At around one o’clock in the afternoon of Saturday, 14th July 1736 a bomb exploded in the Court of Chancery in the Houses of Parliament. Chaos ensued as the great and the good fled the scene, coats billowing and wigs flying as they rushed to make their escape. The intent of the bomber, one Robert Nixon, was not to cause death and destruction, or even to cause panic, but rather to send a message. The bomb itself was not particularly powerful, but it was wrapped with printed bills that were spread far and wide by the force of the explosion. The bills read:

By a general consent of the citizens and tradesmen of London, Westminster and the borough of Southwark, this being the last day of term, were publickly burnt, between the hours of twelve and two, at the Royal Exchange, Cornhill, at Westminster Hall… and at Margaret’s Hill, Southwark, as destructive of the product, trade and manufacture of this kingdom and the plantations thereto belonging, and tending to the utter subversion of the liberties and properties thereof, the five following printed books, or libels, called Acts of Parliament.

At the top of the list of these Acts of Parliament to be burned was the 1736 Gin Act. As we learned in Part One of this history, the intent of this act was to curtail the ruinous gin consumption that was bedevilling London, but all it succeeded in doing was to push the trade underground, and, err, lead to the invention of gin-dispensing cats…

A powerful anti-gin lobby emerged, which included Thomas Wilson, the Bishop of Sodor and Man, who presented a 60-page report to Parliament on the evils of the spirit, noting that gin had created a “drunken ungovernable set of people”:

’Tis a certain and known Maxim, that the Strength and Riches of any Nation arise principally from the Number, bodily Strength, and Labour of its Inhabitants; and consequently, in proportion as these are diminished, so must the Riches and Power of a Nation decrease. That this is the Effect of the excessive drinking Spirituous Liquors, will appear evidently…

Realising that the Gin Act was actually creating more harm than good and had done nothing to reduce the amount being drunk, Parliament repealed it in 1743. The return to legitimacy did something to improve the quality of the products being sold, but it didn’t slow the gin craze.

A leading light of the anti-gin movement was the novelist Henry Fielding (the author of Tom Jones) who in 1751 published ‘An Enquiry Into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers’1 in which he laid out in no uncertain terms the case that gin was the cause of vice and depravity in society:

That in there Beds, several of which are in the same Room, Men and Women, often Strangers to each other, lie promiscuously, the Price of a double Bed being no more than Threepence, as an Encouragement to them to lie together: That as these Places as thus adapted to Whoredom, so they are no less provided for Drunkenness, Gin being sold in them at a Penny a Quartern; so that the smallest Sum or Money serves for Intoxication.

Fielding did more than simply detail problems, he went on to suggest solutions:

Suppose all spiritous Liquors were, together with other Poison, to be locked up in the Chemists or Apothecaries Shops, thence never to be drawn, till some excellent Physician calls them forth for the Cure of nervous Distempers! Or suppose the Price was to be raised so high, by severe Import, that Gin would be placed entirely beyond the Reach of the Vulgar!2

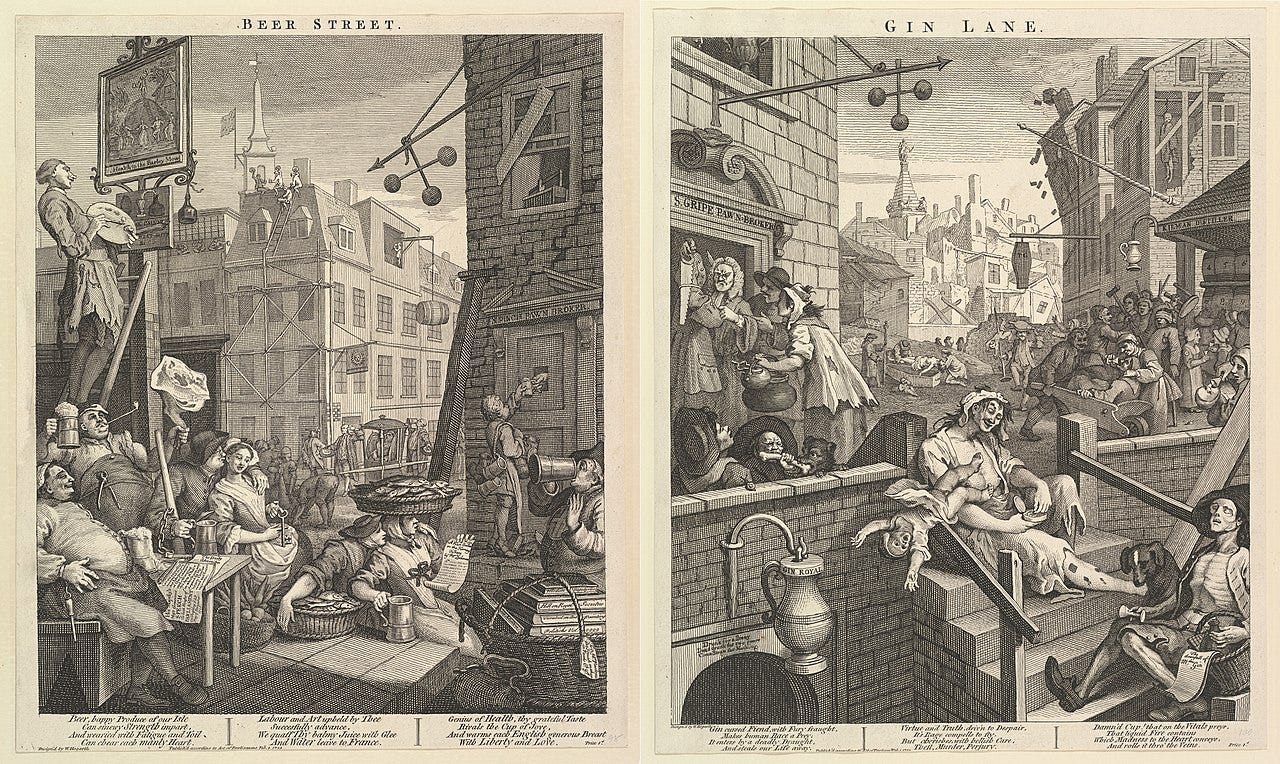

Fielding’s friend, the artist William Hogarth created the most famous image associated with the gin craze in the same year – ‘Gin Lane’.

In it we see a half-naked woman, syphilitic sores on her legs, addled by gin, letting her baby tumble to its death. Children compete with dogs for bones, possessions are pawned to buy more of the demon drink, and in the background one poor soul has hung himself out of desperation. Underneath the image is a verse written by the dramatist and priest James Townley:

Gin, cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught,

Makes human Race a Prey.

It enters by a deadly Draught

And steals our Life away.

Virtue and Truth, driv’n to Despair

Its Rage compells to fly,

But cherishes with hellish Care

Theft, Murder, Perjury.

Damned Cup! that on the Vitals preys

That liquid Fire contains,

Which Madness to the heart conveys,

And rolls it thro’ the Veins.

It is worth mentioning that Hogarth was not totally opposed to alcohol, rather spirits in general and gin in particular, due to their deleterious effect on the poor. The companion piece to ‘Gin Lane’ was an illustration called ‘Beer Street’. In it cheerful, productive, people can be seen happily quaffing away on beer. Townley wrote a verse that was included beneath this illustration as well, and it strikes a much more positive tone:

Beer, happy Produce of our Isle

Can sinewy Strength impart,

And wearied with Fatigue and Toil

Can cheer each manly Heart.

Labour and Art upheld by Thee

Successfully advance,

We quaff Thy balmy Juice with Glee

And Water leave to France.

Genius of Health, thy grateful Taste

Rivals the Cup of Jove,

And warms each English generous Breast

With Liberty and Love!

Things began to change shortly after the introduction of the Sale of Spirits Act 1750 (also known as the Gin Act 1751). Somewhat less draconian than the 1736 law, it limited the sale of gin to licensed establishments in a bid to reduce illegal sales, along with promoting the consumption of tea and beer. There was a significant reduction in the levels of gin consumption in the years that followed, but most historians agree that this had nothing to do with the act. Food shortages, caused by poor harvests and an increasing population, pushed up the price of grain, thus increasing the cost of gin considerably.

Moving into the 19th century, gin became a much more sophisticated drink. So much so that rather than being drunk on the street or in back-street dives, elaborate buildings, gin palaces, were constructed for its consumption. These were hugely ornate buildings, lit by gas lamps and full of mirrors where one could sip and sup in style. In his Sketches by Boz, Charles Dickens wrote of them as being “perfectly dazzling when contrasted with the darkness and dirt we have just left…”.

Gin at this time was mostly served mixed with water and bitters, or sometimes with fruit juices or vermouths, but it wasn’t too long before tonic entered the picture.

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by a single-celled parasite which is spread by mosquitoes. It is hard to assess its total impact upon humanity; however, many experts agree that it has been responsible for around 5 billion3 human deaths over the course of history. For most of that time the only effective treatment for malaria was the chemical quinine. The Quechua people of South America had been using it for millennia in the form of bark from the cinchona tree, before Jesuit missionaries transported it to Europe to treat malaria in the late 16th century.

By the early 19th century, quinine had been isolated from the tree bark and was being given to soldiers in British India as a prophylaxis against the disease. To make its bitter taste somewhat more palatable they mixed it with sugar and soda water, thus creating an early form of tonic water. It was soon realised that this drink could be made even nicer by mixing it with their daily gin ration (of course soldiers had a daily gin ration, after all, sailors had their rum – I have found references to it being half a pint, or more than 10 shots, a day!). Or at least that is the commonly told story. It seems more likely that the soldiers of the time were mixing their quinine with whatever booze they had available, including port and sherry. And whatever they were drinking it was a far cry from the drink we know today, as it would have had around ten times the amount of quinine in it that modern tonic water has and as a result would have been incredibly bitter.

The first commercial tonic water was patented by Erasmus Bond, the owner of Pitt & Co. in 1858, but in its early years it was sold for its medicinal properties, as this article from The Lancet in 1862 shows:

It wasn’t long before drinking a combination of gin and tonic became something one did for pleasure, rather than just health, as suggested by this reference in the Oriental Sporting Journal describing a horse race in Sealkote (now called Sialkot, a city in Pakistan) from 1868 (the earliest known mention of gin and tonic in print).

Aided by the reach of the British Empire, the gin and tonic soon became a global drink, one that can be found in almost every bar in the world, albeit with some regional variations. In Spain the gin tonica is normally served in a balloon wine glass, with a large amount of ice and additional aromatic garnishes, for example. In Uganda you will find waragi, also known as ‘war gin’ in a nod to its origins as a stiffener for the British troops stationed there. It is fairly harsh spirit, often distilled from fermented bananas, and sold in plastic bags as well as bottles. Having sampled it in Kampala I have to say that if it is an acquired taste, it is not one that I have a great urge to acquire…

The most popular gin brand in the world is one that you have likely never heard of, Ginebra San Miguel. This Philippine gin services the huge demand of its local market and outsells the second most popular brand, Gordon’s, by 5:1, shifting around half a billion bottles each year. I have drunk it in Manila and it is pretty decent, certainly better than waragi!

To close, I’d like to leave you with what Sir Winston Churchill had to say about this glorious drink:

Gin & Tonic has saved more Englishmen’s lives, and minds, than all the doctors in the Empire.

If you ever bump into me, and I have a G&T in my hand, you can rest assured that I am drinking it purely for medicinal purposes.

Or to give it its full title ‘An Enquiry Into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers, &c. with Some Proposals for Remedying this Growing Evil In which the Present Reigning Vices are Impartially Exposed; and the Laws that Relate to the Provision for the Poor, and to the Punishment of Felons are Largely and Freely Examined’. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

Capitalisation is as per the original text. I come across this a lot in 18th-century texts and have no idea what the rhyme nor reason for it is.

Estimates are as high as 50 billion but most people think that this is unrealistic.

Wonderful! While we do call tonic water "agua tonica" the drink is, at least since 2015-ish called "gin tonic". Many bars will serve over ten kids of gin tonic and each is adorned with different garnishes.