A history of… pedestrianism (competitive walking)

Including some of the greatest athletes you've never heard of…

In my previous piece I explored the history of the pedometer and so it seemed natural to follow this up with the history of walking – or more specifically, the history of competitive walking, also known as pedestrianism. Well, actually, it is really a history of ultramarathons, the birth of athletics as a profession, and feats of endurance that frankly seem barely credible!

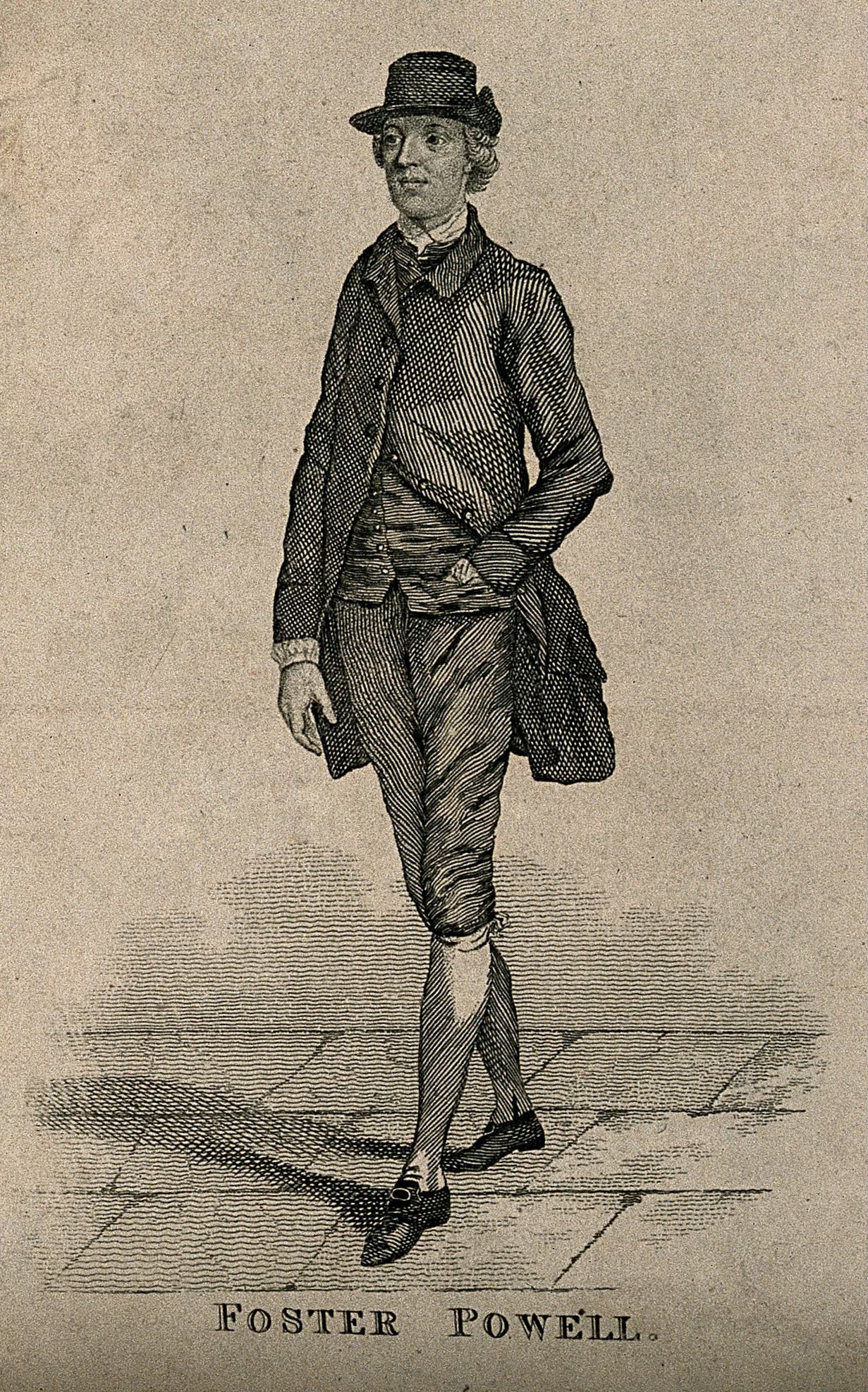

Foster Powell was born in Horsforth, Yorkshire in 1734 and until the age of 30 he was a fairly average legal clerk at the inns of court in London. Actually, somewhat less than average, for his fellow clerks considered him:

A milksop and a muff… a cadaverous-looking young fellow, thin and apparently weak. He was thought very little of, either in respect of his mental or physical qualities… a quiet, inoffensive lad, shy, and somewhat unsocial, with nothing in the faintest degree remarkable in him.

Then one day in 1764 something happened that caused his peers to make a radical reassessment of him. When asked by his co-workers how he intended to spend his Sunday he told them that he intended to walk to Windsor and back, a distance of some 50 miles. Now while he was very fond of taking Sunday walks, he hadn’t actually been planning to go that far, but worn down by their constant office jibes he said this to impress them. It didn’t work, or at least not initially:

This announcement provoked the jeers of his companions, thereupon for the moment he lost his temper and challenged any one of them to walk with him.

Two of them did, one dropping out after ten miles, the other after twenty. Powell completed his fifty miles and word of his feat soon began to spread throughout the inns. Walking became more than a means of gaining workplace kudos later that year when he was offered a prize of 20 guineas if he could walk 50 miles (80 km) in seven hours. Setting off down the Bath Road he beat this target, covering ten miles in the first hour alone! If you are a runner, or are interested in running, you will have realised quite how astonishing his pace was. In that first hour he did the equivalent of three, back-to-back, sub-20 minute 5ks, and then continued for another six hours after that. Furthermore he did this on a rough road, wearing leather shoes, and “a greatcoat and leather breeches”!

You have probably figured out by now that ‘walking’ in this context was a pretty loose term – Foster was running, or at least jogging, for much of that distance. Buoyed by this success – 20 guineas was a vast sum, more than a housekeeper could earn in a year – he took on various distance challenges, including running two miles in ten minutes. I can’t help but wonder that with a decent running track, some proper shoes and a couple of months of formal training and nutrition that perhaps he could have broken the four-minute mile record a couple of centuries early. Irrespective of my conjecture, he has been described as "the first English athlete of whom we have any record".

His greatest achievement was ‘walking’ from London to York, and back, in six days – a distance of some 400 miles (640 km) which he first did on 29th November 1773. The road was terrible, muddy and rutted by coach traffic. To cope with an agonising pain in his side he had to strap up his torso. He barely ate, subsisting on tea, water, toast and beer. And yet as he approached York on the third day he ran the last 17 miles, covering the distance in less than two hours! Having made it halfway he stopped at a pub for lunch, had a little nap, and turned around to head home. So famous had this challenge become, he had to disguise himself to avoid being mobbed when leaving the city, and when he arrived back in London, five days, eighteen hours and ten minutes after he started, a crowd of some 5,000 people joined him for his final steps.

This was the birth of the ‘six-day race’ which continues to this day as an ultramarathon challenge (the six-day limit was not random – it avoided running on the Sabbath). Foster went on to repeat this walk three more times, the last at the age of 58, in a time of five days, fifteen hours and fifteen minutes, beating his own record. A year later, possibly broken by his exertions, he died, and had a suitably pedestrian funeral:

[found dead] At his apartments in New Inn, Mr. Foster Powell, the celebrated pedestrian. His extraordinary feats of walking, by which he might, with proper management, have profited too much, never produced him enough to keep him above the reach of indigence, Poverty, which he ought always to have kept a day's march behind him, was his constant companion in his travels through life, even to the hour of death. In the afternoon of the 22nd his remains were brought for interment, agreeably to his own request, to St. Paul’s church yard. The funeral was characteristically a walking one, from New Inn, through Fleet Street, and up Ludgate Hill. The followers were twenty on foot, in black gowns, and after them came three mourning coaches, the attendants were all men of respectability.

In 2018, Australian Beau Miles released an enchanting film entitled ‘A mile an hour’ in which he runs a mile, you guessed it, every hour for 24 hours, using the remainder of the time to complete various jobs and projects. It turns out the idea is a pretty old one but the 19th-century version of it was way more extreme. On the first of July 1809 Captain Robert Barclay Allardice set off to walk 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours at Newmarket racecourse, covering one mile in each of those hours. He would walk two miles, back-to-back, over the turn of each hour so that he could get 90-minute breaks, but those were all the breaks that he had over more than 41 days. He completed his achievement, winning 1,000 guineas (establishing the true, historic, value of money is notoriously difficult, but this is around half a million pounds in today’s money).

The gentleman on Wednesday completed his arduous pedestrian undertaking, to walk a thousand miles in a thousand successive hours, at the rate of a mile in each and every hour. He had until four o’clock P.M. to finish his task; but he performed his last mile in the quarter of an hour after three, with perfect ease and great spirit, amidst an immense concourse of spectators.

For the last two days he appeared in higher spirits, and performed his walk with apparently more ease, and in shorter time, than he had done for some days before.

The multitude of people who resorted to the scene of action, in the course of the concluding days, was unprecedented. Not a bed could be procured on Tuesday night at Newmarket, Cambridge, or any of the towns and villages in the vicinity, and every horse and every species of vehicle was engaged.

More than half a century later, in 1864, 32-year-old Emma Sharp replicated the feat, walking 14,600 circuits of the Quarry Gap pub in Bradford. So much money had been wagered on the event that attempts were made to drug her food to stop her completing the challenge, and for the last two days she carried a pistol to protect herself (as if the walking alone wasn’t challenge enough!). Her achievement was soon surpassed by one of the most incredible people I have ever come across, Ada Anderson. Born in 1843, an actress and theatre manager, she was left all but penniless in 1877 when her husband died, so she thought that she would give endurance walking a go. Except those 90-minute breaks for the one-mile-an-hour walkers were too soft for her. That September she walked 1,000 half-miles in 1,000 half-hours – having no more than 20 minutes rest at a time for three weeks.

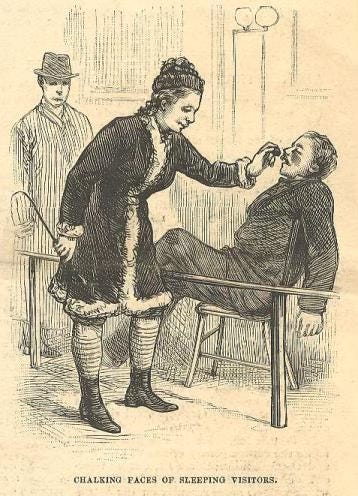

A few weeks later, in November 1877 she broke Barclay’s record by walking 1.25 miles every hour for 1,000 hours, and furthermore she started each walk at the start of the hour, not enjoying the ‘double breaks’ that Barclay had. Internationally famous, she made her US debut in December 1878 at Mozart Garden in Brooklyn walking 2,700 quarter-miles in 2,700 quarter-hours. This meant that over the course of 28 days she slept for no more than nine minutes at a time! Professional walkers said that the feat was impossible for a man, let alone for a woman, and yet under the constant eyes of judges and vast crowds she completed it, and completed it in style. Ada didn’t just walk, she sang as she did so and played the piano during breaks. She also enjoyed drawing on the faces of spectators who had fallen asleep!

The end of her walk was a thrilling event, as the New York Times recorded:

During the entire evening Mms. Anderson was sustained by the most intense and hardly-to-be suppressed excitement. At times she walked at a tremendous pace, almost running around the track, with pale face and clenched teeth.

As the bell rang again, calling her to the track for the last time, she darted from the little doorway before its sound had ceased, and started off at a terrific pace, determined to beat 2:40, the best time recorded by one of her male friends some days since. The band tried to play “Don’t Get Weary” but its loudest discords were drowned out by the deafening cheers and yells that were kept up during the next three minutes. The women yelled with the men, and became frantic in their excitement. The air was white with the fluttering of handkerchiefs and the scene presented has seldom been equalled in Brooklyn.

The pace was a run rather than a walk, and as she finished she was lifted into a chair on the platform in the last stages of exhaustion. The frenzied cheering was hushed for a moment, as the scorer announced that the quarter was the fastest of the entire walk in 2:37 ¾ , and then it was renewed, louder, if possible, than before.

To my mind these ‘pedestrians’ were elite athletes, on a par with the very best competing today. If this seems somewhat hyperbolic then I’d like to end with a few words about George Littlewood, also known as ‘The Sheffield Flyer’. George took part in all kinds of different races, but his specialty was the six-day race that had been invented by Foster Powell. Between 26 November and 1 December 1888 he covered 623 miles 1,320 yards (over 1,000 kilometres), setting a world record that wasn’t beaten until 1984, 96 years later! It is still the British record!

Littlewood also set a six-day record for race-walking (you may have seen this at the Olympics – unlike running, the athlete’s back toe cannot leave the ground until the heel of the front foot has touched it) in 1882 of 531 miles (854 kilometres) which remains unbroken to this day!

All of this discussion of walking has been somewhat exhausting for me and I could do with a drink, so in my next piece I will be looking at the history of beer.