A history of… pineapples

In 18th-century London there was a thriving pineapple rental market…

It is my friend Jess’s birthday tomorrow,1 so today she’ll be making her traditional upside-down pineapple cake for the celebration. In honour of this I’ll be exploring the history of its key ingredient.

The pineapple (Ananas comosus) is indigenous to tropical South America, where it was domesticated by Native American peoples long before the Columbian Exchange. The origin of cultivated pineapples is a little uncertain. Traditional accounts point to the region around the Paraná–Paraguay river basin (in present-day southern Brazil, Paraguay and northern Argentina) as the pineapple’s original homeland This area is home to several wild relatives of Ananas. Modern genetic studies, however, suggest that the north-eastern areas of South America, especially the Guiana Shield, may have been the primary domestication centre.

Domesticated pineapple cultivation may have begun as far back as 6,000–10,000 years ago. Archaeological remains suggest that by around 1200–800 BCE pineapples were already being used or grown in parts of coastal South America, and by the time of European conquest in the late 15th century, pineapple cultivation was ubiquitous across the Neotropical Americas: it was grown from the lowlands of Central America and the Caribbean, through Amazonia, all the way south to Paraguay and the foothills of the Andes.

Domestication profoundly transformed the pineapple plant. Wild pineapples bear much smaller, seedy fruits, but indigenous peoples selectively bred plants for larger, sweeter, seedless fruits over many generations. The result was the cultivated pineapple, which is nearly seedless and must be propagated vegetatively (by planting shoots or crowns) rather than by seed. Through human selection, pineapples developed more numerous and bigger fruitlets (the ‘eyes’ on the rind) and a more robust morphology – shorter, broader leaves and a sturdier stem to store starch – yielding bigger, juicier fruit. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo in his Historia general y natural de las Indias (1535) wrote that:

This fruit grows in small, low bushes… The crown [head] of the fruit is cut off and planted, and from it another pineapple grows. And also, the same plant puts out some offshoots around it, and from each of these another pineapple is produced; and thus they multiply very quickly.

The Tupi–Guarani people of Brazil were among those who first cultivated the plant, calling it naná meaning ‘excellent fruit’. Through propagation clones of the parent plant were created, ensuring the retention of desirable traits like sweetness and lack of seeds. The ease by which this could be done helped the fruit spread rapidly from village to village. In fact, the very names for pineapple in dozens of Indigenous languages (variations of nana/ananás) spread along with the plant itself.

When the Europeans arrived in the Americas at the end of the 15th century2 they became immediately enamoured with this delicious fruit. The first European mention of them comes from 1493 when Columbus recorded in the journal3 of his second voyage:

They found many pine cones (piñas) such as those which are brought to Spain from the lands of the Indies, which are very delicious fruits and of good fragrance, although not as tasty as ours.4

We have a more detailed description from Diego Álvarez Chanca, who was a doctor on the same expedition:

Among other fruits they [the Indians] have one which is like a pine-cone, but much larger, which fruit is the most delicious thing I have ever tasted; and it is called ‘anana’ by the Indians. In size it is like two fists and larger in circumference. Its exterior is like that of a pine-cone, and it is gathered before it is entirely ripe and is set aside to ripen. If it were eaten unripe it would be dangerous. When it is ripe it is yellow and is exceedingly sweet and fragrant, and it can be eaten in the morning and evening.

The extent of the Spanish infatuation with the pineapple is perhaps best conveyed by the words of Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557) who continued in his Historia general y natural de las Indias:

The pineapple is the most beautiful of all the fruits I have seen in the world, for me the best and most delicious, and it is the fruit the Indians call naná. Its shape is like that of a pine cone, though much larger and more beautiful, and of much better flavor and fragrance; it is golden in color outside and inside, and when ripe it is soft and very pleasant to eat. By my life, it is the best fruit I have ever eaten in the world, and though in Castile there are many and very good fruits, none in my opinion equals it. In sum, no fruit is comparable to the pineapple, which may well be called the prince of all fruits.

As you can imagine European nobility, upon reading these accounts, were salivating at the prospect of tasting this incredible fruit. There was a problem though: they couldn’t. Pineapples would rot on the voyage across the Atlantic (there is a story that one survived the trip to be eaten by King Ferdinand II of Spain in 1494, but this is probably not accurate)5 and they couldn’t be grown in European climes. As Valdés goes on to explain:

It is a fruit of the hot lands, and in Castile it has not been seen nor will it be, unless it is taken there, and from experience I know it was taken to Castile, but it did not grow there. And truly, I do not wonder that it does not grow in Castile, because there is not the necessary heat for this fruit to be produced and ripen as it should.

The pineapple is a very healthy fruit, and there is no Indian or Spaniard who does not value it highly; and if there were means to carry it to Castile without it being lost or spoiled, it would be much esteemed there, for it is the best fruit that exists in the Indies and in the world.

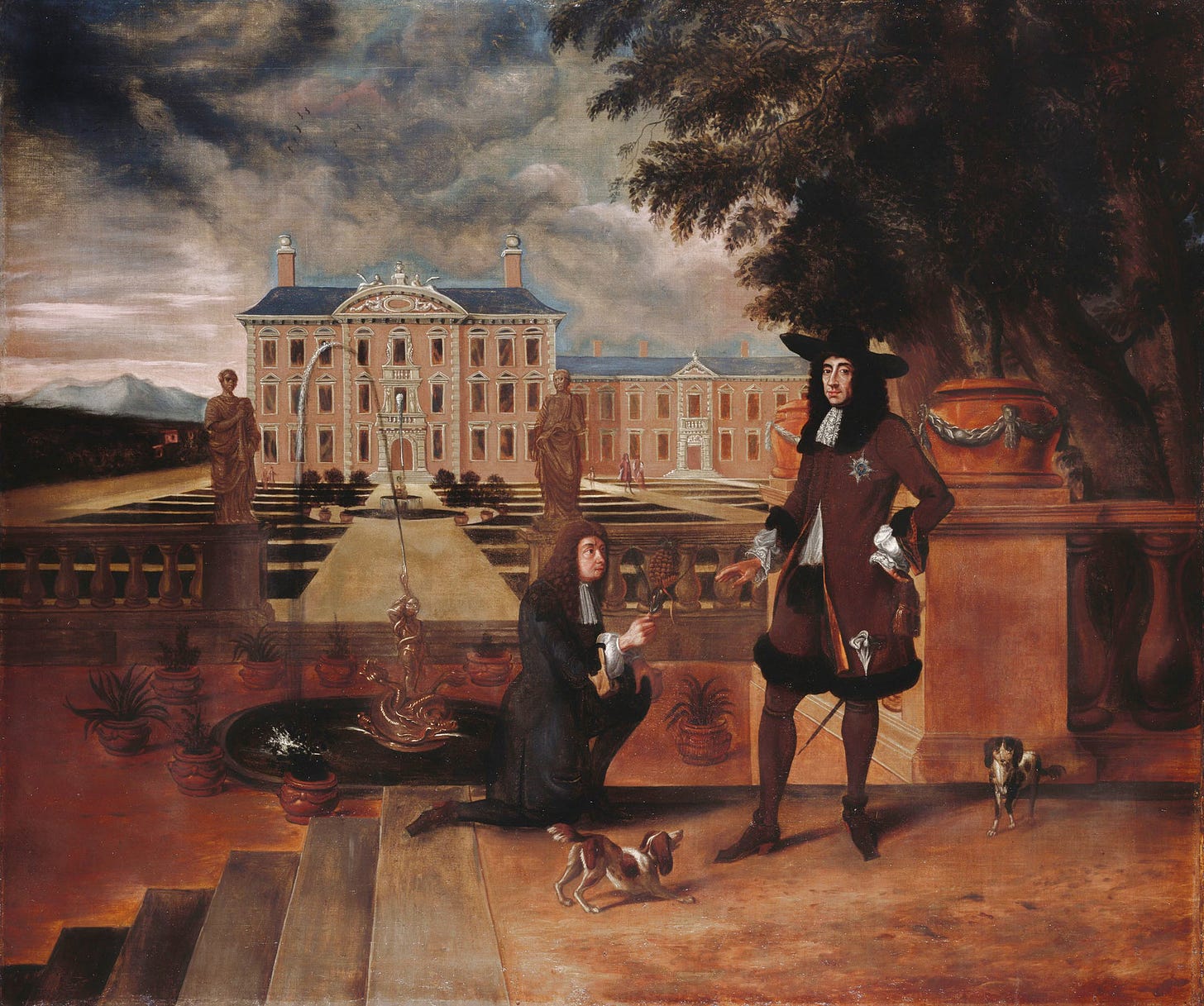

It is likely that a few edible pineapples made it across the Atlantic in the 16th century – harvested unripened – and that pineapple preserved in sugar was also transported, but these were not the same as the freshly picked fruit. Meanwhile cultivation spread rapidly to Africa and South Asia where the climatic conditions were perfect for the crop. Until well into the 17th century pineapples were, in Europe, objects of extraordinary rarity and fascination. So much so that the presentation of one to King Charles II of England was deemed worth of being recorded in a work of art:

We know that the king was generous in sharing his fruit, as the diarist John Evelyn recorded in his entry for 19th August 1668:

I saw the magnificent entry of the French Ambassador Colbert, received in the banqueting house. I had never seen a richer coach than that which he came in to Whitehall. Standing by his Majesty at dinner in the presence, there was of that rare fruit called the king-pine, growing in Barbadoes and the West Indies; the first of them I had ever seen. His Majesty having cut it up, was pleased to give me a piece off his own plate to taste of; but, in my opinion, it falls short of those ravishing varieties of deliciousness described in Captain Ligon’s history, and others; but possibly it might, or certainly was, much impaired in coming so far; it has yet a grateful acidity, but tastes more like the quince and melon than of any other fruit he mentions.

Evelyn’s disappointment was due to his pineapple being ripened on its long sea journey, rather than on a living plant. For Europeans to properly experience the fruit it had to be grown and ripened on the continent itself. This problem was finally solved in 1687 by Dutch art collector and horticulturalist Agnes Block (1629–1704), as an 1854 biography recounted:

She became particularly renowned for her extraordinary passion for flowers and plants, and her country estate Vijverhof, where in 1687 she brought the first pineapple in these regions to full perfection.

Obviously to celebrate this she had a picture painted of herself admiring her pineapple plant (can you see a trend emerging here?).

There were two ways of achieving the temperatures required to grow this wonderful fruit. The simplest, in terms of design and construction, was to create a pine pit which relied upon the warmth of fermenting manure, as William Speechly, the head gardener of Welbeck Abbey, explains:

The Pine-apple Plant requires more heat, and a greater degree of humidity than almost any other vegetable of the same tribe, which grow in our stoves or hot-houses.

The pit is generally from four to six feet deep, and from five to eight feet wide, being built with brick, and the sides plastered; a central passage is left, and on each side the beds for the plants. The beds are heated underneath with fermenting dung, tan, or leaves. A frame and lights, like those of a common hot-bed, are placed over the pit, so as to receive the full rays of the sun.

These pits required constant attention, and in time they were replaced with pine stoves – greenhouses heated with, you guessed it, stoves, and later hot water. It was using such a system that, sometime around 1714, Henry Telende, a Dutch gardener employed by Matthew Decker, a Dutch-born English merchant, economist and politician, finally grew the first pineapple in England. What did Decker do to celebrate? He had a painting done of it. Obviously.

The cost of production was insanely high for these early pineapples, it has be said as much as £80 each,6 when a labourer might earn £107 a year (so hundreds of thousands of pounds or dollars in today’s terms). This scarcity and exoticness lead to something called ‘pineapple mania’, with the fruit being represented in art (as you have seen) on fabrics, china and buildings. When Christopher Wren was deciding what to put on top of the south-west tower of St Paul’s Cathedral the choice was obvious – a massive golden pineapple.

The best place to have architectural pineapples was, of course, on the specialist hothouse you had constructed to grow them. The apogee of this is the Dunmore Pineapple House, built in 1761 by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore (1730–1809). Dunmore is perhaps better known as being the last British colonial governor of Virgina whose actions in 1775 and 1776 caused Southerners in general, and Virginians in particular, to solidify their opposition to British rule. But before all that he built the most amazing building in which to grow pineapples, and it stands to this day!

As the 18th century proceeded even though cultivation techniques improved pineapples were still astonishingly rare. William Cobbett (1763–1835) writing in Cottage Economy (1821) recalled that:

In my young days in London, I remember pine-apples being sold at a guinea each and sometimes more; but at that time they were extremely rare. I have seen them exhibited in the windows of fruiterers at two guineas each.

This was the equivalent of around £2,0008 ($2,700) in today’s terms and so if you couldn’t afford to buy a pineapple, you could rent one, as Cobbett explains:

I have heard of the same pine-apple being hired for a dozen different tables in London before it was at last sold to be eaten.9

How did this work? Simple – you would put your rented pineapple in the middle of your dinner table for the guests to gawp at, and admire your taste and discernment,10 then you’d send it back the next morning!

The introduction of the steamship in the 19th century enabled pineapples to be imported from the West Indies for consumption in Europe, ripening en route with little spoilage. While still luxuries, they became more widely accessible to the middle classes and with further improvements in shipping and refrigeration in the 20th century they became with in the reach of almost everyone.

As Jess will also be making pizza today, and to link back to my previous post, I’ll end by talking a little bit about that most contentious dish, the Hawaiian pizza. First off, it wasn’t concocted in Hawaii, rather in the Satellite Restaurant, Chatham, Ontario, Canada, in 1962. The inventor, Greek-born Sam Panopoulos, was messing around with new pizza ideas with his brothers and decided to put some tinned pineapple ('Hawaiian’ pineapple, hence the name of the pizza) together with some ham on a pizza. As Sam told the BBC in 2017:

We just put it on, just for the fun of it, see how it was going to taste. We were young in the business and we were doing a lot of experiments.

We tried it first, passed it to some customers, and a couple of months later, they're going crazy about it. So we put it on the menu.

To say that this creation has caused controversy is putting it mildly. In 2017 the president of Iceland, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, stated: “I would ban pineapple pizza if I could.” This caused Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, to retort: “I have a pineapple. I have a pizza. And I stand behind this delicious Southwestern Ontario creation.”

The debate rages on to this day. Some people love it. Some people hate it. Whatever your opinion it could not have existed without centuries of history.

Happy birthday for tomorrow, Jess!

Of course the Vikings had previously arrived in North America and occupied L’Anse aux Meadows around the year 1000, but they didn’t encounter pineapples.

Full transparency, Columbus’s journals from his second voyage have not survived, this is taken from a history written by Bartolomé de las Casas between 1527 and 1561, who did have access to them, and while this might be paraphrasing it is generally considered to be broadly accurate in terms of content.

It seems that Columbus is probably comparing the taste of the pine nuts to the taste of the fruit, but it isn’t clear.

Yes, I am aware of the account in Peter Martyr d’Anghiera’s De Orbe Novo of the King being presented with a pineapple, and there is contextual mention of him being delighted by tasting fruits, but it is not clear that he was actually eating the pineapple.

I would treat this figure with a degree of caution, it comes from secondary sources written in the early 19th century.

As I have mentioned in previous posts, equating historic sums to modern amounts is complex and there are various different methods. My personal view is that simply applying inflation under-calls it, and that the most effective approach in terms of understanding real value is to look at it in the context of average wages of the day, and compare those to their equivalents today.

I have seen reports that the sum was as high as £5,500!

Quite what state it was in at that point one can only speculate.

I can’t help but wonder that some were disappointed when they realised that they wouldn’t actually get to taste it…