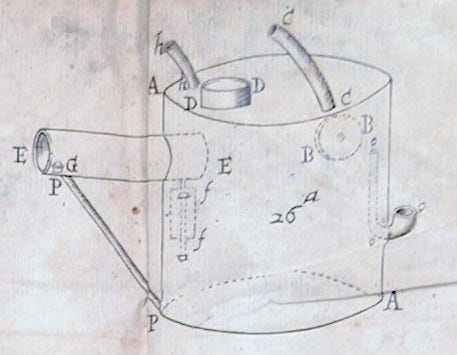

In his (unbuilt) design the sealed craft would have leather ballast bladders inside that opened out into the water. By crushing the bladders with screw presses water would be forced out, reducing the mass of the craft, causing it to rise. It is only a few decades later that we hear of the demonstration of the first true submarine. Cornelius Drebbel (1572–1633) was a Dutch inventor, engineer and alchemist who, after settling in England in 1604, fell under the patronage of King James I (1566–1625). We know frustratingly little about the exact nature of his submarine, but there are numerous sources that attest to its existence. A Dutch writer, C. van der Woude, wrote of Drebbel in 1645:

He built a ship in which one could row and navigate under water, from Westminster to Greenwich, the distance of two Dutch miles,2 even five or six miles, or as far as one pleased. In the boat a person could see under the surface of the water and without candle light as much as he needed to read in the Bible or any other book. Not long ago this remarkable ship was yet to be seen lying in the Thames or London river.

Writing a few years later, in 1660, the scientist Robert Boyle also confirmed this story:

[Drebbel]… is affirmed by more than a few credible persons to have contrived for the late learned King James, a vessel to go under water, of which tryal was made in the Thames with admired success, the vessel carrying twelve rowers besides passengers, one of which is yet alive, and related it to an excellent mathematician that informed me of it.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the discoverer of ‘Boyle’s Law’ (which states that the pressure of a gas is inversely proportional to its volume, provided the temperature and amount of gas remain constant) was particularly curious about how the rowers were able to keep breathing:

Now that for which I mention this story is, that having had the curiosity and opportunity to make particular enquiries among the relations of Drebbel and especially of an ingenius Physician that marry’d his daughter concerning the grounds upon which he conceived it feasible to make men unaccustomed to continue so long under water without suffocation, or (as the lastly mentioned person that went in the vessel affirms) without inconvenience, I was answered that Drebbel conceived, that ’tis not the whole body of the Air, but a certain Quintessence (as Chymists speak) or spirituous part of it, that makes it fit for respiration, which being spent, the remaining grosser body or Carcase (if I may so call it) of the Air, is unable to cherish the vital flame residing in the heart.

Fascinatingly, it seems that in trying to work out how to survive underwater Drebbel divined the existence of oxygen, which was formally discovered more than a century later by Joseph Priestley in 1774.3 It appears, incredible though it may seem, that Drebbel, an alchemist himself, had somehow discovered a way to both generate oxygen and scrub carbon dioxide out of the air in the 17th century. The answer as to how he did this may lie in Drebbel’s book On the Nature of the Elements (1604) where he describes what happens when saltpetre is heated:

Very dry, subtle or warm air, which then very quickly penetrates the coarse, heavy clouds, expands them, makes them subtle and thin, and again changes them into the nature of air, whereby its volume is increased an hundredfold in a moment, which brings forth the terrific motion which, cracking and bursting, sets the air alight and moves it, until volume and density are equal, when there is rest.4

What we can be sure of is that the “ingenius Physician” was Johannes Siberius Kuffler, who had indeed married Drebbel’s daughter and attempted to capitalise on his father-in-law’s work, as Samuel Pepys, who was Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board, recorded in his diary entry for 14th March 1662:

In the afternoon came the German Dr. Kuffler, to discourse with us about his engine to blow up ships. We doubted not the matter of fact, it being tried in Cromwell’s time, but the safety of carrying them in ships; but he do tell us, that when he comes to tell the King his secret (for none but the Kings, successively, and their heirs must know it), it will appear to be of no danger at all.5

It might seem like Kuffler was just a chancer, but he was willing prove his claims, as the Calendar of State Papers, Domestic 1661–62 records:

Request of Johannes Siberius Kuffler and Jacob Drebble [sic] for a trial of their father Cornelius Drebble’s secret of sinking or destroying ships in a moment; and if it succeed, for a reward of 10,000l. The secret was left them by will, to preserve for the English crown before any other state.

The sum requested, tens of million of pounds in today’s money, was far too rich for the King to consider so it would seem that this secret, if it actually did exist, has been lost to history for ever.

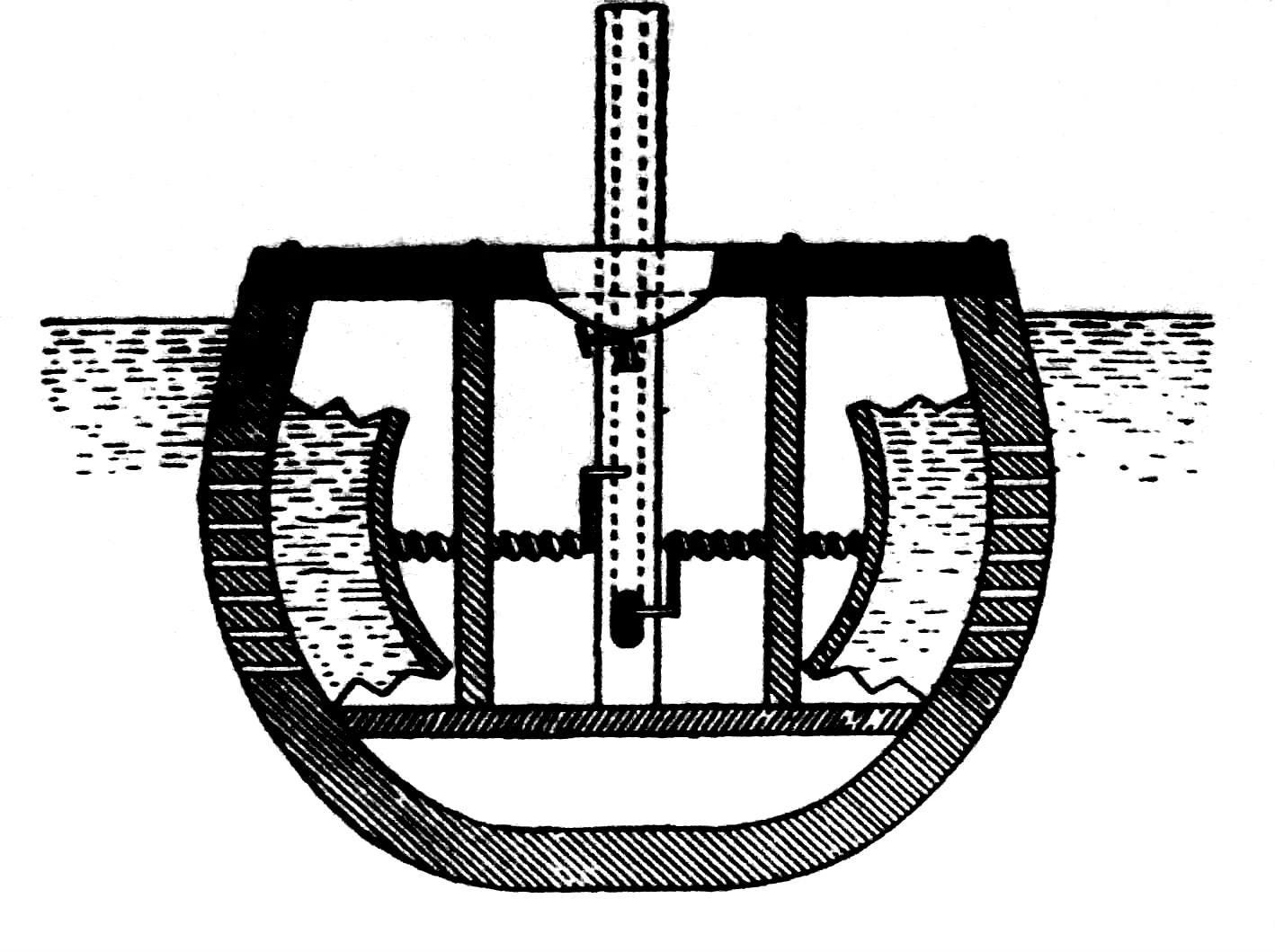

Towards the end of the 17th century we have a kind of submarine for which a design still exists. Denis Papin (1647–1713) was a French inventor and engineer who had a particular interest in the power of compressed air and steam – his ‘steam digester’ was a very early pressure cooker. His first attempt at an underwater craft in 1690 was very much a proof of concept – a large reinforced metal cube that used air pumps to maintain pressure and had both water and external physical ballast. Sadly for Papin it was so heavy that the crane lowering it into the water for its first test collapsed and the craft was destroyed.

Undeterred, he then developed ‘The Urinator’,6 which launched in 1692. This was a proper, functioning submarine, with ballast control, pumps providing air through a hose attached to a floating bladder on the surface, and a manually operated screw propeller (the first time a screw propeller was used on a vessel of any kind). However there is no robust evidence that Papin ever got beyond testing the concepts and a prototype.

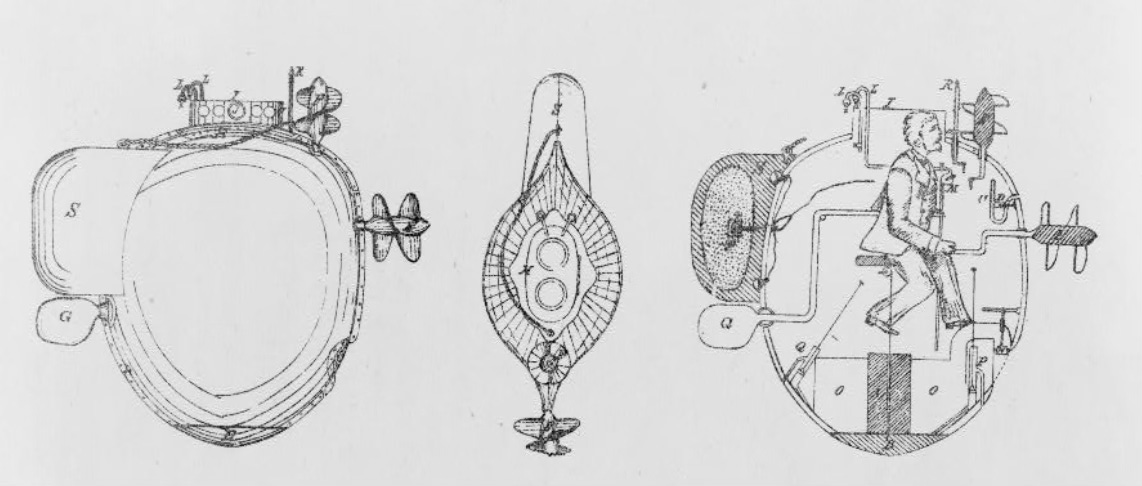

Very little progress was made in the decades that followed, until we reach David Bushnell (1740–c.1824) and the American Revolutionary war. His submarine, the Turtle, was a single-person craft, powered by a hand-cranked propeller and armed with a ‘torpedo’ – though this wasn’t what we would think of as one; rather it was a clockwork-timed explosive device designed to be screwed into the hull of the enemy ship. A letter Bushnell sent to Thomas Jefferson on 13th October 1787 explains how it got its name:

The external shape of the sub-marine vessel bore some resemblance to two upper tortoise shells of equal size, joined together; the place of entrance into the vessel being represented by the opening made by the swell of the shells, at the head of the animal.

This craft was not only built but used in actual combat, in an attack on the HMS Eagle on 7th September 1776. The sub reached its target but, alas, failed to screw its torpedo into the Eagle’s hull as it was covered in copper plating. Except (you might be starting to see a trend here) this almost certainly never happened7 and was simply a propaganda story, as this letter from George Washington to Thomas Jefferson on 26th September 1785 proves:

Bushnel [sic] is a Man of great Mechanical powers—fertile of invention—and a master in execution—He came to me in 1776 recommended by Governor Trumbull (now dead) and other respectable characters who were proselites to his plan. Although I wanted faith myself, I furnished him with money, and other aids to carry it into execution. He laboured for sometime ineffectually, & though the advocates for his scheme continued sanguine he never did succeed. One accident or another was always intervening. I then thought, and still think, that it was an effort of genius…

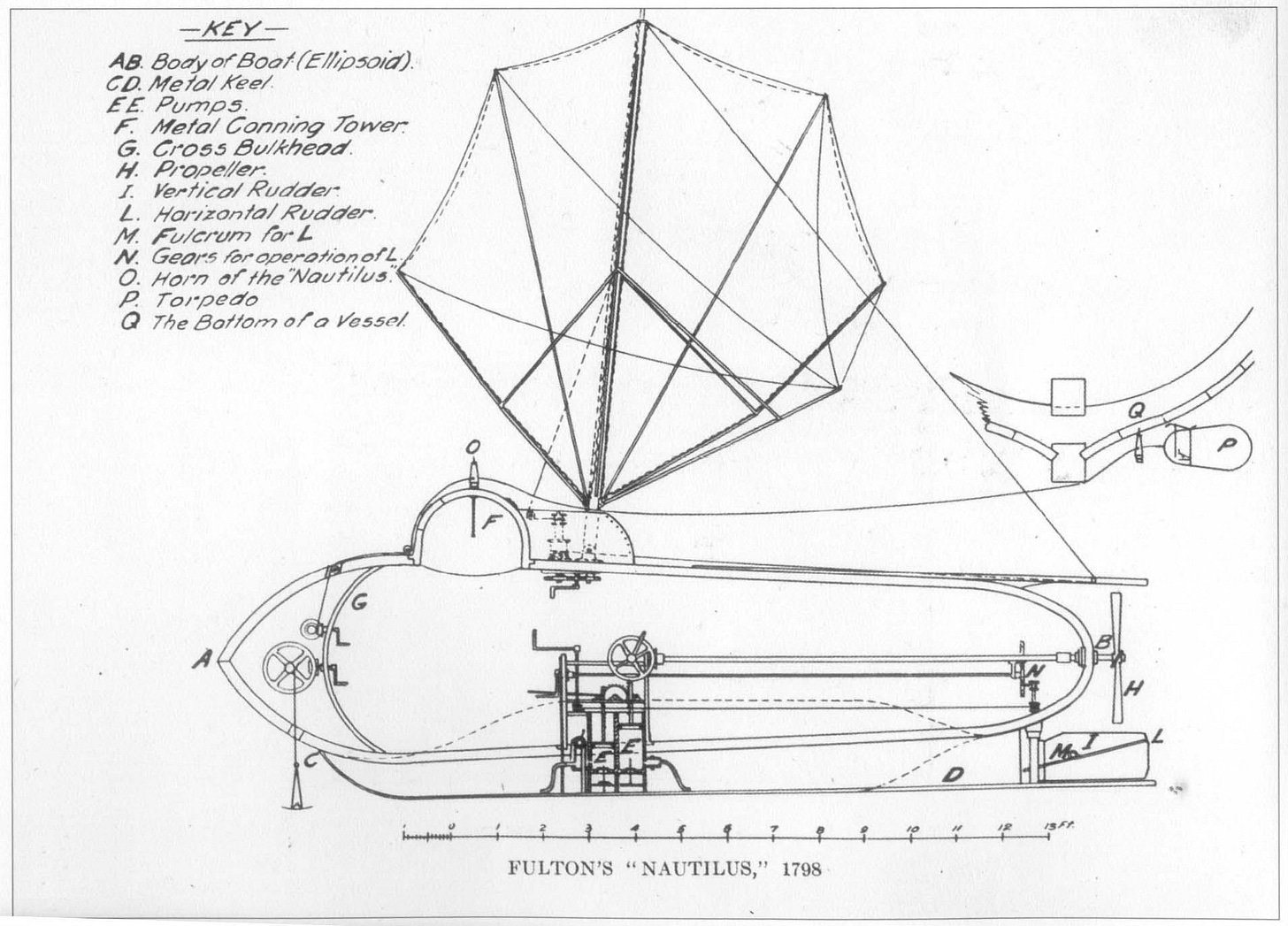

Finally, in 1800, we get an honest-to-god working submarine, the Nautilus built for the Napoleon Bonaparte by the American Robert Fulton (1765–1815).8 Some 6.5 metres (21 feet) long it was powered by a hand-cranked screw propeller (and had sails to use when on the surface). It successfully ran under water for 17 minutes and destroyed a 40-foot sloop in a trial by attaching a gunpowder-filled copper mine to it.

Napoleon was, however, not hugely impressed and his naval commanders were dubious about investing a vessel that could readily sink, killing its crew. Fulton approached the British, but they similarly were not overly enthusiastic about the idea. The worries of the French navy seem to have been well placed. In 1851 the Brandtaucher (‘Fire-diver’) designed by Bavarian engineer Wilhelm Bauer sank during trials (the crew luckily escaped).

Similarly the H. L. Hunley, a Confederate submarine deployed during the American Civil War, managed to kill a total of 21 crew (including its inventor, Horace Lawson Hunley) in three sinkings across its brief career. It was, however the first submarine to successfully sink a warship, the USS Housatonic on 17th February 1864. The Ictíneo II developed by the Spanish engineer Narcís Monturiol (1819–1885) was much more successful. Driven by a steam engine powered by a peroxide chemical reaction it ran under water for 7.5 hours in 1867. It was, however, wildly expensive, costing as much as two frigates, so the project was eventually scrapped.

The latter half of the 19th century is littered with numerous nearly successful submarines, but I’ll end with what is generally considered to be the first truly effective submarine, the Holland VI. John Philip Holland (1841–1914) was an Irish marine engineer who started working on submarine designs in earnest while laid up in hospital having broken his leg slipping on ice in Boston shortly after arriving in the USA in 1873. He submitted his initial designs to the US Navy in 1875, but they rejected them as unworkable. He then got funding from the Fenian Brotherhood (American-Irish revolutionaries, for use against the British). This led to the successful launching of the Fenian Ram 1881, but Holland fell out with the Fenians not long afterwards in a dispute about payment.9

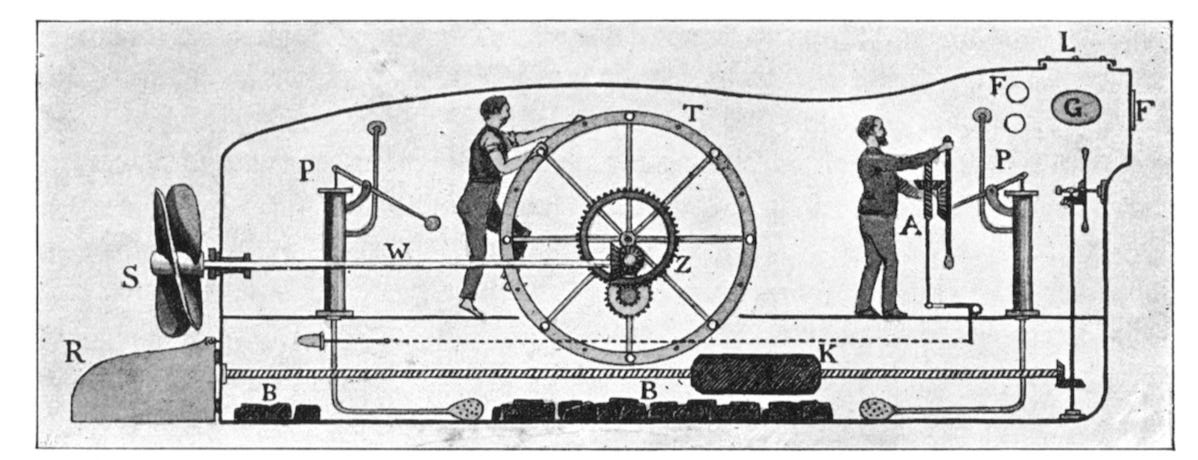

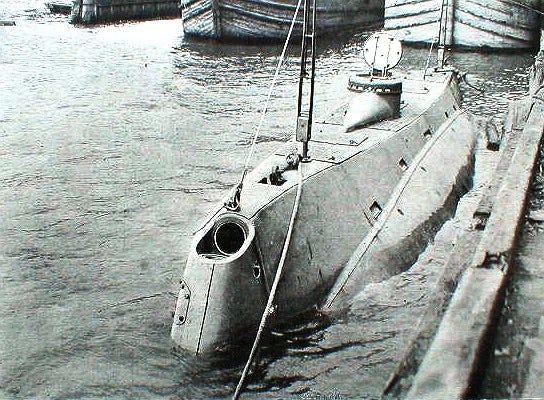

Holland continued his work, founding the Holland Torpedo Boat Company in 1896 and launching the Holland VI in 1897. This submarine had a conning tower, a torpedo tube, a petrol (gasoline) engine for running on the surface and charging batteries, and an electric engine for running under the water. With a crew of six she could dive to 23 metres (75 feet) and run for 30 nautical miles (55.6 km) under water (200 nautical miles on the surface).

She was commissioned into the US Navy as their first submarine, the USS Holland (SS-1). This design was to provide the basis of a total of seven subs provided to the US Navy, five to the Japanese Navy and, ironically given the initial source of Holland’s funding, the Royal Navy’s first submarine HMS Holland 1. The Holland Torpedo Boat Company became part of the Electric Boat Company which continues to this day as part of General Dynamics.

Similarly I can find no robust evidence that Zaporozhian Cossacks used underwater skiffs against the Turks.

The common Dutch mile was 32 stadia, 4,000 paces, or 20,000 feet (5,660 m or 6,280 m).

It would be remiss of me not to note that Leonardo da Vinci had similarly theorised along similar lines, writing “A candle deprived of air is extinguished, and a bird dies in a closed flask”.

This could have worked, though doesn’t explain the removal of carbon dioxide, and frankly the idea of heating a sufficient quantity of saltpetre in a closed vessel under water for several hours is kind of wild.

He then goes on, very much in classic Pepys style, to talk about two songs he was learning on the lute.

No, I don’t know why either.

Yes, I know that there are detailed, breathless, accounts of the ‘attack’ but I prefer to trust the words of George Washington: “he never did succeed.”

He also developed the world’s first commercial successful steamboat, the North River Steamboat.

The Fenians actually ended up stealing it, but then realised they had no one who knew how to operate it. And then it sank.