A history of… pizza

According to one Victorian reporter "The pizza shops are about the filthiest in Naples, and whoever knows Naples will admit that is saying a good deal."

I love pizza. I love eating pizza. I love making pizza (and then eating it, of course). I have had a number of pizza exploits over the years, including once cooking pizza (making the dough from scratch) for 30 people in the middle of a high-altitude desert in Nevada using a portable wood-fired oven. I can think of no better reason, therefore, to have a bit of a delve into its history.

If you pare it down to its core, pizza is essentially a flat piece of bread, with stuff on it that has been cooked. Flatbread, it turns out, is incredibly old. A team of archeologists from the University of Copenhagen and University College London working at the Shubayqa 1 site in the Black Desert of northeast Jordan found the charred remains of some flatbread that is an astonishing 14,400 years old. The lead author of the paper about this discovery commented:

Bread pre-dates agriculture by at least 4,000 years in the Levant. We now have to reconsider the relationship between bread-making and the origins of agriculture.

Okay, so this isn’t a real pizza, but it isn’t hard to imagine it sprinkled with oil, olives, and herbs being a kind of proto-pizza. Flatbread was a staple part of the diet of ancient Egyptians, and they were making it at least as long as 5,000 years ago. From tomb paintings and records it seems like that his bread was eaten topped with onions and garlic, and potentially even cheese – tantalisingly close to being a pizza! As for how this bread was made, we have this fascinating account from Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE):

They eat bread made from spelt (emmer), for they grow no other kind of grain, and this is kneaded with their feet.

An interesting method but one, err, it seems almost certain that Herodotus made up, as paintings clearly show Egyptians kneading dough with their hands. For thousands of years, well into the late middle ages in Europe, flatbreads were used instead of plates. Cooked food would be put on them and the bread would soak up all of the juices and sauces and be eaten at the end. It is probably stretching things to consider this to be a type of pizza, but this type of dining played a role in the siege of Troy (c.1250 BCE). In Virgil’s Aeneid (c.29 BCE) he recounts that Calaeno, the queen of the Harpies, foretold that the Trojans would not find peace until they were forced by hunger to eat their tables. In Book VII Aeneas and his men prepare flatbreads topped with cooked vegetables. When they eat the bread they realise that they are eating their ‘tables’, thus fulfilling the prophecy.

A number of online sources claim that the Persian soldiers of Darius the Great (c.550–486 BCE) made flatbreads on their heated shields, and some say that they then put cheese and dates on these breads, making a form of pizza. I cannot, alas, find any even vaguely contemporaneous sources to back this up and fear that it is a much later invention.

Something that we can be sure of is baking was going on in ancient Rome. We have, from Marcus Cato’s On Agriculture (c.160 BCE), a recipe for a tasty-sounding cheese flatbread, again not quite pizza but not a million miles from it:

Recipe for libum: Bray 2 pounds of cheese thoroughly in a mortar; when it is thoroughly macerated, add 1 pound of wheat flour, or, if you wish the cake to be more dainty, ½ pound of fine flour, and mix thoroughly with the cheese. Add 1 egg, and work the whole well. Pat out a loaf, place on leaves, and bake slowly on a warm hearth under a crock.

Right, enough of almost-pizzas and proto-pizzas, when did pizza as we know it first arise?1 The honest answer is that we don’t know for sure. Surprisingly the earliest recipe for something like today’s pizzas comes not from Italy, but from France. A document from Provence from 8792 describes a Pissaladière as leavened flatbread topped with onions, olives and anchovies.

The earliest recorded usage of the word ‘pizza’ itself is more than 1,000 years old, dating from 997, and occurs in the charter of the town of Gaeta in southern Italy:

duodecim pizze, et alios duos solidos in Kalendis Maii de consuetudine, et alios duos in festo Sancti Petri et Pauli…

Twelve pizzas, and two more solidi (coins) on the Kalends of May by custom, and another two on the feast of Saints Peter and Paul…

This was essentially a rental payment, made to the local bishop, by one of the tenants of his land. It amuses me to think that the first mention of pizza coincides with the first mention of a pizza delivery! This was, however, still not pizza as we would know it. It was most likely a focaccia bread, proved and risen like modern pizza, but there the similarity ends. Indeed Benedetto di Falco, writing in 1535 about cuisine of Naples, says that “Focaccia in Neapolitan is called pizza”. Around the same time we have the dish sardenaira being eaten in the Liguria region of Italy. Often called pizza all'Andrea, after admiral Andrea Doria (1466–1560) it is topped with olive oil, garlic, anchovies and capers but again is something of a halfway house between modern pizza and focaccia.

For truly modern pizza we need to turn to Naples in the 18th century. A bustling port city, its largely working-class population lived cheek-by-jowl in cramped buildings that often lacked cooking facilities. They needed cheap food that could be eaten on the go, and pizza was the perfect solution. In the 1789 book Collezione di tutti i poemi in lingua Napoletena (Collection of all poems in the Neapolitan language)3 we have a detailed list of the pizza-type things available there:

Pizzella. It is a generic name for all types of cakes, focaccias, schiacciate; and therefore some adjectives are added to distinguish them. Here are the main ones. Fried pizza. Pizza a lo furno co l’arecheta. Pizza rognosa. Pizza sedonta. Pizza torn. Pizza di cicoli doce. Pizza di ricotta. Pizza rustica.4 Pizza d’ova faldacchere. Pizza di bocca di Dama Oc.

The passage goes on to explain the origin of the word:

With respect to etymology, we believe that it derives from the Latin word pistus, pista, pistum, which the ancients particularly used to stir the dough; hence the words pistores, pistura, and we offer, that even the Italians called our pizzas schiacciate, because in fact the simplest ones consist of nothing more than a piece of dough crushed between the hands, and then with some seasoning put in the pan, or in the oven.

And as for who made the best pizzas?

For some of these the Monasteries of our Nuns were illustrious. It would have been worthy of our loving zeal for the homeland to hand down to posterity an exact description of the preparations of many types of pizza; but since cooking is a part of Chemistry and therefore belongs to the class of the most simple sciences, it did not seem appropriate to us to include it in this Vocabulary intended only for the information of names, and not of things.5

For a first-hand account of Neapolitan pizza we have the great Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870) who travelled to the city in 1835:

We deceive ourselves strangely. The Neapolitan of the lower class is not wretched; for his necessities are in exact harmony with his desires. What does he wish to eat? A pizza.

A pizza of two farthings suffices for one person, a pizza of two sous is enough to satisfy a whole family. At first sight, the pizza appears to be a simple dish, upon examination it proves to be compound. The pizza is prepared with bacon, with lard, with cheese, with tomatoes, with fish.

He goes on to explain how one can assess the abundance of other foodstuffs simply by looking at the prices of pizzas:

It is the gastronomic thermometer of the market. The price of the pizza rises and falls according to the abundance or scarcity of the year. When the fish-pizza sells at a half grain, the fishing has been good; when the oil-pizza sells at a grain, the yield of olives has been bad.

The price of pizza was not only determined by the cost of its ingredients, a lot depend upon how old it was:

The rate at which the pizza sells is, also, influenced by the greater or less degree of freshness; it will be easily understood that yesterday’s pizza will not bring the same price as today’s. For small purses, they have the pizza of a week old, which, if not agreeably, very advantageously, supplies the place of the sea-biscuit.

The earliest reference I can find to pizza in an English newspaper dates from the London Morning Post, 22nd December 1860:

Well, the pizza is a favourite Neapolitan delicacy, which is only made and eaten between sunset and two or three in the morning, and it must be baked in five minutes in the oven; at the very moment when it is ordered it is pulled out of the oven and served up piping hot, otherwise it is not worth a grano.

The piece then goes on to describe the preparation of the dish in mouthwatering detail:

The pizza baker takes a ball of dough, kneads it, and spreads it out with the palm of his hand, giving it about half the thickness of a muffin, then pours over it mozzarella, which is nothing more than rich cream beaten almost like a cream cheese; then he adds grated cheese, herbs and tomato, puts the cake—which, made after this fashion, is termed the pizza—just for five minutes into the oven, and serves it up as hot as possible. The cheese and the cream are of course all melted and unite with the herbs and tomato. The outside crust must, in the case of a perfect pizza, possess a certain orthodox crispness.

At this point pizza had evolved from being the preserve of the working classes and become a more egalitarian dish:

Now, at this season of the year there is no person, high or low. From the first Neapolitan duke to the lowest lazzaroni, with whom it is not a primary article of faith to eat pizza. The pizza cake is your only social leveller, for in the pizza shops rich and poor harmoniously congregate; they are the only places where the members of the Neapolitan aristocracy—far haughtier than those in any other part of Italy—may be seen masticating their favourite delicacy side by side with their own coachmen, and valets, and barbers.

Our humble correspondent was, however, somewhat snooty about the standards of hygeine involved in its prepartion:

The pizza shops are about the filthiest in Naples, and whoever knows Naples will admit that is saying a good deal. They are generally in the meanest alleys and in the midst of the most disreputable quarters. No matter, at this season of the year, they are thronged all the same.

Originally Neapolitan pizza sellers would make their pizza in wood-fired ovens then take it out to sell on the street. This presented a challenge – how to keep the pizza warm? The answer, it seems,6 is that they would coil wet towels upon their heads, balance a small coal stove on top of that, and stash the pizza above the stove! In time it transitioned into a more refined food that one would sit down to eat, the pioneer of this being the Antica Pizzeria Port’Alba. Founded as a simple food stand in Naples in 1738, in 1830 they opened what is generally considered to be the world’s first pizzeria using lava rocks from Mount Vesuvius to line its ovens. The place soon became a hang-out for students and intellectuals – groups not known for being the most flush with cash. To overcome this issue they introduced a payment system, called pizza an otto, was developed that allowed customers to pay up to eight days after their meal.7 The restaurant remains open to this day, and I long to visit it!

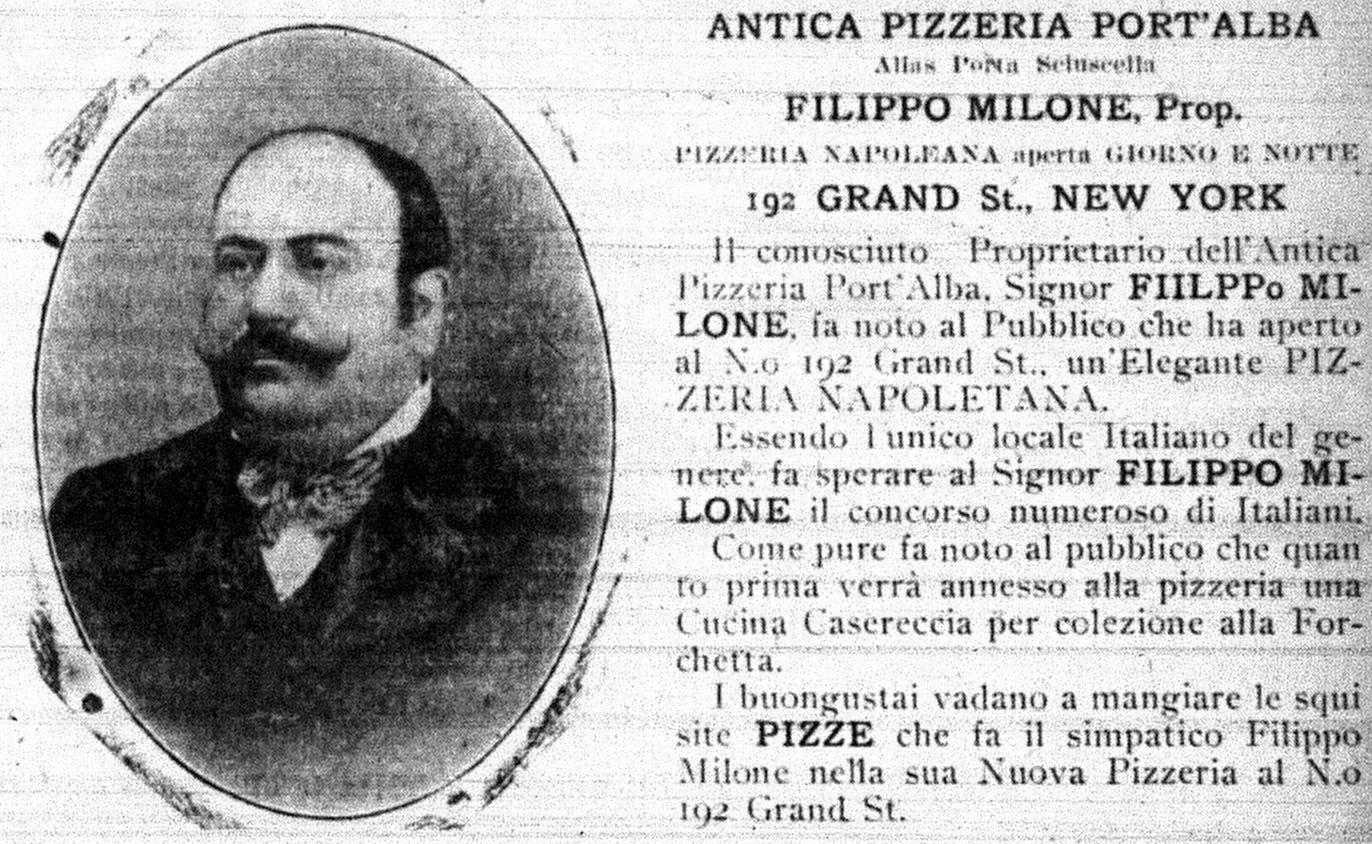

Italian immigrants brought pizza to America during the 19th century, and were making it at home for decades before a similar establishment was opened in that country. The pioneer of American pizzerias was Filippo Milone who probably arrived in the country in 1892. He opened a bakery-come-grocers at 53½ Spring Street, New York, in 1898 and started selling pizzas not long afterwards, going on to establish another five restaurants in the city.

Milone has, very sadly, been mostly airbrushed from history to the benefit of one his staff members, Gennaro Lombardi. Born in Italy in 1887, Lombardi arrived in New York in November 1904 (more than a year after this advert). He began working in 53½ Spring Street shortly afterwards, and appears to have acquired it in 1908. Renamed ‘Lombardi’s’ in 1939, it is claimed to be first pizza restaurant in the USA – which it might have been8 but he didn’t found it! As for Milone, he died childless in 1920 and is buried in an unmarked grave in Queens, his contributions to pizza largely forgotten. Nonetheless he played a crucial role in building what is now a global business exceeding $150 billion dollars a year in sales. Thank you Filippo, I know what I am having for dinner tonight…

Yes, this is a pun on the fact that our pizzas are leavened, unlike ancient flatbreads. Is it a good pun? No.

I have tried very hard to substantiate this and find the primary source, but have sadly failed. The secondary source seems pretty robust though.

It doesn’t seem really to be a book of poems at all, rather, as the later passage explains, it is more of an elaborate dictionary. I am somewhat confused by the title!

I can’t help but wonder if this is akin to the pizza rustica one can buy today.

I, for one, am very upset that the recipes were not included.

I am not convinced about the robustness of the sources I can find relating to this.

Some wags joked that you could get your last meal for free, so long as you died before the eight days were up.

Actually, it wasn’t. Giovanni Albano founded a pizzeria located at 59½ Mulberry Street, New York, in 1894, but he didn’t expand the way Milone did, so I am cruelly excluding him from the main body of this piece. Sorry Giovanni.

Well, that's the way that history works -- The Italians couldn't really make pizza until they had invented tomatoes...

As someone who spent two of his teenage years working in a Pizza Hut and periodically getting his arm burned by the oven, I appreciate this.