A history of… shaving (Part 1)

It was important to shave before battle, lest your enemy hang on to your beard...

When I am rooting around for a topic to write about for these pieces inspiration often seems to strike me in the bathroom (I have done them variously on deodorant, shampoo, toilet paper, toilets, showers, and toothbrushes) and while shaving this morning I suddenly thought… well you can probably figure out the rest.

If you look online you will often see it claimed that shaving dates back to Palaeolithic times, with obsidian blades1 or sharpened clam shells used for the job (or even pairs of clam shells used as ersatz tweezers to pluck out offending hairs). The reality is that this is speculative at best. We don’t really know if ancient humans shaved (or plucked) – later encounters with peoples of a similar technology level, recorded in the histories of the last couple of millennia show evidence of such shaving, so it is probably true, but by no means certain. What we can be sure of is that shaving was taking place in the early Bronze Age, around 5,000 years ago, as we have both the tools and the written records to support this. The fact that one of the first tools humans made when they learned how to fashion metal was the razor does tend to suggest that shaving had already been a thing, potentially for thousands of years already. Alternatively, it could have been that the practice became common only when a decent tool for the job became available.

The earliest evidence for shaving comes from ancient Egypt, where archaeologists have discovered solid copper and even gold razors buried in tombs dating to the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods (c. 3000–2500 BCE). These razors often had round heads or crescent shapes and were likely used with water and abrasive pastes as a shaving aid.

Their presence in elite burials (including pharaonic tombs) underscores the cultural importance Egyptians placed on shaving and personal grooming, as bodily hair was viewed as unclean or uncivilised in Egyptian society. Both men and women of the upper classes removed body hair; noblewomen often kept their heads clean-shaven (wearing wigs in public) and considered the presence of pubic hair to be undesirable. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, noted the extreme meticulousness of Egyptian priests in removing hair:

οἱ δὲ ἱρέες ξυρῶνται πᾶν τὸ σῶμα διὰ τρίτης ἡμέρης, ἵνα μήτε φθεὶρ μήτε ἄλλο μυσαρὸν μηδὲν ἐγγίνηταί σφι θεραπεύουσι τοὺς θεούς.

Their priests shave the whole body every other day, so that no louse or anything else foul may breed on them while they attend upon the gods.

This passage also emphasises an important point – in a world where lice were common the shaving of hair was not only carried out for aesthetics, it was also an effective means of removing parasites. Shaving was not the only method used by Egyptians to remove hair, they also had a range of depilatory ointments, and the recipes for some of these have survived on ancient papyri. I must confess I am convinced neither by their likely effectiveness nor their pleasantness:

Boiled turtle shell, crushed; mixed with the leg fat of a hippopotamus or water-buffalo; applied repeatedly.

Boiled & crushed bird bones, fly dung, sycamore juice, gum (sometimes with cucumber); heated and applied, presumably pulled off when cool.

Burnt krtus leaf steeped in oil (it is suggested that this could be applied to the head of someone who had wronged you in order to cause them to lose their hair!)2

In Mesopotamia, by contrast, attitudes toward hair were very different. The Sumerians and Akkadians of the 3rd–2nd millennium BCE generally regarded a well-tended beard as a sign of masculinity, wisdom, and social rank. Mesopotamian men, especially kings and dignitaries, tended to keep their beards but groomed them meticulously – oiling, braiding, and waxing them into elaborate ringlets as seen on sculptures and reliefs. Nonetheless, shaving and hair-trimming were also practiced when circumstances required. A clear illustration of this comes from the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 18th–12th century BCE). In this saga, Enkidu – a wild man covered in hair – is tamed from his primal state and integrated into human society. At the crucial moment of his “civilizing,” Enkidu’s body hair is removed:

He had his hair cut, he washed, he rubbed sweet oil into his skin, and became fully human

Ancient legal and ritual texts also indicate that forced shaving could be a punishment or a marker of humiliation in the Near East. For instance, a story in the Hebrew Bible (2 Samuel 10:4) recounts that the Ammonite king Hanun, to insult Israelite envoys, “seized them and shaved off half of each man’s beard,” an action so degrading in that culture that the men dared not return home until their beards regrew. This half-shaving punishment was also used by the Spartans, inflicted upon cowards, as Plutarch recounts in his Life of Agesilaus:

One great one [law] was then before them concerning the runaways (as their name is for them) that had fled out of the battle, who being many and powerful, it was feared that they might make some commotion in the republic, to prevent the execution of the law upon them for their cowardice. The law in that case was very severe; for they were not only to be debarred from all honours, but also it was a disgrace to intermarry with them; whoever met any of them in the streets might beat him if he chose, nor was it lawful for him to resist; they, in the meanwhile, were obliged to go about unwashed and meanly dressed, with their clothes patched with divers colours, and to wear their beards half shaved, half unshaven.

By the first millennium BCE, clear regional differences had emerged in shaving customs. In the Classical Greek world (c. 8th–4th century BCE), adult men traditionally wore beards as a sign of maturity and status. Among the Greeks, a clean-shaven face on a grown man was initially uncommon and could even be viewed as effeminate or youthful. In Athens of the 5th century BCE, for example, men only cut their beards during periods of mourning. Things began to change, however, during the time of Alexander the Great (who was always portrayed as being clean-shaven). According to later historians, Alexander (356–323 BCE) instigated a shaving revolution. During his eastern campaigns, Alexander reputedly ordered his Macedonian soldiers to shave their faces clean before the decisive Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE). The classic explanation, recorded by Plutarch, was practical: beards gave enemies an easy handhold in close combat:

τοῦτο δὲ ἀμέλει καὶ Ἀλέξανδρον τὸν Μακεδόνα ἐννοήσαντά φασι προστάξαι τοῖς στρατηγοῖς ξυρεῖν τὰ γένεια τῶν Μακεδόνων, ὡς λαβὴν ταύτην ἐν ταῖς μάχαις οὖσαν προχειροτάτην.

And Alexander of Macedon, having considered this, as they say, ordered his generals to have the Macedonians’ beards shaved, since these offered the readiest grip in battle.

Whether this actually happened or not (Plutarch was writing centuries later) Greeks certainly took to shaving at around this time. Barbershops (τα κουρεία) became common in Greek cities, and daily shaves and haircuts turned into a social ritual for gentlemen.

Meanwhile early Romans of the Regal and Republican eras (6th–4th c. BCE) initially followed the old Italic custom of wearing beards. Pliny the Elder reports that Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BCE) dated the introduction of professional barbers (tonsōrēs) to around 300 BCE:

omnino tonsores in Italiam primum venisse ex Sicilia dicuntur… eosque adduxisse Publium Titinium Menam.

Barbers are said to have first come to Italy from Sicily in the 453rd year after Rome’s founding [300 BCE]… and that Publius Titinius Mena brought them.

Prior to this, Romans either let their hair grow or trimmed it themselves in a primitive way. The very Latin word for razor, novācula, does not appear in literature until this period. According to the Roman historian Livy, the legendary King Lucius Tarquinius Priscus in the 6th century BCE had introduced the novacula (razor) to Rome3 but even Livy implies that regular shaving was not adopted by the populace at that time. One shaving trend-setter was the great general Scipio Aemilianus (185-129 BCE). Pliny the Elder records that Scipio “was the first of all to institute shaving every day”.

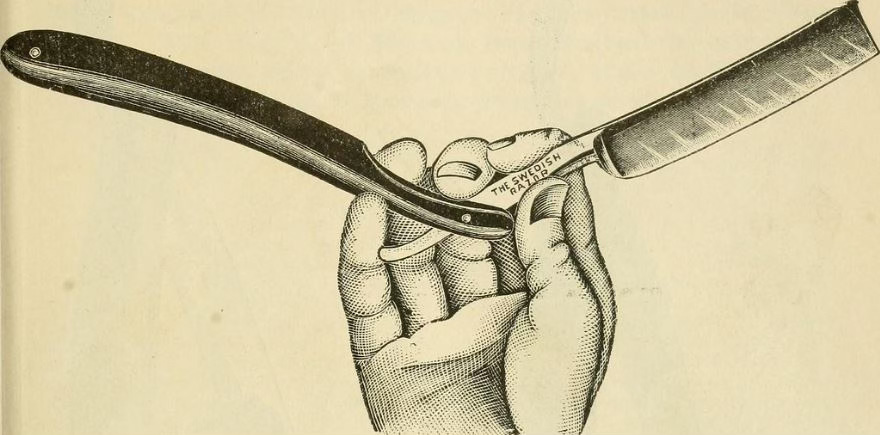

In time barbering became big business in Rome. The Latin poets and satirists of the early 1st century BCE (e.g. Plautus, and later Horace) frequently mention the daily morning visit to the barber as part of a gentleman’s routine. Barber shops (tonstrinae) doubled as social hubs where news and gossip were exchanged. However, shaving in this era was still a perilous affair: Roman razors were made of bronze or iron and needed to be kept very sharp; nicks and cuts were common, and in a world without antibiotics infections could be debilitating or even fatal. If you were rich enough you would have your own dedicated barber slave, the accuracy of whose work you could be certain of. Soon a man’s first shave (the depositio barbae) would become a significant rite of passage marking the transition from youth to adulthood. Typically around age 21, a young man would shave for the first time in a special ceremony, often dedicating the shorn beard hair to a god (such as offering it in a box to Jupiter). Emperor Nero, for example, staged an extravagant celebration upon his first shave, the juvenalia, and encased his shaven beard in a golden box to dedicate in the Capitol.4

Julius Caeser was also noted for his grooming,5 as Suetonius reports in his Lives of the Caesars (c. 110 CE):

Cultu corporis nimium studentem fuisse; non modo tonderi diligenter ac raderi solitum, sed etiam superfluos pilos vellere…

He [Julius Caesar] was said to be excessively attentive to personal appearance; not only accustomed to have his hair cut and beard shaved meticulously, but even to pluck out stray hairs.

Caesar himself records that his foes, the ancient Britons, tended to favour the moustache, recording in his Gallic War, “They wear long hair, and shave every part of the body save the head and the upper lip.”6

Around the same time in Asia there were a number of different views on shaving. In the Indian subcontinent, hair practices were governed largely by religious and caste norms. Since at least the time of the Buddha (5th century BCE), monastic communities in India embraced head-shaving as a sign of renunciation: Buddhist monks shaved their heads (a practice the Buddha himself instituted for his followers), and Jain monks even plucked each hair out by the root to avoid vanity. Meanwhile, orthodox Hindu society treated hair in complex ways – the Manusmṛiti and other Dharmaśāstras prescribed that high-caste men keep a shikha (tuft of hair) on the crown but shave the rest of the head in certain rituals, and that widows or renunciants remove their hair as a symbol of worldly detachment.. Daily beard-shaving was less universally prescribed, but urbane and courtly culture under the Mauryas and Guptas (4th c. BCE – 5th c. CE) did include razors. The medical compendium Suśruta Saṃhitā (c. 1st millennium BCE) mentions razors (muṇḍa) among surgical instruments and advises shaving the surgical area – one of the earliest records of pre-operative shaving in medical history,

In China, on the other hand, the classical attitude toward shaving was coloured by Confucian values that regarded the hair and body as sacred gifts from one’s parents (and thus not to be cut). During the Warring States and Han dynasty (5th c. BCE – 3rd c. CE), the typical Han Chinese man grew out the hair on his head long, often into a topknot, and did not shave his face completely – moderate facial hair like mustaches or goatees were common. A saying attributed to Confucius goes: “To not destroy the body one has received from one’s parents is the beginning of filial piety.” As such, adult men rarely shaved their heads or faces entirely. There were, however, exceptions. One was punishment: criminals might be sentenced to have their head shaved (along with a brand on the face) – a punishment called ti* (剃), literally “shaving”, used in the Qin and early Han to mark disgrace. Another exception was the emergence of Daoist and Buddhist monks. When Buddhism entered China in the 1st century CE, monks followed the Indian tradition of shaving the head (which local observers found shocking at first). By the late classical period (c. 4th century CE), the image of the shaven-headed monk became familiar in China, though it remained a sign of religious devotion set apart from normal society.

In my next piece I’ll explore the conflicting Christian views about the holiness of beards, the rise of the barber-surgeons, the invention of the modern razor, and a brief digression describing how Samuel Pepys attempted to shave with a pumice stone. But I’ll end today with a rather astonishing shaving story which was heard by Usāmah ibn Munqidh (1095–1188), and reported in Kitāb al-Iʿtibār (The Book of Learning by Example, named in translation as “An Arab-Syrian Gentleman and Warrior in the Period of the Crusades: Memoirs of Usāmah ibn-Munqidh”). It describes how a Frankish crusader knight in northern Syria discovered that parts of the body other than the face could be shaved:

We had with us a bath-keeper named Sālim, originally an inhabitant of al-Maʿarra, who had charge of the bath of my father (may Allah’s mercy rest upon his soul!). This man related the following story.

I once opened a bath in al-Maʿarra in order to earn my living. To this bath there came a Frankish knight. The Franks disapprove of girding a cover around one’s waist while in the bath. So this Frank stretched out his arm and pulled off my cover from my waist and threw it away. He looked and saw that I had recently shaved off my pubes. So he shouted, “Sālim!” As I drew near him he stretched his hand over my pubes and said, “Sālim, good! By the truth of my religion, do the same for me.” Saying this, he lay on his back and I found that in that place the hair was like his beard. So I shaved it off. Then he passed his hand over the place and, finding it smooth, he said, “Sālim, by the truth of my religion, do the same to madame [al-dāma]” (al-dāma in their language means the lady), referring to his wife. He then said to a servant of his, “Tell madame to come here.” Accordingly the servant went and brought her and made her enter the bath. She also lay on her back. The knight repeated, “Do what thou hast done to me.” So I shaved all that hair while her husband was sitting looking at me. At last he thanked me and handed me the pay for my service.

Certainly incredibly sharp, ancient, obsidian (and flint) blades have been found which could have been effective razors, but whether they were used for this purpose is, alas, unclear.

I am not entirely sure how one would do this without the victim noticing.

I more inclined to believe Pliny’s date.

I am sure it was a great party, but it does seem like quite a weird thing to celebrate. Having said that, given what Nero later got up to late, this is probably quite far down on the weirdness scale.

He was much irked by his receding hairline though, which he attempted to conceal with a comb-over.

Caesar was known to, err, make things up, but it seems that this description is likely to be accurate.