A history of… hotels (Part 3)

Indoor toilets arrived on the scene really quite late…

In my previous two pieces I explored how, over time, commercial accommodation evolved over the course of a couple of thousand years. But even as we move into the late 18th century there wasn’t really anything that akin to what we consider to be a hotel now.

People of that era would typically stay in coaching inns and taverns, usually family-run, where the facilities were pretty basic and you could often end up sharing a bedroom with strangers. Even well into the 19th century such conditions prevailed, as shown by the account Charles Dickens gave of The Great White Horse in Ipswich (which is a real inn that survives to this day)1 in The Pickwick Papers (1837), that was almost certainly based upon first-hand experience:

In the main street of Ipswich, on the left-hand side of the way, a short distance after you have passed through the open space fronting the Town Hall, stands an inn known far and wide by the appellation of the Great White Horse, rendered the more conspicuous by a stone statue of some rampacious animal with flowing mane and tail, distantly resembling an insane cart-horse, which is elevated above the principal door. The Great White Horse is famous in the neighbourhood, in the same degree as a prize ox, or a county-paper-chronicled turnip, or unwieldy pig—for its enormous size. Never was such labyrinths of uncarpeted passages, such clusters of mouldy, ill-lighted rooms, such huge numbers of small dens for eating or sleeping in, beneath any one roof, as are collected together between the four walls of the Great White Horse at Ipswich.

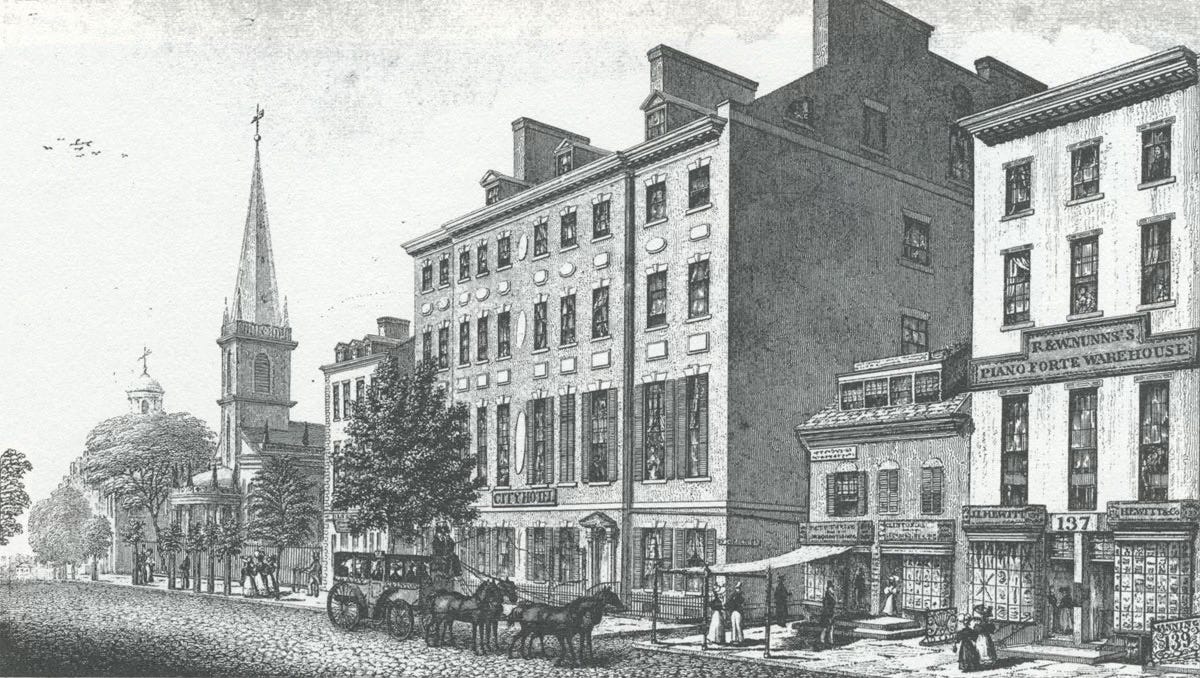

Improvements to the industry had, however, been afoot for a while. 1769 saw the opening of the Royal Clarence Hotel2 in Exeter, described in a 1770 newspaper advertisement as a “New Coffee-house, Inn, and Tavern, Or, The Hotel, In St. Peter’s Church-yard, Exeter.”, purpose-built and offering a much higher standard of accommodation than establishments such as The Great White Horse. It was still very-much an inn-scale enterprise, and we need to look to the USA to find the first truly large-scale hotel. The City Hotel opened in New York in 1794 with 137 rooms spread over five stories. An 1828 guide book described it in gushing terms:

City Hotel, [operated] by Chester Jennings, is the chief place of resort, and … the loftiest edifice of that kind in the city, containing more than one hundred large and small parlours and lodging-rooms, besides the City Assembly Room, chiefly used for Concerts and Balls. The rooms appropriated for private families, parlours, and dining rooms are superbly fitted up, and constantly occupied by respectable strangers. Extensive additions have recently been made to this establishment. The principal Book stores and Libraries are in the vicinity. Prices, over two days, $1.50 per day, $10 per week,3 $416 per year—Board only, $5.50 per week, dinner only, $3.50 per week.

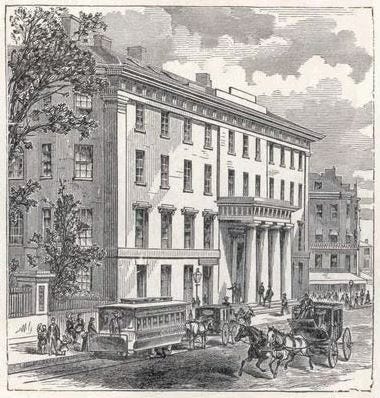

The year after that review was written, 1829, saw the opening of Tremont House in Boston. Often hailed as America’s first modern hotel, guests entered a grand foyer and were shown to private, locking bedrooms – each equipped with a washbowl, pitcher, and a bar of soap, courtesy of the management. Even more incredibly, the Tremont House had indoor plumbing! It featured eight water closets (toilets)4 on the ground floor and running water supplied by a tank in the roof that was filled using a steam-powered pump. There were bathtubs in the basement which would be filled with cold water that was then heated by gas, and finally gas-lighting in every room.5

Soon similarly grand establishments were springing up all of over the country, though not all achieved the high standards set by Tremont House. Our old friend Dickens proved that he could be grumpy about his sleeping arrangement irrespective of which side of the Atlantic he was on, writing in American Notes (1842):

The most comfortable of all the hotels of which I had any experience in the United States, and they were not a few, is Barnum’s, in that city: where the English traveller will find curtains to his bed, for the first and probably the last time in America (this is a disinterested remark, for I never use them); and where he will be likely to have enough water for washing himself, which is not at all a common case.6

It wasn’t just the absence of curtains or the location of water that irked some European travellers. In most American hotels guests dined at communal tables regardless of social rank, and a traveler might rub elbows with merchants, lawyers, farmers, and senators in the same dining hall, all easting the same meal at the same time. This stood in sharp contrast to European customs, where class distinctions in lodgings persisted – the elites would generally stay in the houses of friends, or if forced to use a hotel then one that would be out of the financial and social reach of the hoi polloi. The English writer Frances Trollope, visiting America in 1832, was shocked by the informality she encountered:

The steam-boat had wearied me of social meals, and I should have been thankful to have eaten our dinner of hard venison and peach-sauce7 in a private room; but this, Miss Wright said was impossible; the lady of the house would consider the proposal as a personal affront, and, moreover, it would be assuredly refused. This latter argument carried weight with it, and when the great bell was sounded from an upper window of the house, we proceeded to the dining-room. The table was laid for fifty persons, and was already nearly full. Our party had the honour of sitting near “the lady,” but to check the proud feelings to which such distinction might give birth, my servant, William, sat very nearly opposite to me.8 The company consisted of all the shop-keepers (store-keepers as they are called throughout the United States) of the little town.

The expansion of railway networks in the mid-19th century vastly increased the number of people travelling both for business and for pleasure, and naturally these people needed someone to stay. The most obvious solution was to build a large hotel slap bang next to (or even above) the railway stations, and so ‘railway hotels’ were born. In Victorian Britain this led to the creation of some truly astonishing brick edifices, including my favourite, the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras Station in London, which opened in 1873:

The late 19th century also witnessed the birth of the ‘palace hotel’. These were not merely places to sleep; they were urban monuments designed to mirror the residences of the aristocracy. By attempting to replicate the opulence of royalty for a wealthy public, these hotels utilized soaring marble atria, gorgeous crystal lighting and vast corridors to cultivate a sense of awe. The goal was psychological: to make the paying guest feel like an esteemed visitor in a nobleman’s estate, and hence be happy to pay the steep price demanded to do so. The amenities kept pace too, by the 1870s, many grand hotels had gas lighting throughout (allowing for well-illuminated reading rooms and salons in the evenings) and indoor plumbing for bathrooms (often located down the hall, but increasingly en suite for deluxe rooms).

Perhaps nothing symbolized the technological leap of this age better than the adoption of the lift (elevator). In 1857, the first passenger elevator had been installed in a New York department store, and hotels soon followed. By the 1880s, luxury hotels were equipping themselves with ‘ascending rooms’. The five-storey Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York installed an early elevator (steam-powered) in the 1860s, and guests marvelled at being lifted to their floor without climbing stairs. In 1889, London’s Savoy Hotel one-upped its rivals by unveiling the first electric lifts in a British hotel. The Savoy was a showcase of late-Victorian innovation as it was also the first hotel in Britain fully lit by electricity, allowing guests to flip switches in their rooms to control the lights at will.9

Other palace hotels soon followed on the Continent and beyond. César Ritz, a visionary Swiss hotelier, managed and improved iconic properties like the Grand Hotel National in Lucerne and then the Savoy in London before founding his own Hôtel Ritz in Paris in 1898 (and London’s Carlton in 1899). Ritz became known for pioneering the credo that “the customer is never wrong”,10 instilling a new level of service excellence. His hotels were famed for lavish décor and innovative touches: private baths attached to suites, one of the first ‘concierge’11 staffs to arrange theatre tickets or travel for guests, and wonderful kitchens run by chefs like Auguste Escoffier.

In the 1850s another change began to work its way through the industry which would have doubtless pleased Frances Trollope. Rather than all guests eating the same meal, at the same time, often communally (hotel rates were usually full-board) the concept of having dining rooms with individual tables where one could choose one’s dishes from a menu became a thing.Hotels like Boston’s Parker House (opened 1855) offered this à la carte dining option to their guests and it soon became very popular.

Hotels spread wherever the European empires did. In colonial port cities and trading outposts, new hotels sprang up catering to Western travelers and expatriates. These establishments were often oases of European comfort in unfamiliar lands, and they took on an outsized romanticism in the Western imagination. Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo, founded in 1841 by Englishman Samuel Shepheard, became one of the world’s most celebrated hotels in the late 19th century – a gathering place for aristocrats, adventurers, and officers. It was said you could hear a dozen languages spoken on its terrace on any given evening. Shepheard’s was considered opulent for its day, yet Mark Twain,12 who stayed there in 1867, was decidedly unimpressed, writing in his notebook:

We are stopping at Shepheard’s Hotel – which is the worst on earth, except the one I stopped at once in a small town in the United States. It is pleasant to know I can stand Shepheard’s, because I have been in one just like it in America and survived.

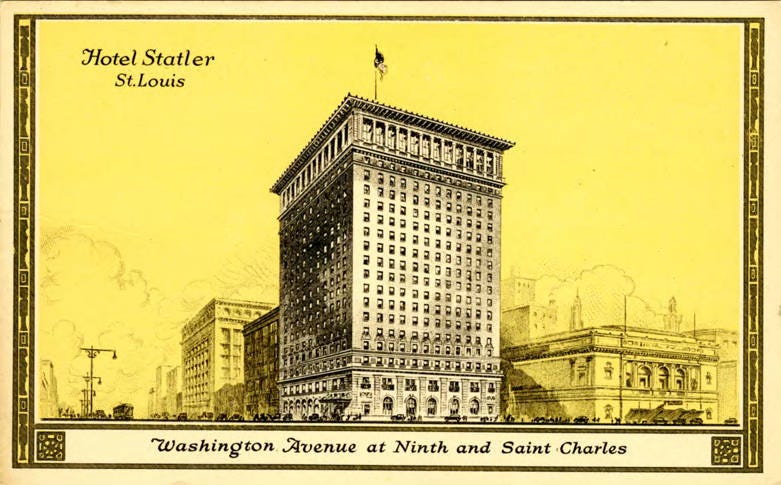

One feature of all of these hotels was that they were unique. I mean, of course, all hotels are unique, but nowadays a lot of them try to be incredibly similar to each other; they are parts of chains. Sure some companies in the 19th century owned multiple hotels but they never attempted to perfectly mimic each other. The godfather of the chain hotel was one Ellsworth Milton (‘E. M.’) Statler (1863–1928) who started off by building vast, temporary hotels, at expos – such as the 2,100 room monster he constructed for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Using the money that he made from this he decided to build permanent hotels that would be of decent quality and, critically, have a private bathroom for every room. To achieve this he created the Statler plumbing shaft – something which is so common today, and so seemingly obvious, it may be surprising that someone had to come up with the idea in the first place.

The idea was simple, yet novel – build hotels with a common vertical service shaft running basement-to-roof, where two adjacent guest rooms had bathrooms placed back-to-back, stacked identically floor-to-floor, so they could share one concentrated run of water/waste lines (and often other utilities) – cutting the building cost and simplifying ongoing maintenance. Statler probably came up with the concept when building his vast, temporary, hotels where budgets were stripped to the bone and efficiencies had to be found wherever possible. He opened his first hotel in Buffalo in 1907 and charged a mere $1.5013 a night, and used the advertising slogan “A Room and a Bath for a Dollar and a Half”. Statler’s innovations did not, however, end with the plumbing. He standardised not just the designs of the rooms and the hotels but the level of service guests could expect. Every member of staff had to sign off on the following eight-point pledge:

To treat our patrons and fellow employees in an interested, helpful, and gracious manner as we would want to be treated if positions were reversed;

To judge fairly–to know both sides before taking action;

To learn and practice self-control;

To keep our properties—buildings and equipment—in excellent condition at all times;

To know our job and to become skillful in its performance;

To acquire the habit of advance planning;

To do our duties promptly; and

To satisfy all patrons or to take them to our superior.

The rational behind this pledge was obvious to Statler,14 who wrote:

Statler Hotels are operated primarily for the comfort and convenience of their guests. Without guests there could be no Statler Hotels. These are simple facts, easily understood. It behooves every man and woman employed here to remember this always, and the treat all guests with courtesy and careful consideration.

By 1955, when the chain was purchased by Hilton for $111m15 it consisted of 10,400 very similar, but very affordable, hotel rooms that provided their guests with consistent, great, service. In the absence of Statler I am pretty sure that someone would have come up with, and implemented, similar ideas at scale, but I can’t help but think that without him the development of hotels as we know them would have been set back years, if not decades. The Hilton chain that bought Statler out, for instance, didn’t open their first hotel until 1919, some 12 years after E. M. first opened his. As it happens I am finishing this piece on the morning of December 3116 before travelling up to Glasgow for Hogmanay. I am sure that when I check into my hotel17 this evening I will give a little nod of thanks to E. M. knowing now, as I do, that without him hotels could have been rather different today.

Well the building survives at least. In addition to Dickens, the inn has hosted King George the Second, Admiral Nelson and the Beatles!

For a long time it was thought that this was the first establishment in England calling itself a hotel, but in fact the German Hotel in London had been doing so since at least 1710.

At the time an unskilled labourer would perhaps $10-14 a month for a 60-hour work week, so this cost would be of the order of several thousand dollars a week in today’s terms. That said, one can easily spend that much on seven nights in a decent hotel room in New York in 2026, and that 19th century price would also have included all meals.

Yup, up until that point guests would have had to use outhouses, or chamber pots in their rooms. It is worth noting though that Tremont House had 170 rooms, so eight loos doesn’t really feel like enough, but I guess that it was a step in the right direction.

Way better than what had gone before, but not great by today’s standards, see Footnote 9.

While European inns would generally provide basins and pitchers of water in each of the rooms, many American hotels, initially at least, would expect their guests to use a common basin or washroom.

I can’t say that this sounds the most appetising…

Imagine being seated close to one’s servant at dinner! The horror!

This may not seem like a big deal to us today, but the previously used gas lamps were a nightmare. Leaving aside the hassles of lighting and maintaining them, they would throw out a lot of heat, soot, and water vapour. Oh, and could accidentally kill you through carbon monoxide poisoning if not properly maintained.

Him saying “Le client n’a jamais tort” was first recorded in a book of 1908. He was, however, quite possibily drawing upon earlier uses of the same, or a similar, phrase.

Concierge meaning ‘keeper of the keys’.

I am not sure if writers are an unusually grumpy bunch when it came to hotels, or it is more that we know that they were grumpy because their writings survive.

That year a bricklayer in Buffalo earned around $0.55 an hour, so the cost of a room for the night was less than three hours of gross wages.

It is said, and this might be apocryphal, that he would go around his newly constructed hotels timing how long it took for the baths to fill and the toilets to flush!

Somewhere between $1.3bn and $2.0bn today.

Which is also, weirdly, my birthday. Well I guess no weirder than any other day, but when I tell people the date they often say “What, New Year’s Eve? Really?”.

[Later update] The Dakota, it was lovely, the staff were excellent, E.M would have been proud!

Happy belated birthday. Dakota hotels in the UK are nice, tend to be dark, yet modern.

As a freelancer doomed to spend dozens of nights a year in hotels, I’ve really enjoyed this comprehensive history. I shall never take my cramped, rather shabby en suite for granted again!