(A quick note to introduce myself. My name is Paul and I have been working with Andrew on various projects for almost 20 years. We have co-authored a numbers-related book together and published a book I wrote about cats, amongst many other things! My historical interests range from the very narrow (the history of Port Meadow in Oxford, for example) to the very broad, and it is into this latter category that these pieces fall. I find myself constantly wondering about how the things that we encounter in daily life, from ketchup to playing cards, came to be a part of our modern world. Researching their history I find stories that are, I hope you will agree, both unexpected and fascinating.)

Humans have been wearing clothes for a long time. It is difficult to know exactly how long, because, unlike bones and flint tools, clothing tends to rot away leaving nothing for us to find. We can, though, get a pretty good sense of our clothing history from looking at a louse.

The human body louse, Pediculus humanus humanus, to be exact – a distinct species that only lives on humans. As this louse can only survive for a couple of hours away from the shelter provided by clothing we must have been wearing clothing for at least as long as this species has existed. The differences between the DNA of the human body louse and its sibling species, the human head louse, Pediculus humanus capitis provide a genetic ‘clock’ which suggests that these two species diverged from a common ancestor around 170,000 years ago. Recent archeological evidence supports dates in the same ballpark. In 2021, 120,000-year-old bone tools for skinning and preparing furs were found in Morocco.

While clothing is ancient, pockets (as we know them) are remarkably recent. People have, of course, always had a need to carry things but for much of human history this was in the form of a separate bag. Ötzi (also known as ‘The Iceman’) – a 5,300-year-old mummy found frozen in an Austrian glacier in 1991 – was found wearing a belt with a pouch sewn onto it (the pouch contained a fascinating collection of useful items including a scraper, drill, flint flake, bone awl, and a dried tinder fungus).

The concept of a separate pouch serving the function of today’s pockets continued well into the 17th century (the word ‘pocket’ first appears in Middle English, and is taken from a Norman diminutive of Old French pouque, meaning bag). Because such pouches were obvious targets for thieves it made sense for them to be worn under layers of clothing, and in 13th century Europe slits, called fitchets, were cut in these clothes to enable easy access. These slits looked somewhat like modern pockets, but the pouch they were accessing was not an integrated part of the garment.

Some men in the 16th century couldn’t conceal pouches under their clothing because they wore hose, which was, as the Venetian engraver Cesare Vecellio wrote, “so closely fitted that they showed almost all their muscles, as if they were completely naked”. What did they use instead of pockets? The 1613 book The Treasurie of Auncient and Moderne Times explains:

..they hadde a large and ample Cod-piece, which came uppe with two wings, and so were fastned to eyther side with two Pointes. In this wide roome, they had Linnen bagges, tied with like Points to the inside, betweene the Shirte and Cod-piece. This serued as the receipt for Pursse, Hand-kerchers, Apples, Plummes, Peares, Orenges, and other fruits.

I can’t imagine that eating an apple that had been languishing in my codpiece all day would have been hugely pleasant, and the Treasurie goes on to make a similar point:

…did it not seem verie Inciuill [incivil], that sitting at the Table, hee should make a present of such, preserued (for som time) in so sweet a Closet, euen as now adaies, some (as mannerly) vse the like out of their Pockets?… Surely, in my poore opinion, the fashion of Pockets made in the Doublet Sleeue, or in the hose, is much more honest and commendable?

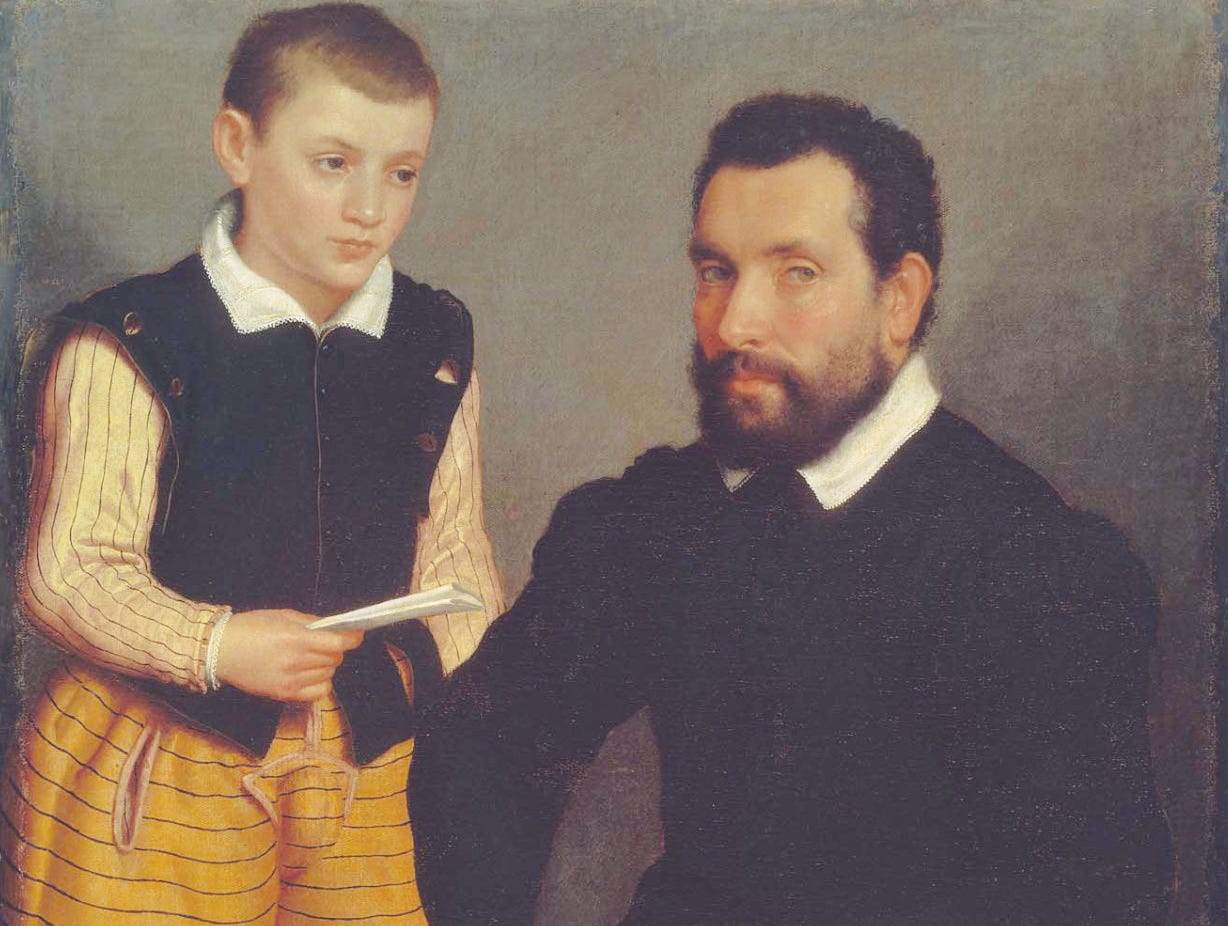

The move towards more voluminous clothing over the course of the 16th century meant that modern pockets could be introduced. A painting of Count Alborghetti and his son made around 1550 by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Moroni clearly shows a neatly lined pocket in the boy’s hose, one of the earliest representations in art.

The existence of pockets – be they pouches or parts of clothing – gave rise to a particular type of criminal, the pickpocket. You may be familiar with Fagin’s school for pickpockets in Oliver Twist and they were in operation for hundreds of years before the birth of Charles Dickens. William Fleetwood was the Recorder (the most senior judge) of the City of London and was “always in hot pursuit of pickpockets and conny-catchers of all kinds”. In 1585 he wrote about a school run by a 16th-century Fagin:

One Wotton, a gentleman born, and sometime a merchant man of good credit, who falling by time into decay, kept an alehouse at Smart’s Key, near Billingsgate, and after for some misdemeanor being put down, he reared up a new trade of life, and in the same house he procured all the cutpurses about this city to repair to his same house. There was a schoolhouse set up to learn young boys to cut purses. There were hung up two devices, the one was a pocket, the other was a purse. The pocket had in it certain counters, and was hung about with hawk’s bells, and over the top did hang a little sacring bell; and he that could take out a counter without any noise was allowed to be a public foyster, and he that could take a piece of silver out of the purse, without the noise of any of the bells, he was adjudged a judicial nypper. Note, that a foyster is a pick-pocket, and a nypper is termed a pickpurse, or a cutpurse.

Clearly there were two different types of thief: ‘Nips’, who used a knife to cut purses free, and ‘Foists’ who relied solely upon their prestidigitation to steal a purse (or simply empty it of its contents). Foists thought that their work was significantly more skilled, and it is said, they refused to even cut their food with a knife lest they be mistaken for a pathetic Nip!

The contents of 16th-century pockets were also somewhat different to those of today. In 1546 Stephen Gardiner, the Bishop of Winchester, wrote of:

…how a German, rude and gross, when he should have [delivered his] letters to the French king put his hand in his pocket to take out his letters and first pulled out, instead of letters, a piece of cheese and then pulled out a piece of bacon and then a lump of bread, and finally his letters.

Given its capacity it seems likely that this pocket was more of a separate pouch, rather than part of a garment. Nonetheless it probably wouldn’t have been the most hygienic place to keep one’s lunch and it is hard to imagine that when those letters were finally presented to the King of France they were in pristine condition!

An interesting facet of this history of pockets is the disparity of pockets between the genders. For a fairly brief period of time in the 16th and 17th centuries there was something of an equality of pockets in men’s and women’s dress. Clothing for both was sufficiently baggy that it could conceal a pocket, though for women these still tended to be separate pouches, attached to a belt under her dress. This is how it was possible for Lucy Locket to lose her pocket in the nursery rhyme:

Lucy Locket lost her pocket,

Kitty Fisher found it;

Not a penny was there in it,

Only ribbon round it.

While Lucy Locket had nothing in her pocket that wasn’t the case for most women of the period, as an advert seeking the return of a pair of lost pockets from Mist’s Weekly Journal in 1725 demonstrates:

D[r]opp'd between St. Sepulchres church and Salisbury court in fleet-street, going down fleet-lane, and crossing the bridge, a pair of white fustian pockets, in which was a silver purse, work’d with scarlet and green S.S. In the purse there was 5 or 6 shillings in money; a ring with a death at length in black enamell’d, wrapp’d in a piece of paper; a silver tooth pick case; 2 cambrick handkerchiefs, one mark’d E.M. the other E5D; a small knife; a key and pair of gloves, and a steel thimble. &c. If the person who took them up will bring them to mr. peachy’s at the black boy in the o’d baily, he shall receive a guinea reward, ann no questions ask’d.

Later in the 18th century however women’s clothing became more figure hugging and, as with the hose a few centuries earlier, pockets became far harder to conceal. It was said that:

[women] had four external bulges already — two breasts and two hips — and a money pocket inside their dress would make an ungainly fifth

Pockets moved out from underneath clothing and became reticules, small bags often made of silk or netting that could be carried hung from the wrist or arm. Unlike older pockets these reticules had barely enough space for a handkerchief, a few coins, and perhaps a pin or two.

Increasing women’s emancipation over the course of the 19th and into the 20th century had an impact upon pockets. In 1881 the Rational Dress Society was formed in London with the objective of promoting more practical, and pocket-friendly, clothing. One result of the changing fashion was that women had pockets that they could put their hands in! This may seem to be uncontentious today but it has a significant impact upon both their confidence and how they were perceived. As The Graphic wrote in 1894:

The pockets of the ‘New Woman,’ admirably useful as they are, seem likely to prove her new fetish, to stand her instead of blushes and shyness and embarrassment, for who can be any of these things while she stands with her hands in her pockets?

The extent to which the placing of hands pockets became associated with emancipation can be readily seen in the poster for Charles Hoyt’s 1898 play A Contented Woman, where three suffragettes adopt this stance.

Fashions come and fashions go. Today women’s clothing has far fewer pockets than men’s, and even these can be fake, rather than functional. The designer Christian Dior is at least partly to blame for this, as he declared in 1954 “Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration”.

Those functional pockets that do exist are usually significantly smaller in women’s clothing than in men’s. A 2018 study of the 20 most popular brands of blue jeans in the USA found that women’s pockets were 48 per cent shorter and 6.5 per cent narrower than men’s. As the history of pockets has hopefully shown, fashions do change over time and perhaps in the not-too-distant future everyone will have access to practical pockets. It is even possible that massive, fruit-storing codpieces become trendy again. But let’s hope not…

Enjoyed this! Thank you Paul.

A lovely example of why the history of daily life is so fascinating!