A history of… firefighting (Part 2)

Why not try exploding some barrels of water?

In my previous post I wrote about the history of organised firefighting. What I didn’t do was talk about what people in the past used to actually fight fires, so I am going to delve into that now. Probably the most obvious way to extinguish a fire is to chuck one or more buckets of water over it and indeed this technique has been employed over a large swath of human history. The problem with using buckets, however, is that there is a limited distance that you can sling the water and the history of attempts to resolve this issue is surprisingly long.

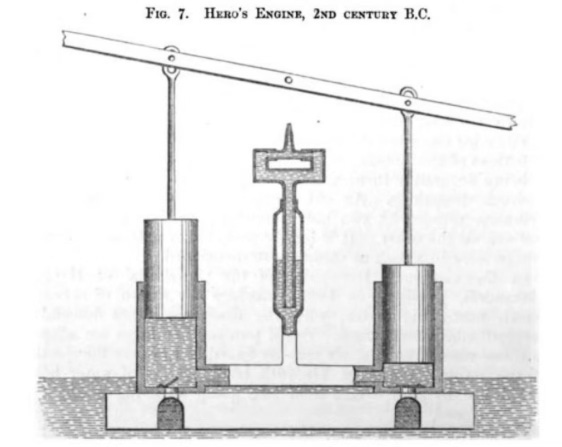

Back in the third century BCE, Ctesibius of Alexandria invented the first fire pump and this was improved on by Heron of Alexandria (also known as ‘Hero’, more famous for the invention of the first known steam engine). As Charles Young records in his 1866 book Fires, Fire Engines, and Fire Brigades:1

The fire engine or pump used in extinguishing fires, and by means of which a stream of water could be thrown amongst the flames through the power of several men, is of very ancient origin, for we find that its invention is attributed, and on sufficient evidence, to an engineer of Alexandria, Ctesibius by name, who flourished in the second century2 before the birth of Christ, during the time of Ptolemy Philadeiphus and Euergetes.

Of Hero it may be said that he produced a practical engine, on which the moderns have scarcely improved: he used metallic pistons; spindle valves with guards to prevent their opening too far; the formation of the gooseneck by a sort of swivel joint something like a union or coupling screw; the application of an air vessel; two pumps forcing the water through one pipe, and one lever to work both pumps…Hero describes a moveable tube fitted by a joint [gooseneck] to the perpendicular one, by turning of which the stream of water can be thrown in any direction, and refers to the sketch to prove it. A small air vessel is shown with the bottom of the discharge pipe under the water, and he expressly states that the water was forced out by means of compressed air.

This was not the only means of firefighting available to the Greeks, as Young continues:

It seems that besides engines for throwing water on fires, they used sponges or mops attached to the ends of long poles, and grapples and other instruments by means of which they could go from one wall to another.

As with much technology, there wasn’t a great deal of improvement made over the next 1,500 years. In 1650 the German engineer Hans Hautsh (1595–1670) invented a compressed air-powered fire engine which could shoot water to a height of 20 metres (65 feet). This was achieved by having two teams of 14 men working a piston back and forth to build up the pressure.

As you can see from the picture, this was a pretty large piece of kit, which had to be dragged on a sled to the location of the fire. The English inventor Richard Newsham improved the concept in the early 18th century creating a wheeled device that we would probably recognise today as a fire engine. It held 640 litres (170 US gallons) of water and a team of men could pump out up to 380 litres (100 US gallons) of water a minute. So successful were they that the city of New York imported two of the engines in 1731.

On of the challenges of using these engines was that they had to be continually supplied with water. This was achieved using ‘bucket brigades’ – lines of men between the engine and the nearest water supply who would pass brimming buckets from hand to hand. This problem was solved in 1822 by the Philadelphia-based company Sellers and Pennock who invented the Hydraulion – an engine with a suction hose that slurped water up directly into its cistern. In this illustration from 1838 you can see the supply hose snaking off to the right:

These were still large, heavy contraptions and while they could be moved into place by horses (or men), response times were slow. The first attempt to improve things by introducing a steam-driven engine in New York in 1841 didn’t work out too well, however. The device was sabotaged by a group of firemen (presumably fearing that it would reduce the need for their labour) and was discontinued. Steam did take hold in the second half of the 19th century, before being supplanted by petrol-driven engines, the first of which was introduced in Paris in 1897.

What though about that other tool for firefighting, the fire extinguisher? This too has a surprisingly long history. I think that it is fair to say that the first fire extinguisher, patented in 1723 by the chemist Ambrose Godfrey, was somewhat different to the ones we use today. This is how Ambrose describes it:

The new method I have to offer to the publick consists of gunpowder closely confined, which as soon as animated by fire acts by its elastic force upon a proper medium [water impregnated with a certain preparation] and divideth it instantly into millions of millions of most minute and imperceptible atoms, which with equal violence and swiftness arc immediately forced into the innermost recesses of the flames… The constituent parts of the machines are the shell and the powder magazine. The shell is a small wooden barrel with wooden hoops: in the middle of the top an opening is left for the fuzee to pass through. This band is cased without and well lined within, the better to hold the liquid: which is a mixture which never corrupts or alters, when on the contrary mere water would soon putrify and stink.

Yes, this is basically a barrel full of water, in the middle of which is a metal chamber of gunpowder with a fuse coming out of it. Light the fuse, the gunpowder explodes, blasting apart the barrel, thus dispersing the water. On 30th May 1723 Ambrose carried out a demonstration of his brilliant new invention for the Society of Arts on Marylebone fields – a purpose-built house was set on fire and extinguished by the exploding barrels! They may seem crazy, but it seems that they really did work, as this account from Bradley's Weekly Messenger of November 7, 1727 shows:

Last Sunday… a fire broke out at the Crown Tavern, in King-street, near Guildhall. The same morning, I am informed, two other fires occurred, but I have not heard the particulars. In some of these, however, I hear that the famous machines, or fire watches, invented by Mr. Godfrey, the great chymist, in Southampton-street, Covent-garden, display’d their wonderful effects, and prevented the progress of that furious element; with what quiet and satisfaction may we not therefore live when we have the advantage of such safeguards.

A more modern fire extinguisher was invented by British Army captain George William Manby in 1813. Manby is probably deserving a post all to himself, as he also invented the Manby mortar, a device for firing rescue lines to stricken ships which saved more than 1,000 people during his lifetime. His extinguisher, the Extincteur, was a copper cylinder which used compressed air to squirt three gallons of potassium chloride solution onto the fire. In 1866 the Frenchman Francois Carlier patented an extinguisher that used a combination of sodium bicarbonate and acid to create carbon dioxide to propel the water out, but it wasn’t until 1924 that the Walter Kiddle Company introduced a model that used solely CO2 to extinguish fires.

A fairly short-lived alternative to the extinguisher was the fire grenade. This was a glass flask containing carbon tetrachloride (CTC) which was thrown at the base of the fire where, upon shattering, the chemical would inhibit the chain reaction of combustion and suppress the fire. These devices worked surprisingly well, until it was realised that CTC was viciously toxic and, worse, when heated could produce phosgene gas (best known for its use as a chemical weapon in World War One).

Not all fires take place in urban areas. Wildfires can occur in places hundreds of miles from the nearest track or road. How then do you fight a fire that could take days or weeks to reach on foot? The solution, developed in the 1940s, was Smokejumpers. These are men parachuted into the area of a wildfire tasked with cutting firebreaks to curb the progression of the blaze. Equipped with axes, entrenching tools and sometimes even dynamite (for blasting), along with 48 hours of food and water, their work was often exceptionally dangerous. If you would like to learn more about them I strongly recommend Young Men and Fire, by Norman Maclean, which explores the Mann Gulch Fire tragedy of 1949. Part technical investigation, part tribute, part mediation on mortality, it is probably the best non-fiction book I have ever read. I will leave you now with some of his words:

It was 1940 when the first parachute jump on a forest fire was made, and a year later that the Smokejumpers were organised, so only for nine years had there been a profession with the aim of taking on at the same time three of the four elements of the universe – air, earth, and fire – and in the simple continuous act dropping out of the sky and landing in a treetop or on the face of a cliff in order to make good their boast of digging a trench around every fire they landed on by ten o’clock the next morning. In 1949 the Smokerjumpers were still so young that they affectionately referred to all fires they jumped on as “ten o’clock fires”, as if they had them under control before they jumped. They were still so young that they hadn’t learned to count the odds and to sense they might owe the universe a tragedy.

Or to give it its full title, Fires, Fire Engines, and Fire Brigades: A History of Manual and Steam Fire Engines, Their Construction, Use, and Management; Remarks on they Fire-Proof Buildings, and the Preservation of Life from Fire; Statistics of the Fire Appliances in English Towns; Foreign Fire Systems; Hints for the Formation, and Rules for, Fire Brigades; and an Account of American Steam Fire Engines. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

It seems that Young was mistaken about this date.