For the vast majority of human history one thing that meant the difference between life and death was a person’s ability to make fire. Fire was essential for warmth, protection, cooking, tempering stones and melting metals to make tools. Humanity’s history of using fire pre-dates what we consider to be the emergence of modern humans. The earliest evidence of fire-use by hominids ranges from 1.7 to 2.0 million years ago. Archaeological traces of the use of controlled fire to cook food date back 780,000 years (though some studies suggest that cooking is significantly older even than that – 1.8 million years ago). Three-hundred-thousand-year-old fire-treated flints (the heating of the stone makes it easier to flake and fashion into tools) have also been found – our relationship with fire is longer than I can really comprehend. Of course to use fire, one has to be able to make it, so this piece will explore how our methods of making fire have evolved over time.

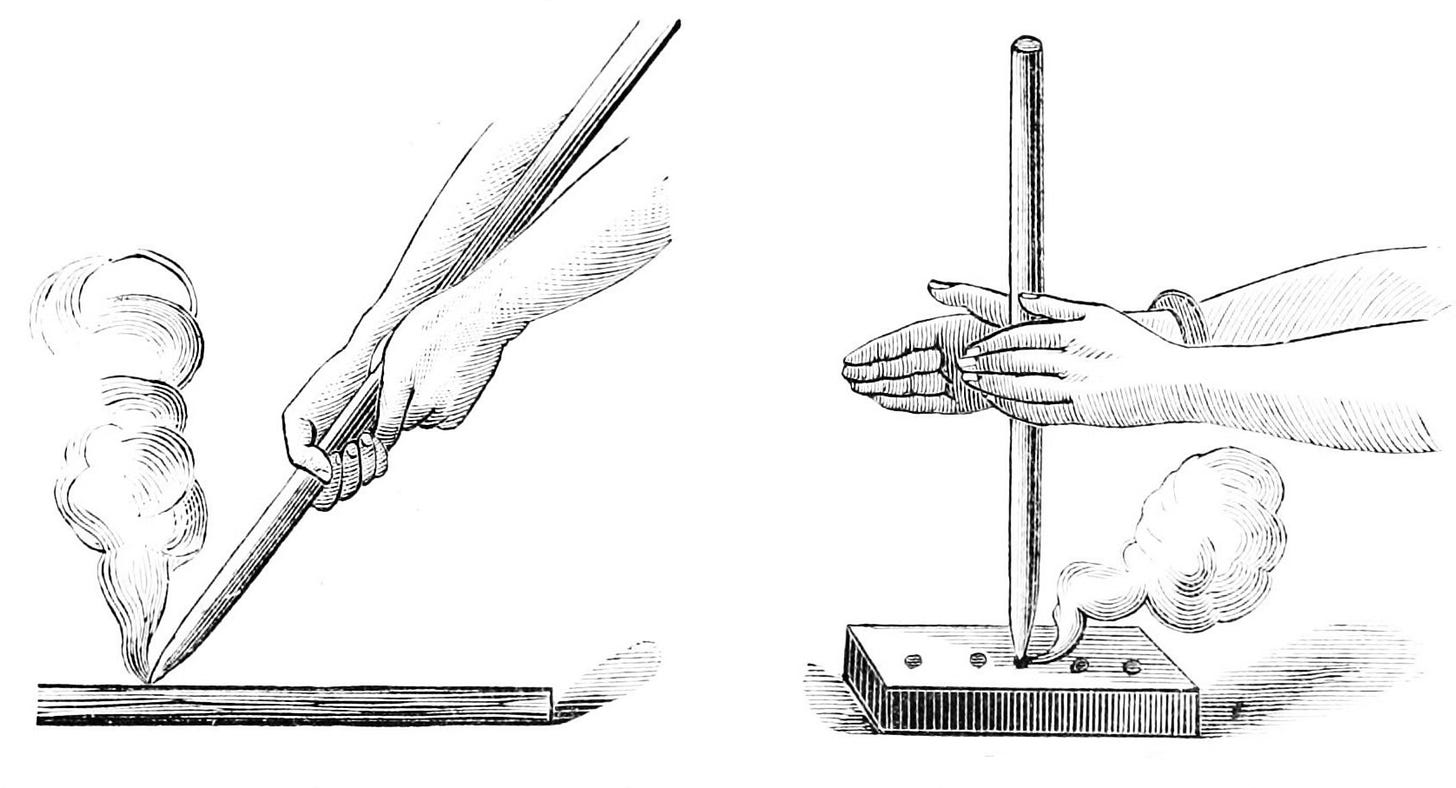

The earliest method of making fire – one still practised by indigenous tribes today – involved the use of friction. As you probably know, if you rub things together, they get hot, and so if you rub two pieces of wood together long enough and hard enough it is possible to get it to reach the autoignition temperature of wood (300–482 °C / 572–900 °F, depending upon the wood). The most common way of doing this is by using a fire drill. A straight, hard stick is placed vertically in a notch and rubbed backwards and forwards with the hands (or sometimes using a bow) until it heats sufficiently to create a small, glowing coal which can be used to ignite tinder. An alternative method is the fire plough whereby a stick is rubbed back and forth along a long notch in the wood. Having been taught this method of fire making on an outdoors skills course many years ago I can tell you that it takes a significant amount of time and effort (I failed totally to make fire, but it was by no means easy even for my instructor). The materials used need to be kept very dry, which can be challenging in tropical environments.

An easier way to make an initial spark, for those who had access to the materials, is to strike together flint and pyrite (better known as ‘fool’s gold’). The impact flakes off tiny fragments of the iron pyrite which oxidises in the air, heating rapidly to create glowing sparks. Ötzi, also known as ‘The Iceman’, the 5,400 year-old mummy I mentioned in my piece on pockets had a fire-making kit that contained flint, pyrite, a dozen different plants to use as tinder and the fungus Fomes fomentarius, also known as tinder fungus, which is used for firelighting to this day.

The coming of the Iron Age led to the replacement of pyrite with a piece of iron, often formed into a D shape that could be looped over a couple of fingers to make for easy striking. This approach to making fire was the one most commonly used for more than 3,000 years, right up to the 19th century. The main advancement over that time was the creation of the tinder box.

Your tinderbox would generally contain a steel striker (though this could be carried separately), a piece of flint, some tinder, and often would have a candle on the top. The most common tinder was charcloth – a small piece of material that had been heated in almost airtight conditions (such as stuffed in a tight tin and left heating on a fire) which caused them to undergo thermal decomposition (also known as pyrolysis). This process results in something that is almost pure carbon, which is easy to light and create a hot ember.

To use a tinderbox you would open it (obviously), arrange your charcloth in the bottom, strike the flint to create sparks, puff on the glowing ember and use that to light a sulphur-tipped taper which was then used to light the candle on the top of the box. The lid would then be put back on, snuffing out the tinder so that it could be reused, and the candle then used, in association with additional tapers, to light the things that you needed lighting. If this sounds like an involved process, it was – a skilled person could get the candle lit in under a minute, but it would often take a fair bit longer.

This may seem like an odd comparison to make, but tinderboxes were, for centuries, somewhat like smartphones are today. Everyone would have one, you would use them multiple times a day (to light candles, fires, stoves, pipes etc.) and you would generally carry one with you when out and about. As with smartphones, if you had more money to spend you could get a fancier tinderbox. Tinder pistols used a similar flightlock mechanism to guns, whereby pulling the trigger would release a shower of sparks into a small tinder chamber. This was both easier to use than a regular box and almost certainly gave the user the opportunity to show off their wealth.

The somewhat unwieldy nature of tinderboxes drove 18th and 19th-century European inventors to come up with other solutions to make fire more easily. One such solution, which never gained widespread use, was the fire piston. Scientists had observed that if one compressed air in a tube it gets hot (you have have noticed this happening by the warmth of a pump when inflating a bicycle tyre). They discovered that if one placed a piece of tinder at the bottom of a sealed tube and slammed a tightly fitting cylinder into said tube very hard and very fast the compressed air would heat up so much that the tinder would ignite. While fire pistons didn’t take off in Europe, they had, amazingly, already been invented and used in south-east Asia for a couple of thousand years. The Austronesian people made them out of bamboo and bone and it was these devices that inspired Rudolf Diesel to invent the diesel engine (in which the fuel is ignited by the temperature increase caused by pressure) in 1892!

You may, like me, have used a magnifying glass to burn holes in pieces of paper using the sun’s rays as a child and if so you were replicating another ancient form of fire making. Such burning glasses were used in both Ancient Greece and Roman – Pliny the Elder recounts that light magnified through glass jars could be used to cauterise wounds, and there is a myth that the great Archimedes used concave mirrors to ignite the Roman fleet that attacked Syracuse. More tangible evidence comes from the 424 BC play The Clouds by Aristophanes:

Strepsiades. Have you ever seen a beautiful, transparent stone at the druggists’, with which you may kindle fire?

The most significant development in the history of fire making came about with the invention of the match. The first matches were invented in 1805 by Jean Chancel in Paris, and I think it is fair to say that they were somewhat less practical than the ones we use today. Chancel’s matches had a head containing potassium charlotte, sulphur, gum arabic and sugar on a wooden stick and they were ignited by dipping them into a small asbestos bottle of sulphuric acid. They were expensive, messy and fairly dangerous to use so never really caught on. Things were improved slightly by the invention of the ‘Promethean match’ by Samuel Jones in London in 1828. These consisted of small glass capsules containing sulphuric acid whose outsides were coated in potassium chloride, the whole being wrapped in paper. To light them you, err, had to crush the thing with a pair of pliers and wave it around until it caught light!

The game-changer was the invention of the friction match first successfully produced by John Walker in 1828. These sticks were coated with sulphur, potash and a few other chemicals and when pulled through the fold of sandpaper handily included in the box the friction would cause them to light – no more messing around with sulphuric acid to get your fire going! Things got better still with the use of white phosphorus in the matches created by the Frenchman Charles Sauria in 1830 and variations on his approach continued up until 1890. There was a problem though; while phosphorus was great for matches, it was pretty dire for the workers – mostly women – who had to make them. Exposure to the phosphorus vapours caused ‘phossy jaw’, the weakening and eventual destruction through necrosis of the bones in the jaw and the associated loss of teeth. White phosphorus was eventually replaced by red, and the final step in the evolution of the match was the invention of the safety match. These basically work by separating the chemicals from a friction match between the match and the striking paper on the side of the box, and adding in some powdered glass to create friction.

Finally let me turn to the most commonly used means of making fire in the 21st century, the lighter – and as with the match, this is a comparatively late invention. In 1823 the German chemist Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner observed that when hydrogen was blown across a fine mesh of platinum (called a platinum sponge) the metal would catalyse the oxidation of the hydrogen and heat up to the extent that the hydrogen would catch on fire. He created a bottle that would hold a piece of zinc and sulphuric acid (which when combined would generate hydrogen) with a valve control to release the gas over the platinum, creating a burning flame.

Despite this being a far cry from the sort of thing one could easily slip into one’s pocket it was so much easier than the other methods of fire making at the time that these lighters sold over million units in the 1820s! The invention of ferrocerium (the ‘flint’ in the lighter which is actually a combination of a variety of metals) enabled the development of the modern lighter. Initially, as with Zippo lighters today, the sparks ignited wicks soaked in petrochemicals but today they mostly employ liquified butane.

Lighters today are so cheap and so ubiquitous that they are literally disposable, but hopefully this brief history will make you appreciate how easily you can make fire compared with the rest of human history!