A history of… hotels (Part 2)

According to Erasmus, French inns were much more welcoming than German ones...

In my previous piece I explored how lodges developed over a period of around three thousand years. Some were official government accommodations, some were operated by religious institutions, and some, though somewhat fewer, were run as private enterprises. With the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire in Europe in the fifth century official networks of inns declined1 (though they survived and thrived in other parts of the world). At the same time there was a material decline in trade, and hence fewer people going from place to place. This didn’t, however, stop people needing to travel entirely, and some still needed to find a place to stay when away from home. While some private inns doubtless continued to function many people found refuge in an increasing network of Christian religious institutions.

That such accommodations could be found was due in no small part to the work of Saint Benedict (480-547) whose ‘Rule for Monasteries’ (written in about 530) took great pains to ensure that these places could be sanctuaries in the increasingly lawless Italy of the sixth century. Rule 53 took particular inspiration from Matthew 25:35: “For I hungered, and ye gave Me meat; I was thirsty, and ye gave Me drink; I was a stranger, and ye took Me in” and explains in detail how visitors should be treated:

Let all guests who arrive be received like Christ, for He is going to say, “I came as a guest, and you received Me.” And to all let due honour be shown, especially to the domestics of the faith and to pilgrims.

As soon as a guest is announced, therefore, let the Superior or the brethren meet him with all charitable service. And first of all let them pray together, and then exchange the kiss of peace. For the kiss of peace should not be offered until after the prayers have been said, on account of the devil’s deceptions.

In the salutation of all guests, whether arriving or departing, let all humility be shown. Let the head be bowed or the whole body prostrated on the ground in adoration of Christ, who indeed is received in their persons.

After the guests have been received and taken to prayer, let the Superior or someone appointed by him sit with them. Let the divine law be read before the guest for his edification, and then let all kindness be shown him. The Superior shall break his fast for the sake of a guest, unless it happens to be a principal fast day which may not be violated. The brethren, however, shall observe the customary fasts. Let the Abbot give the guests water for their hands; and let both Abbot and community wash the feet of all guests. After the washing of the feet let them say this verse: “We have received Your mercy, O God, in the midst of Your temple.”

In the reception of the poor and of pilgrims the greatest care and solicitude should be shown, because it is especially in them that Christ is received; for as far as the rich are concerned, the very fear which they inspire wins respect for them.

Saint Benedict also understood of having a competent person on the medieval equivalent of the hotel reception desk:

At the gate of the monastery let there be placed a wise old man, who knows how to receive and to give a message, and whose maturity will prevent him from straying about.2 This porter should have a room near the gate, so that those who come may always find someone at hand to attend to their business. And as soon as anyone knocks or a poor man hails him, let him answer “Thanks be to God” or “A blessing!” Then let him attend to them promptly, with all the meekness inspired by the fear of God and with the warmth of charity.

Some of us have doubtless encountered guests who have overstayed their welcome and this was a concern in medieval times as well – monasteries didn’t have unlimited resources and feeding and housing visitors placed demands upon their supplies. There soon developed an informal ‘three-day rule’: you could stay for that long and be given everything that you needed, but then you really had to be on your way. Among the Franciscans, for example:

The usual period was apparently two days and nights, and in ordinary cases after dinner on the third day the guest was expected to take his departure. If for any reason a visitor desired to prolong his stay, permission had to be obtained from the superior by the guest-master. Unless prevented by sickness, after that time the guest had to rise for Matins, and otherwise follow the exercises of the community. With the Franciscans, a visitor who asked for hospitality from the convent beyond three days, had to beg pardon in the conventual chapter before he departed for his excessive demand upon the hospitality of the house.

Where no religious institution existed, it was customary for people to seek accommodation in houses of strangers, but again three days was generally considered to be the limit on how long you could stay there for free. After that point the person would then be considered to be part of the household, and the host would have legal responsibility for them, a strong inventive for getting them out the door! This was even codified in the Kentish Laws of Hlothere and Eadri (c.673-c.686):

If anyone provides for a stranger in his own home for three nights – a merchant or another who has come across the border – and he feeds him his food, and he [the guest] then does harm to any person, the man [the host] should bring the other to justice otherwise make forfeiture.

The same laws also called for strict punishments if you were rude in someone else’s house:

If anyone in another’s dwelling calls a person a perjurer or addresses him with shameful insults, he must pay a shilling to him who owns that dwelling, and 6 shillings to the one to whom he spoke that utterance, and he should pay to the king 12 shillings.3

As Europe moved into the second millennium there was a resurgence of trade which created a demand for lodgings that religious institutions and private homes alone were unable to meet. To accommodate them we see commercial inns being set up, such as the one in Bergen, Norway established by King Eystein Magnusson (reigned 1103-1123), while in Venice a century later we have what could be considered a proto-hotel. The Fontego dei Tedeschi was established in the 1220s as a trading hub, warehouse and accommodation for German merchant visitors to the city. Over time it expanded to house over 100 travellers and while not a hotel per se (it was limited to a specific class of guest) it was certainly a form of commercial mass accommodation for visitors.

Meanwhile a network of somewhat more modest, but no less significant, coaching inns sprang up across the continent. The Tabard Inn was founded in Southwark in 1307 on what is now Borough High Street where it was crossed by the ancient road to Canterbury and Dover (and hence on a major pilgrimage route). It is particularly notable because this is where Chaucer’s pilgrims gathered before setting off on their journey as recorded in The Canterbury Tales (1387-1400):

Bifel that in that season on a day,

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay

Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,

At nyght was come into that hostelrye

Wel nyne and twenty in a compaignye

Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle

In felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle,

That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde;

The chambres and the stables weren wyde,

And well we weren esed atte beste;

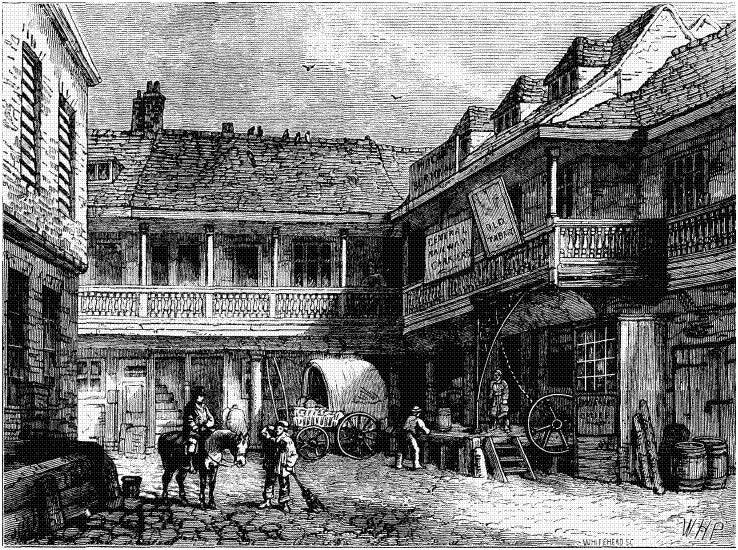

Sadly the inn was demolished in 1873;4 however, on the site next door you can find one of my favourite London pubs, the George Inn.5 It is of similar medieval foundation, with the current building dating from 1677 (Dickens used to drink there and it is mentioned in Little Dorrit). In my home town of Oxford there is the even older Golden Cross which was first established as an inn in 11936 by a vintner named Mauger. The current buildings date from the late 15th century and the courtyard is probably where Shakespeare’s King’s Men performed in 1610.7

The quality of one’s inn experience varied from country to country as the writer Erasmus (Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus, 1466-1536) describes in his Colloquia familiaria (1518-1533). Firstly the experience in France:

There’s a Woman always waiting at Table, which makes the Entertainment pleasant with Railleries, and pleasant Jests. And the Women are very handsome there. First the Mistress of the House came and bad us Welcome, and to accept kindly what Fare we should have; after her, comes her Daughter, a very fine Woman, of so handsome a Carriage, and so pleasant in Discourse, that she would make even Cato himself merry, were he there: And they don’t talk to you as if you were perfect Strangers, but as those they have been a long Time acquainted with, and familiar Friends.

And because they can’t be always with you, by Reason of the other Affairs of the House, and the welcoming of other Guests, there comes a Lass, that supplies the Place of the Daughter, till she is at Leisure to return again. This Lass is so well instructed in the Knack of Repartees, that she has a Word ready for every Body, and no Conceit comes amiss to her. The Mother, you must know, was somewhat in Years.

But what was your Table furnish’d with? For Stories fill no Bellies.

Truly, so splendid, that I was amaz’d that they could afford to entertain their Guests so, for so small a Price. And then after Dinner, they entertain a Man with such facetious Discourse, that one cannot be tired; that I seemed to be at my own House, and not in a strange Place.

This is sharp contrast to what happens in Germany:

I can’t tell whether the Method of entertaining be the same every where; but I’ll tell you what I saw there. No Body bids a Guest welcome, lest he should seem to court his Guests to come to him, for that they look upon to be sordid and mean, and not becoming the German Gravity. When you have called a good While at the Gate, at Length one puts his Head out of the Stove8 Window (for they commonly live in Stoves till Midsummer) like a Tortoise from under his Shell: Him you must ask if you can have any Lodging there; if he does not say no, you may take it for granted, that there is Room for you. When you ask where the Stable is, he points to it; there you may curry your Horse as you please yourself, for there is no Servant will put a Hand to it.

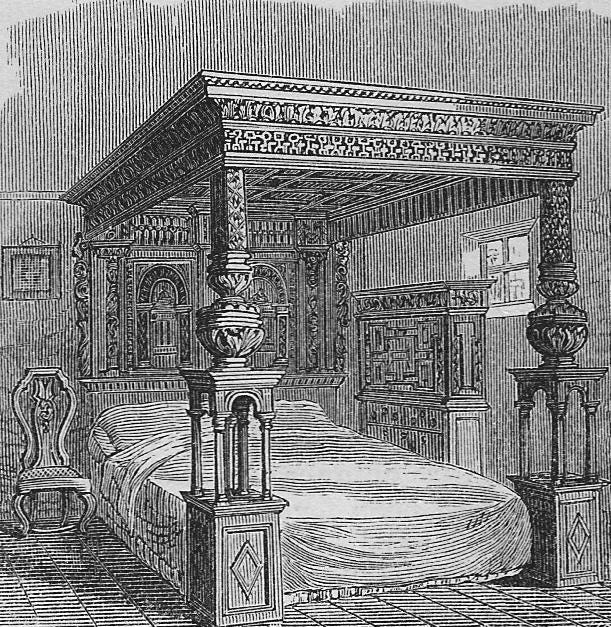

You might be wondering if the female staff/patrons at inns of this time provided more than witty repartee to customers and the answer to this was often ‘yes’. Inns of this era were bawdy places: in addition to the obvious alcohol there were gambling, prostitution and other vices on offer. I’ll end this week by talking about a strange piece of stunt marketing9 for an inn which made a knowing wink at this reputation for licentiousness. In around 1590 the White Hart Inn in Ware, Hertfordshire commissioned a carpenter named Jonas Bosbrooke to build a massive bed – 3.38 metres long by 3.26m wide (about 11 feet by 10). Advertised as being able to accommodate four couples what soon became known as ‘The Great Bed of Ware’ drew people to both gawp at it and spend the night in it. Prince Ludwig of Anholt-Kohten stayed there in July 1596 and wrote:

At Ware was a bed of dimensions so wide,

Four couples might cosily lie side by side,

and thus without touching each other abide

While it might have been possible for multiple couples to spend the night in the bed “without touching” its notoriety was based more upon the bawdy opportunities that it offered. One legend claimed that, in 1689, 26 butchers and their wives spent the night frolicking in it!10

Now you might be doubting quite how famous a big bed might be. I mean, for sure, it was a really big bed but is that something people are really going to talk about? Let me put it this way: in 1601, just 11 years after it had been made, Shakespeare considered it famous enough to mention in Twelfth Night11 where Sir Toby Belch tells Sir Andrew to write a furious challenge:

…as many lies as will lie in thy sheet of paper, although the sheet were big enough for the bed of Ware in England

Eight years later Ben Jonson mentions it in his play Epicoene and centuries later Byron references it in Don Juan!

In my next piece12 I’ll bring the story of hotels finally up to the modern day with the development of chains, luxury hotels and the like.

It feels as though every other piece that I write has something along the lines of “things got worse in Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire” and doubtless for good reason.

I particularly appreciate this point, having arrived late at night to hotel reception desks only to find no one there and then listlessly hanging around for a while, waiting for someone to appear, when all I want to do is get into bed.

It is not clear, what, if any, punishment was incurred if you were rude in your own house.

I find this fact to be a devastating shame. Imagine being able to drink in the same pub as Chaucer!

If you are thinking of going there be warned that it is usually absolutely rammed with City of London workers until around eight in the evening on weekdays. Your best bet is normally the room immediately on the right as you come into the courtyard, which is separate from the main bar.

I love the fact that people have been drinking beer on this site for more than 800 years (albeit today only in Pizza Express), but I’ll endeavour to stop myself turning this piece into ‘Paul’s favourite pubs’.

Possibly Hamlet.

‘Stove’ in this context means a heated living room, related to the German Stube. It was only later in English that stove came to mean a fuel burning metal box for cooking and heating. The point being made here seems to be that the place was so cold it wasn’t until midsummer that the climate improved sufficiently for the locals to inhabit other rooms.

I kind of love the fact that PR stunts have a history going back more than 400 years.

Give that the area of the bed was 110 square feet, and there were 52 people in total, the roughly two square feet per person suggests that this story might at best be somewhat hyperbolic.

Demonstrating not only, obviously, that Shakespeare had heard of it, but also that he knew that it was so famous he could safely reference it and people would know what he was talking about.

Yes, I had intended this to be a two-parter, but I got somewhat carried away.

Love the through-line from Benedictine hospitality protocls to modern hotel service. The three-day rule makes me think of how Silicon Valley startups still wrestle with similar boundries around free perks and workspace access. Also interesting how courtyards went from defensive architecture in monasteries to the defining feature of coaching inns once saftey allowed it.

Love this series, Paul! Although you apologize for going beyond two articles, I wouldn’t mind reading more about the situation outside Europe.