There are some things that we encounter in modern life that are so familiar, so ubiquitous, that they become part of the scenery of our existence. We never wonder why they are there, and only notice their absence.

Tomato ketchup is, for me, one of those things – or catsup, if you prefer. Until recently I never stopped to wonder why it was that every fast-food restaurant in the world (and many ‘slower’ restaurants as well) should have a sauce, made of tomatoes, readily available for anyone who wanted to splurge it onto their food. When did this start? Why tomatoes? So I decided to do a bit of digging into the history of tomato ketchup…

It is probably worth starting with a consideration of the purpose of tomato ketchup. It is a simple, quick and cheap way to add flavour and moisture to food that otherwise might be somewhat dry and bland – such as French fries. Humans have been using sauces to this effect for thousands of years. The Romans, famously, had garum, a fish sauce made from a combination of entrails and salt, left in the sun to ferment and then squeezed to release the liquid. This may sound utterly disgusting to the modern palate, but it seemingly was a great way to add umami to food.

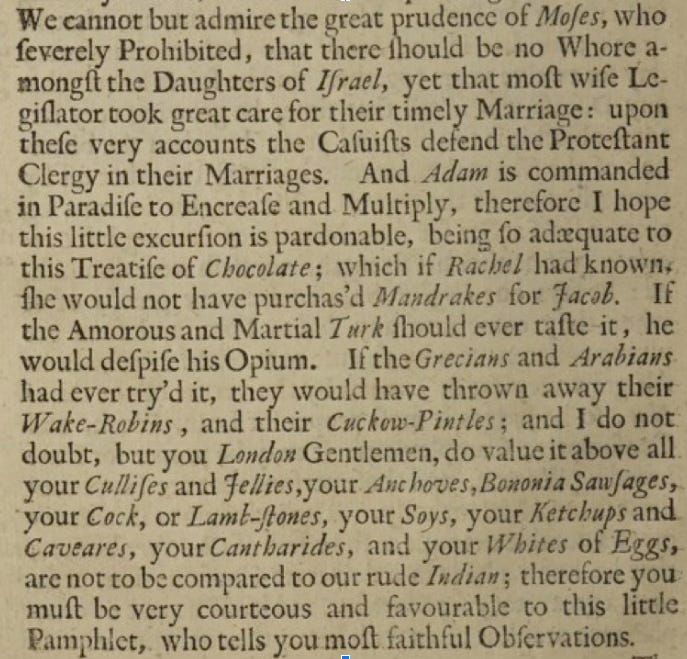

It is probably from a similar fish sauce that we get the modern word ‘ketchup’ (there is quite some debate about the etymology of the word). Kôe-chiap (or kê-chiap) is the Chinese name for a brine of pickled fish (or shellfish) and it seems likely that the British took both the name and the idea for a savoury sauce back home sometime in the 17th century. The earliest known usage of the word ‘ketchup’ in English dates from 1682 book by John Chamberlayne entitled The natural history of coffee, thee, chocolate, tobacco.1 Why is ketchup mentioned in a book about coffee, thee (tea), chocolate and tobacco? Well, as you can see from the extract below it is mentioned in a somewhat odd digression about how amazing chocolate is, both generally, and, err, as a means of improving men’s fertility.

That Chamberlayne uses the word ketchup in this manner suggests that it is in common parlance in 1682, strong evidence that ketchup had been around in Britain for a reasonable period of time.

As an aside I have to say that this brief book is one of the oddest that I have read. The page referenced above begins with a discussion of the paradox that men endeavouring to avoid “nocturnal emissions” (which are sinful) can succumb to fornication (clearly also sinful). I am at something of a loss to explain how this subject matter aligns with the stated contents of the book, though to be fair the author does admit himself that this is something of a digression!

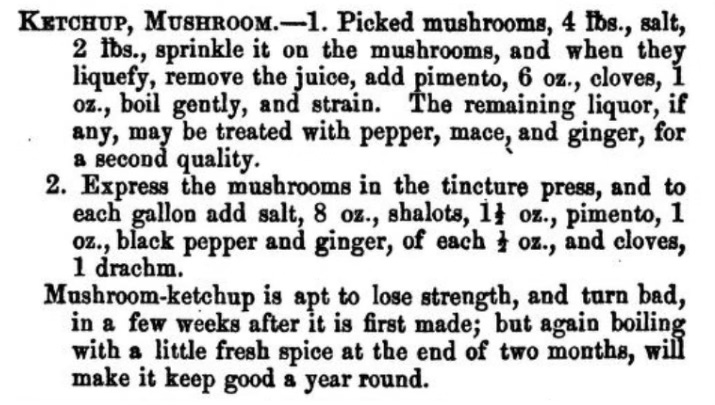

Seventeenth-century ketchup was not made of tomatoes; rather it was made of mushrooms (or sometimes walnuts). While not quite as disgusting sounding as a sauce made from fermented fish guts, the ketchup of that time does not sound particularly appetising, as this recipe shows:

Personally, if I find that a pack of mushrooms has started to liquify I think “Urggh!” and throw them away. I don’t think “Great! Time to make some ketchup!” – but clearly tastes differ both over time and between individuals.

A more detailed recipe (which includes anchovies) can be found in Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife from 1732:2

To make English Katchup.

TAKE a wide mouth’d Bottle, put therein a Pint of the best White-wine Vinegar; then put in ten or twelve Cloves of Eschalot, peeled and just bruised; then take a quarter of a Pint of the best Langoon White-wine; boil it a little, and put to it twelve or fourteen Anchovies washed and shred, and dissolve them in the Wine, and when cold put them in the Bottle; then take a quarter of a Pint more of White-wine, and put in it Mace, Ginger sliced, a few Cloves, a Spoonful of whole Pepper just bruised; let them boil all a little; when near covered, slice in almost a whole Nutmeg, and thyme Lemon peel, and likewise put in two or three Spoonfuls of Horseradish; then stop it close, and for a Week shake it once or twice a Day, then use it; 'tis good to put into Fish Sauce, or any savoury Dish or Meat; you may add to it the clear Liquor that comes from Mushrooms.

Mushrooms were swapped out for tomatoes most likely sometime early in the 19th century – the earliest known recipe for tomato ketchup dates from 1812. Anchovies were carried over as part of the recipe from the mushroom version, as this example from 1817 shows, but dropped out of use sometime in the 1850s:

Gather a gallon of fine, red, and full ripe tomatas; mash them with one pound of salt.

Let them rest for three days, press off the juice, and to each quart add a quarter of a pound of anchovies, two ounces of shallots, and an ounce of ground black pepper.

Boil up together for half an hour, strain through a sieve, and put to it the following spices; a quarter of an ounce of mace, the same of allspice and ginger, half an ounce of nutmeg, a drachm of coriander seed, and half a drachm of cochineal.

Pound all together; let them simmer gently for twenty minutes, and strain through a bag: when cold, bottle it, adding to each bottle a wineglass of brandy. It will keep for seven years.

(That does seem like quite a lot of brandy to add to each bottle, but these were more like demijohns than modern ketchup bottles.)

The invention of ketchup led to a significant increase in the consumption of tomatoes – a bottled preserve is much easier to transport and store than a soft fruit that spoils easily. It has also been claimed that it helped overcome the reticence of the British to eat tomatoes. This is said to stem from the fact that the acid in the tomatoes would slightly dissolve the surface of pewter plates and cause lead poisoning in the diner – but this could well be purely conjecture. Lead poisoning takes a fairly long time to build up and adversely affect the health of the victim and it seems unlikely that such a causal link would have been obvious. Maybe they just didn’t like tomatoes very much.

Initially bottled tomato ketchup was a cottage industry – farmers would make it for sale in their local areas – but that all changed when a man named Jonas Yerkes came along. He saw the potential of ketchup in a way that no one else before had done, and by 1837 was distributing bottle ketchup nationally – making it one of the very first pre-packaged foodstuffs to be sold at scale.

The birth of modern ketchup can be dated to 1876 when Henry James Heinz started selling Heinz Tomato Ketchup. This wasn’t his first attempt at selling bottle condiments – he originally started in 1869 selling horseradish, pickles and sauerkraut, but that business went bust in 1875. Tomato ketchup, however, turned out to be his goldmine. One of his key innovations was to increase the amount of sugar and vinegar in the recipe. This served both to improve the flavour and to increase its shelf life. In case you are interested, the “57 Varieties” slogan was introduced by Heinz in 1896 despite the fact that they were already selling more than 60 products. He chose 57 because his lucky number was 5 and his wife’s lucky number was 7.

The ketchup of the late 19th century was somewhat different to that sold today. It was typically made from unripened tomatoes, which meant that the sauce lacked flavour and also, due to the lower levels of pectin in the unripe fruit, was much more watery than the ketchup you are familiar with. It also needed, in addition to the sugar and vinegar, an additive called sodium benzoate to keep the product fresh.

Concerns about the use of sodium benzoate in the early 20th century are what ultimately led to the creation of the ketchup sold today. In order to create a product that would last without the use of this preservative, unripened tomatoes were replaced with ripened ones, and more sugar and vinegar were added. This worked out very well for the H.J. Heinz company – they produce more than 650 million bottles of ketchup a year and command 60 per cent of the ketchup market in the USA (in the UK it is more than 80 per cent).

Globally ketchup is big business. Really big business. I must confess that I was astonished to find out just how big. In 2024 ketchup sales are forecast to exceed 37 billion dollars, with 15 million tonnes of the sauce sold – or around 1.9 kilos of ketchup for every human being on the planet. Ketchup consumption, like most things, is not evenly distributed, however. Americans consume over 5 kilos (11 pounds) per person per year. That equates to around 1.5 serving sachets’ worth of ketchup per day!

Did you know that there are official grades of ketchup? Well, there are! The gradings are ‘Fancy’ (the highest) followed by ‘Extra Standard’ and ‘Standard’. These grade are determined by the specific gravity (think ‘gloopiness’) and hence the amount of tomato solids they contain – the higher the better.

That then leaves the question of why ketchup is so popular, so much more popular than other condiments. The answer is generally said to be because ketchup is ‘the perfect food’ – it provides the consumer with all of five of the different types of taste we are able to experience: salt, sweet, sour, bitter and umami, and it does so in a cheap and readily available manner.

All of this talk of food has made me hungry, so I'm off to get some French fries. With tomato ketchup, of course…

Actually the full title is The natural history of coffee, thee, chocolate, tobacco : in four several sections; with a tract of elder and juniper-berries, shewing how useful they may be in our coffee-houses: and also the way of making mum, with some remarks upon that liquor / Collected from the writings of the best physicians, and modern travellers, which is a bit of a mouthful.

Actually, its full title was: The compleat housewife: or, Accomplish’d gentlewoman’s companion: being a collection of several hundred of the most approved receipts, in cookery, pastry, confectionary, preserving, pickles, cakes, creams, jellies, made wines, cordials. And also bills of fare for every month in the year. To which is added, a collection of near two hundred family receipts of medicines; viz. drinks, syrups, salves, ointments, and many other things of sovereign and approved efficacy in most distempers, pains, aches, wounds, sores, &c. never before made publick in these parts; fit either for private families, or such publick-spirited gentlewomen as would be beneficent to their poor neighbors. Which is, again, a bit of a mouthful. Clearly 17th and 18th century publishers thought it important to cram as much as possible into the title of their books – not dissimilar to the keyword stuffers of today’s Amazon listings, perhaps.