A history of… shaving (Part 3)

Pretty much anything was better than injecting acid into hair follicles…

In my previous piece I took the history of shaving up to the 17th century and this week I will (finally!)1 be completing the story of human hair removal and bringing things up to the modern day.

Up until the second half of the 18th century, the act of shaving was laborious and risky. Men typically used a straight razor – a sharp steel blade that folded into a handle, what today we would often refer to as a ‘cut-throat razor’2 – and required considerable skill to wield. Many who could afford it preferred to be shaved by a barber. Satirists at the time quipped that the work of the barber was “to scrape the bristled chin as a farmer scythes the field”, which suggests that a fairly rough, workmanlike approach was taken to the process. Straight razors needed regular maintenance to maintain their edge through frequent honing on whetstones and stropping on leather.3 A pre-shave regimen might involve softening the beard with hot water towels and applying a lather made from soap (by the 1700s, specialised shaving soaps and brushes appeared, with the French often credited with refining the lathering brush technique). Still, even with a steady hand, cuts were common; barbers kept styptic pencils (alums) to stem bleeding, and clients often carried small pieces of tissue to dot onto razor nicks. In an era with only crude antiseptics and no antibiotics (and with a poor understanding of what actually caused infections), a simple cut could easily turn into something more serious.

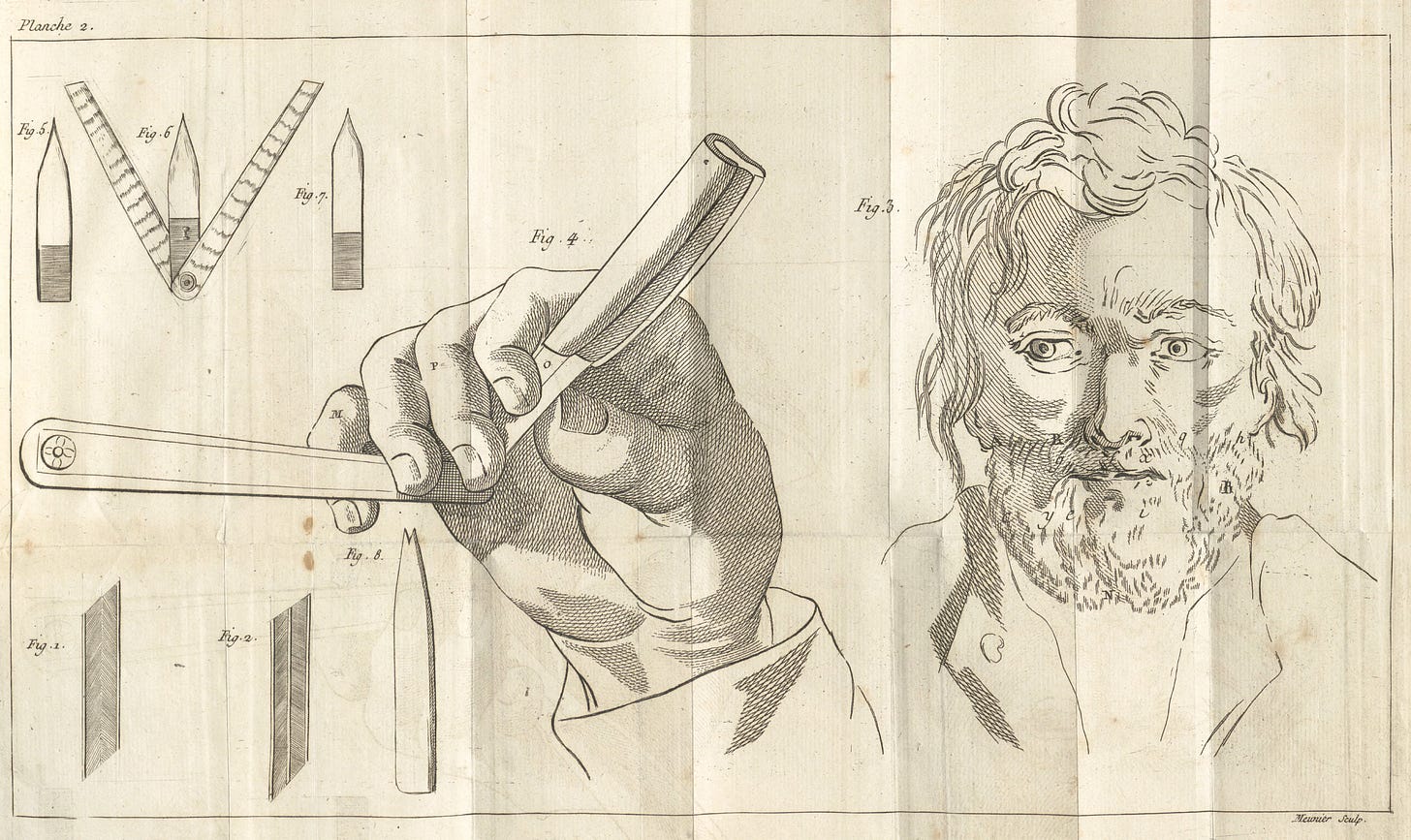

The first attempt to solve this problem and create a safer razor came in 1762, when a French master cutler named Jean-Jacques Perret proposed a guarded razor in his treatise La Pogonotomie (‘The Art of Learning to Shave Oneself’). Perret’s design imitated a carpenter’s plane: he fitted a straight razor with a wooden sleeve that exposed only the blade’s edge, reducing the likelihood of deep cuts. This contraption, essentially a straight razor with a protective guard, is considered the direct ancestor of later safety razors. Perret wrote:

C’est pour épargner aux nouveaux Barbiers le désagrément de ces coupures au visage, que j’inventai, en 1762, le rasoir à rabot…très-commode pour apprendre à se raser soi-même, parce qu’il a l’avantage de bien raser, & aussi près que l’on veut, sans risque de se couper. Je conviens… que le rasoir à rabot demande un peu plus d’attention… Mais… je crois qu’il est bien avantageux de pouvoir se raser sans se balafrer le visage.

I invented, in 1762, the razor with a plane… very convenient for learning to shave oneself, because it has the advantage of shaving well, and as close as one wishes, without risk of cutting oneself. I admit… that the plane-razor requires a bit more attention… But… I think that it is very advantageous to be able to shave without slashing one’s face.

It seems that this “bit more attention” is the reason why what would otherwise appear to be a significantly superior tool to the alternatives on offer at the time didn’t really catch on at scale. Whilst a straight razor could be swiftly cleaned with a single wipe with a towel, the plane razor would get grime and shavings trapped between the wooden sleeve and the blade and was, it seems, a right faff4 to clean. Meanwhile straight razor technology had been improving too. During the Industrial Revolution the quality of razor production improved markedly. A Sheffield cutler named Benjamin Huntsman pioneered a superior crucible steel in the 1740s that allowed for harder, finer razor blades that were both sharper and retained their edge for longer. Soon Sheffield-made, beautiful, straight razors with hollow-ground blades and ornamented handles were being coveted all across Europe.

The result of this innovation led to the second half of the 18th century in Europe being sometimes referred to as the “beardless” era (even so many men only shaved once a week). However, I am mindful of the fact that so far my focus has been almost wholly on men’s hair removal; what of women of the time? Social norms relating to female hairiness in the 18th century were very different from those of today. Incredibly few women would consider removing the hair from their legs (or arms, or armpits) with attention being given only to what was termed “superfluous” hair on the face (and sometimes the neck). In part this was simple pragmatism due to the challenges of hair removal but fashion also played a significant role. Women would expose essentially no flesh from the neck down when in company, legs would be robustly concealed behind stockings, so any hair that might have been there would never be seen.5

When it came to removing those unsightly facial hairs, razors were seldom used both because of the attendant risks associated at the time and for the sake of appearance – it might be okay for a man to have a few nicks on his face but this would have been mortifying for a lady. Rather they would tweezer, or thread, them out, or use one of a bewildering array of depilatory concoctions. Some of these were downright dangerous – many contained arsenic – while others, while being complex, seem unlikely to have been hugely efficacious,6 such as this “approved Depilatory, or a Fluid for taking off the Hair.” from a book published in 1769:

Take Polypody of the Oak, cut into very small pieces; put them into a glass vessel, and pour on them as much Lisbon, or French White Wine, as will rise about an inch above the ingredients: digest in balneo Mariæ (or a bath of hot water) for twenty-four hours; then distil off the liquor by the heat of boiling water, till the whole has come over the helm. A linen cloth wetted with this fluid, may be applied to the part on which the hair grows, and kept on it all night; repeating the application periodically till the hair falls off.

Despite remedies such as this female hair removal remained a challenge for a further century, as this late 19th-century account describes in somewhat gruesome detail:

There is scarcely a physician present who cannot call to mind some lady who has besought him for a remedy to rid her of hair upon the face. What has been done in such a case? Possibly the various depilatories recommended in text-books on Dermatology have been tried and found to be no more serviceable and far more unpleasant than the use of a razor. Possibly an effort has been made to destroy the hairs by inserting hot needles, or injecting acids into the follicles. These mean shaving proved futile, or perhaps harmful, it is possible that a vain attempt has been made to persuade the sufferer that the matter was of little or no consequence, and that cutting the hairs short, or plucking them with tweezers would remedy the evil.

A far better means of remedying this “evil” was eventually developed. In October 1875, a St. Louis ophthalmologist Charles E. Michel published a clinical report describing how he had removed ingrown eyelashes (trichiasis) by inserting a fine needle into the follicle and running direct (galvanic) current from a battery to destroy the papilla – the growth centre of the hair. By 1878 this technique, electrolysis, was being used more widely for aesthetic hair removal, as the proceedings of the American Dermatological Society of that year recount, though it was clearly a not wholly comfortable experience:

Dr. Taylor said that he had been using electrolysis for three or four years, and he employed a very delicate irido-platinum needle for this purpose. He considered the matter of pain quite an important element; and, in consequence of this, several séances7 were ordinarily necessary. He had had good results from this method in the treatment of comedones. Dr. White inquired if the effect was permanent, and in reply Dr. Fox said that no case should be reported until after a considerable time had elapsed. In one case he had removed as many as five hundred hairs, and, although the result was not perfectly successful, it was fairly encouraging. Sometimes hairs would return three months after removal.

Returning once again to razors, in 1847, an English inventor, William Henson, patented a novel razor with a perpendicular blade set on a handle – essentially the first “hoe-shaped” safety razor. Henson’s razor had a guard along one edge of a replaceable blade, mounted at right angles to the handle (much like a modern hoe or a paint scraper). The design was meant to make self-shaving easier by putting the blade at a fixed angle against the skin. A similar idea was later refined and produced in the United States by the Kampfe Brothers, who patented a safety razor in 1880 with a wire guard and a removable (but not disposable) blade. These early safety razors still used blades that required stropping and honing, but they significantly reduced the skill needed – one could shave with less precision in angle and still avoid most cuts.

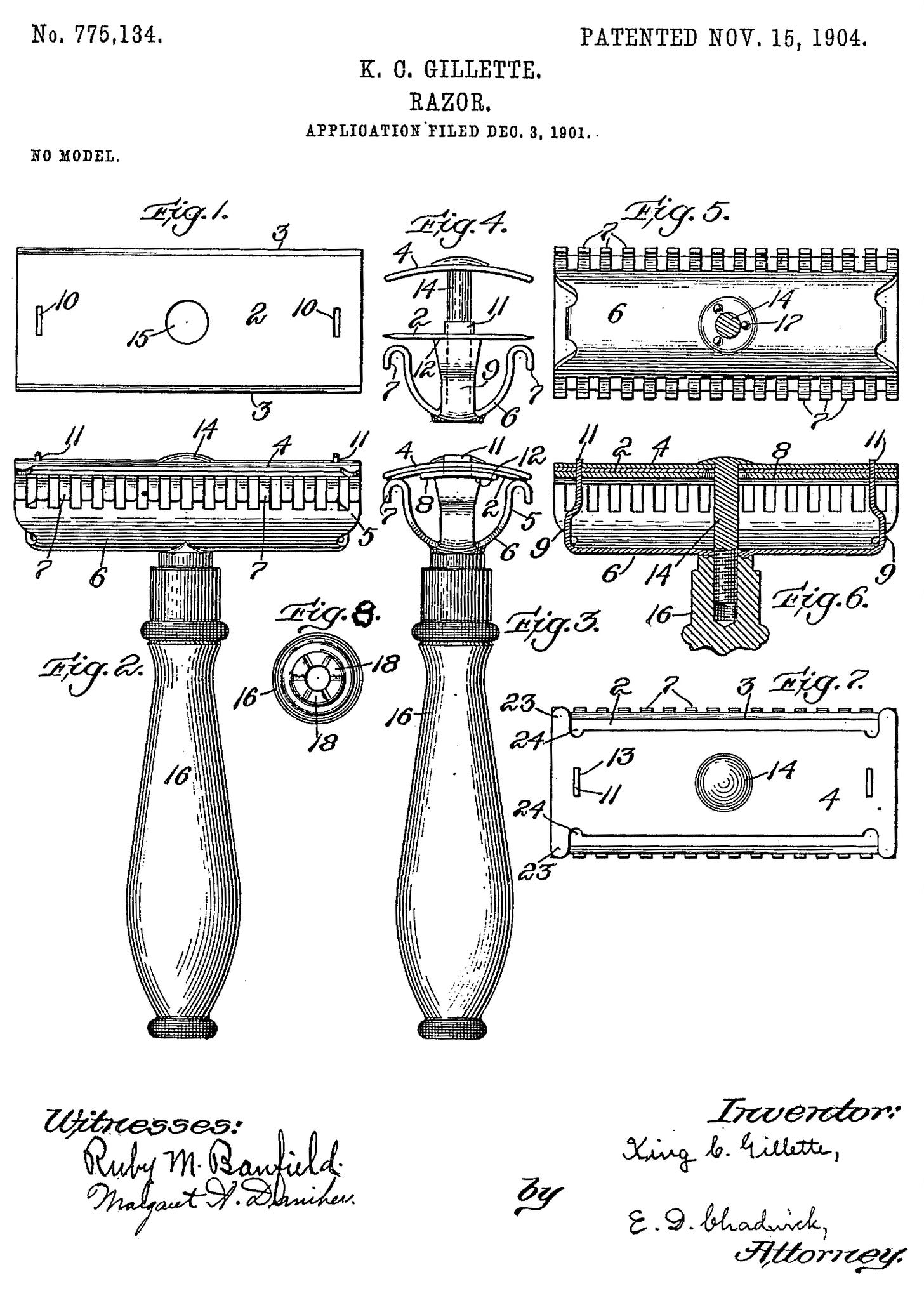

The true revolution in shaving, however, came at the turn of the 20th century with the concept of disposable blades. In 1901, an American entrepreneur named King Camp Gillette8 took out a patent for a safety razor that used inexpensive, thin stamped-steel blades meant to be discarded after a few uses. Gillette, working with engineer William Nickerson, found a way to mass-produce sharp blades cheaply and designed a lightweight double-edged razor to hold them. Introduced commercially in 1903 as the Gillette Safety Razor, this product was a game-changer. For the first time, men could shave themselves easily without needing to sharpen a blade – when the blade dulled, one simply inserted a new one. Gillette’s design had a protective guard and was double-edged (so each blade could be flipped and used twice). The product wasn’t an overnight success. In his first year Gillette only sold 51 razors and 168 blades. In his second year, however he sold 90,884 razors and 123,648 blades.9

The reason for this success was shrewd marketing which emphasised convenience (“No Stropping, No Honing” promised one early advertisement) and targeted not only civilians but also the military. During World War I (1914–18), the US Army issued Gillette safety razors to millions of servicemen (3.5 million razors and 32 million blades were handed out in 1918 alone). This had a lasting impact: daily shaving became a requirement for soldiers (partly to ensure gas masks would seal, a lesson learned on the battlefields) and those soldiers carried the shaving habit home after the war.

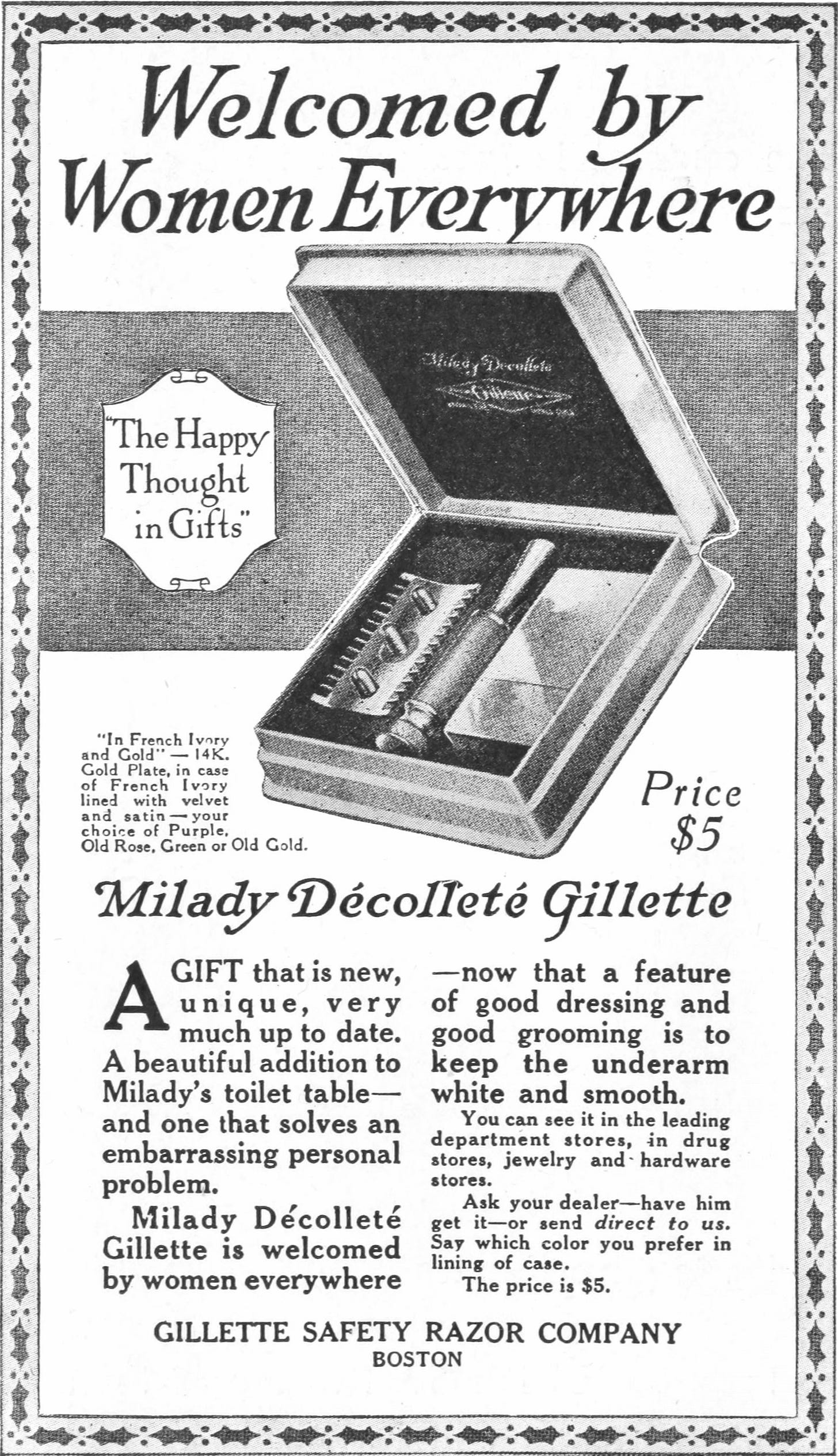

Whilst some women were using electrolysis to remove hairs from their face around this time, it took the launch of the Gillette’s razors for the female hair removal trends that (largely) persist to the this day to develop. In 1915, Gillette introduced the first safety razor for women, the Milady Décolleté, accompanied by an ad campaign in Harper’s Bazaar urging women to remove “objectionable” underarm hair to suit new sleeveless fashions.10 By the 1920s, smooth underarms became de rigueur for Western women, and by the 1940s, with hemlines rising and nylon stockings scarce in wartime, more women also shaved their legs. The trend had become so dominant that by 1964, 98% of American women routinely shaved their legs.

The next major development took place in 1962 when Wilkinson Sword introduced stainless steel blades that resisted corrosion and could be used for many shaves before dulling. At the same time aerosol shaving foam (first invented in 1949) became increasingly popular, removing the need to bother with soap and brushes, speeding up the whole process of getting a hairless face. The ‘cartridge’ style razor system that we use today can be traced back to Wilkinson Sword’s ‘Bonded Shaving System’, launched in 1970, with the first Bic disposable razors launching in 1975. The late 20th century saw razor companies engage in a ‘blade race’, introducing cartridges with two blades (Gillette’s Trac II in 1971), then three, four, and five blades by the 21st century, each promising an ever closer and safer shave. The multi-blade cartridges, often coupled with lubricating strips and pivoting heads, became the new norm in mass-market shaving, and continue to dominate the market.

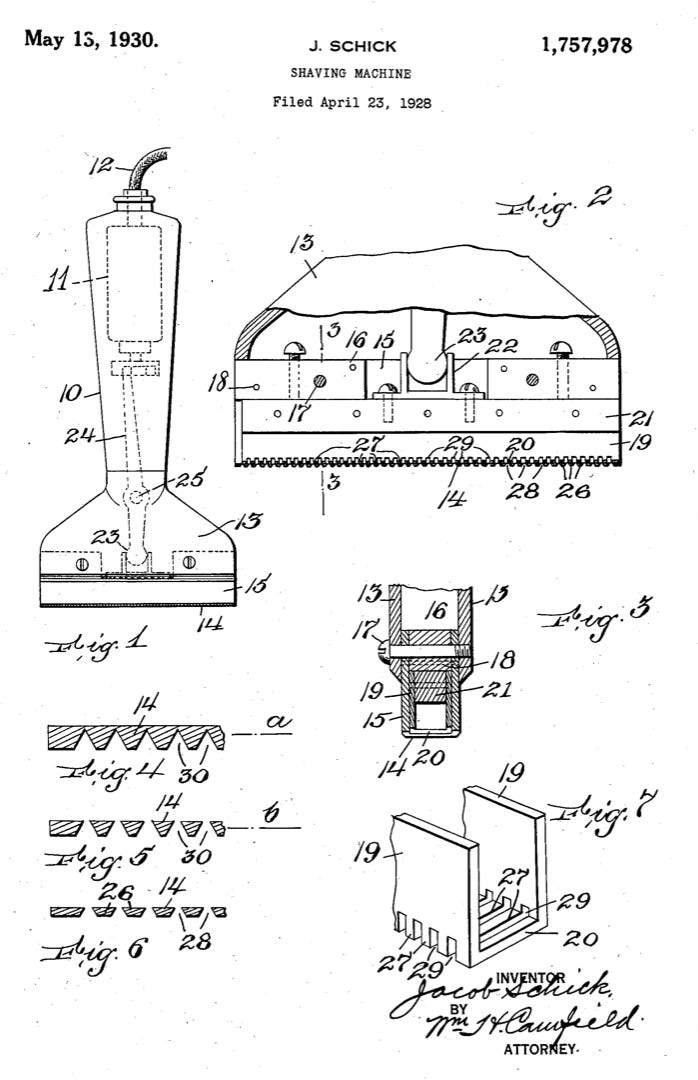

The concept of the electric razor has been around since the late 19th century, with John F. O’Rourke patenting a motor-driven “automatic razor” in 1898, but his invention doesn’t seem to have reached production. In 1915 German engineer Johann Bruecker patented a rotary electric shaver concept but again, this didn’t really go anywhere. It took until 1930 for the electric razor to become a viable product when Col. Jacob Schick received US Patent 1,757,978 for a hand-held “shaving machine”. He launched them in New York the following year, and by 1937 had sold an astonishing 1.5 million devices – an incredible success considering that they cost $25 at launch, or more than $500 in today’s terms.

Inside Schick’s first shaver, a small electric motor spun a shaft. A tiny crank–slider turned that rotation into a rapid side-to-side (reciprocating) motion. Up at the business end sat a thin, toothed shear plate (what we’d now call a guard or “foil”) that lay against the skin. Just behind it, a matching cutter bar with teeth zipped left–right. Beard stubble poked through the shear plate’s slots; every time the moving cutter tooth crossed a slot edge, it sheared the hair clean off—exactly the same principle long used in powered hair clippers, just miniaturised and sealed into a hand unit.

Personally I have never really got on with electric razors, so as I am a bit stubbly this morning I will finish now and use a three-bladed device with a pivoting head and lubricating strip to remove my bristles, and reflect as I do so quite how long and intriguing the history of this tool is.

Did I have any idea when I started this I’d end up writing around 8,000 words about the history of shaving? No, no I did not.

I have never had what one might term a ‘proper’ shave with a cut-throat razor, but having learned so much about shaving I am very tempted to seek one out.

I never previously understood the purposes of running a razor along a leather strop, but now I do! After sharpening on a stone, a fragile wire edge (burr) often clings to the apex of the blade. Edge-trailing passes on leather flex the burr back and forth and tear it away cleanly, leaving a crisp apex. Using the razor can also leave the very tip of the blade rolled or slightly out of line. The strop’s slight give plus light tension coaxes the apex straight again. The reason that leather works is because has it fine, naturally abrasive silica and chrome salts embedded in it from tanning and use. Strops can also have additional abrasive grits added to them to improve their function.

For non-British readers, ‘faff’ is an idiom meaning ‘hassle’.

You may be wondering, as I did, why female nudes in the art of the period were the exception to this rule, being almost always hairless. Were artists’ models shaved? The answer is no – artists were generally trying to represent female purity based upon classical ideals, which meant ‘hairless’, so the hair on these models was oil-brushed out.

The same book suggests the following to improve skin tone. I am very dubious about the final option: “The Juice that issues from the Birch-Tree, when wounded with an auger in spring, is detersive and excellent to clear the complexion: the same virtue is attributed to its distilled water. Some people recommend Strawberry-water; others the decoction of Orpiment, and some Frog-spawn-water.”

French for ‘sitting’ or ‘session’ now generally only used in the context of mediums, it was used more generally to describe medical procedures back then.

Yes, that really was his name. No, I don’t know either.

Some sources say that he actually produced two million blades that year, which seems more likely given the number of razors that he sold.

These razors were not cheap though. Depending upon how one measures it; $5 in 1916 is the equivalent of $165-360 today.

You might like to read a poem titled ‘The Man from Ironbark’ before having that cutthroat shave!