A history of… duels (part 2)

You can get shot in the head twice and still enjoy 'good health'…

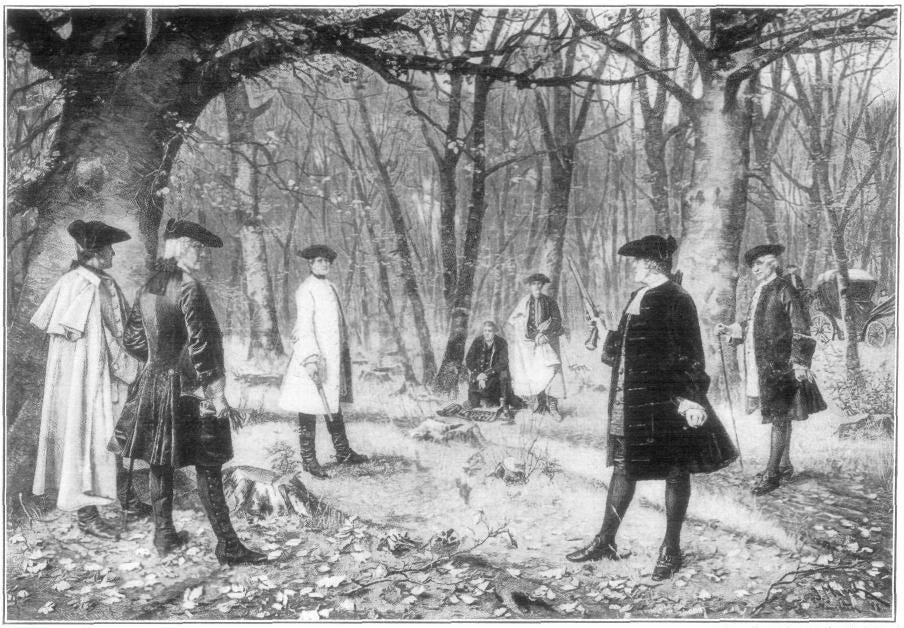

In my previous piece I explored the origins of duels, and their role as part of the formal legal system. This week I’ll be looking at how they developed, particularly with the invention of firearms, but before I do so I thought that it would be interesting to look in a little bit more detail about the processes involved in a formal duel.

If some types of historical drama are to be believed, then the stages of a duel are as follows:

One man insults another’s honesty/wife/mother/pet cat.

The offended party pulls off one his gloves and slaps the other across the face with it.

The following morning they meet at a secluded spot to settle the matter with swords or guns.

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that there is actually a fair bit more to it than that. After an insult had been given, what would generally happen is that the recipient of the abuse would write a formal challenge, called a cartel, which his second would take to the aggressor. The cartel should follow a standard form, as The Art of Duelling (see later) describes:

The most accredited mode is to conduct the whole affair with the greatest possible politeness, expressing the challenge clearly, avoiding all strong language, simply stating, first the cause of the offence; secondly, why it is considered a duty to notice the matter, thirdly, naming a friend; and lastly, requesting the appointment of a time and a place.

If abroad it is proper to state at the foot of the letter the length of the challenger’s sword-blade; and a correct copy should be kept of all correspondence that takes place.

It is important to realise that unless someone was an excellent duelist (and/or was a psychopath – we’ll encounter one of those later on) people generally didn’t want to fight duels. In the days before antibiotics and modern medicine even if you were victorious it was easy to become disfigured or acquire a fatal infection in the process. The role of the second was very important here: in delivering the cartel they would aim to be very diplomatic and try and defuse the situation. The wording of the cartel was similarly significant; ideally it should be written in a manner to allow the instigator to back out of the situation honourably (or as honourably as possible).

Sometimes though, the cartel sender was spoiling for a fight, such as this man, furious at his cross-examination by a barrister:

Sir: You are renowned for great activity with your tongue, and justly, as circumstances that have occurred today render evident. I am celebrated for my activity with another weapon, equally annoying and destructive; and if you would oblige me by appointing a time and a place, it would afford me the greatest pleasure to give you a specimen of my proficiency.

Yours obediently

Many jurisdictions ratified formal rule sets for duelling, such as the code duello “adopted at the Clonmel Summer Assizes, 1777, for the government of duellists, by the gentlemen of Tipperary, Galway, Mayo, Sligo, and Roscommon, and prescribed for general adoption across Ireland”. This consisted of 26 rules – I won’t list them all, but here is a taste:

The first offence requires the first apology, though the retort may have been more offensive than the insult. Example: A tells B he is impertinent, etc. B retorts that he lies; yet A must make the first apology, because he gave the first offence, and (after one fire) B may explain that retort by subsequent apology.

And you know that movie trope, where one of the duellists, his opponent’s shot having missed, simply fires his weapon into the air? That is a no-no:

No dumb firing, or firing in the air is admissible in any case. The challenger ought not to have challenged without receiving offence, and the challenged ought, if he gave offence, to have made an apology before he came on the ground; therefore children’s play must be dishonourable on one side or the other, and is accordingly prohibited.

If you were new to duelling then you could avail yourself of one of the handy guide books on the subject, such as The Art of Duelling, published in 1836 (pseudonymously by ‘A Traveller’). One’s morning routine is very important:

Let him drink the coffee, and take a biscuit with it, directly he rises: then, in washing his face, attend to bathing his eyes well with cold water. If in the habit of wearing flannel next the skin, he should omit putting it on. Wounds, comparatively trifling, have often become dangerous from parts of the flannel clothing being carried into them, particularly in warm climates. I do not advise his taking more than a biscuit and cup of coffee. To eat a hearty breakfast is wrong; I am not one of those who subscribe to the Italian opinion, that nothing can be well done by an Englishman unless his stomach is full of roast beef. The digestive organs are seldom prepared for the reception of food at such an unnatural hour as six or seven, and the brain would consequently be oppressed with the fumes proceeding from an unhealthy digestive process..

It is terribly embarrassing if you forget your guns:

He should observe that the pistol-case is furnished with caps and every other necessary, and see it put into the chaise himself; instances have occurred more than once, of the pistols being left behind in the confusion of starting, subjecting the parties, of course, to much inconvenience and ridicule.

It is wholly acceptable, nay encouraged, to have a little stiffener before the action starts:

While proceeding to the scene of action, if he feels himself nervous, or imagines that he is not sufficiently braced up for the encounter, he should stop and take a bottle of soda-water, flavoured with a small wine-glass of brandy: this will be found an excellent remedy, and, from experience, I can strongly recommend it as a most grateful stimulant and corrective.

The book goes on to provide some genuinely practical advice about making sure you present as small a target as possible for your opponent:

The risk in duelling may be considerably lessened by care in the manner of turning the body towards the adversary. I have often seen a raw inexperienced fellow expose his person most unnecessarily; standing with a full front towards his antagonist, and neglecting to bring down his arms, he offered the other party a much larger surface to fire at than the laws of duelling require, rendering, of course, the danger to himself greater.

Not everyone thought that this advice was useful. The British politician Charles James Fox (1749–1806) once fought a duel facing his enemy full-on because, he said, “I am as thick one way as the other.” You can judge the accuracy of that assertion yourselves:

In contrast, George Robert FitzGerald (1748–1786), aka ‘Fighting Fitzgerald’, was sufficiently adept at this approach that:

…he reduced his height five or six inches. His plan was to bend his head over his body until the upper portion of him resembled a bow. His right hand and arm were held out in front of his head in such a manner that the ball would have to pan all up his arm before it touched a vulnerable part.

This served Fitzgerald well – he won numerous duels before, err, being hanged for conspiracy to commit murder.

Hollywood would have use believe that virtually every duel ends in the death of one or other of the parties involved, and this was also a commonly held view when duelling was rampant, as ‘A Traveller’ notes:

Persons generally imagine when they hear a man is about to fight a duel that he must be killed; and nine men out of ten, upon receiving a challenge, make their will, and get no sleep the night previous to their going out – that is, in this country.

However the mysterious author is quick to disabuse this notion:

There are many parts of the body through which a ball may penetrate without the wound proving mortal. In Stapelton's affair with Moore, for example, the ball passed within half an inch of the heart, yet he recovered. Recovery, however, in such cases, depends much on the sufferer's habit of body, and strength of constitution.

Some of my acquaintances now living have received shots through the lungs and spleen. One, formerly an officer in the Hanoverian service, has been twice shot through the head; and, although, minus many of his teeth, and part of his jaw, he still survives, and enjoys good health.1

About five years ago, I took much pains to ascertain the result of nearly two hundred duels; and I found upon the average one out of fourteen had been killed, and one of out of six wounded.

As most men, even those who have been in combat, were unlikely to have had to fire a weapon accurately at a person a short distance away whilst that person is simultaneously firing back at them Traveller describes a (somewhat involved) training method:

The next matter of importance is, to accustom himself to receive the discharge of his antagonist without feeling nervous or uneasy: and to accomplish this, he should have the wooden figure of a man constructed and placed before his target, or in some other position where the balls can do no injury should they miss it. A strong bracket must be affixed to the shoulder, with two leather straps attached, and so disposed that they will firmly secure a pistol in the position it would appear if held by an adversary. A small hole should be bored in the fore part of the guard large enough to admit a piece of copper wire; one end of which is to be wound round the trigger, and the other made fast to a piece of whipcord about twelve yards long. To the other end of the whipcord a small hook should be affixed: and, the pistol being charged with a good charge of powder, rammed tight, the practitioner must take his station, hooking the end of the whipcord on the waist-band of his trowsers. Drawing himself firmly into position, he should raise his arm and fire, at the same moment receding slightly back, he will discharge the other pistol upon himself.

I have known persons some months before they could overcome that nervous sensation produced by being fired at. Constant practice, however, will overcome it sooner or later.

To be able to stand firm and unmoved while a pistol is discharged upon you, I consider quite as important as hitting the target cleverly.

I’ll close by talking about a few of the more interesting duellists and duels from history. The psychopath I alluded to earlier was the Chevalier d’Andrieux who had killed seventy-two men in duels before the age of thirty. We know of the number because one luckless opponent boasted to him, before things kicked off, “Chevalier, you will be the tenth man I have killed!” to which d’Andrieux replied “And you will be my seventy-second!”. Which shortly thereafter he was. Something he enjoyed was getting his subdued opponents to deny God, telling them that if they did, they would be spared. He would then promptly cut their throats, killing their fleshy bodies and immortal souls in a single blow.

There there was duel fought with blunderbusses in twin balloons 2,000 feet above Paris, which ended up with one duellist, and his luckless second, plummeting to their deaths. Except that, despite being mentioned on the TV show QI, it never happened but was the invention of a regional English newspaper!

I have referred to duellists as though they were solely men, but this was not the case. Though infrequent, women were fighting duels from at least the 18th century, such as this one which took place in Georgia in 1817:

Last week a point of honor was decided between two ladies near the South Carolina line, the cause of the quarrel being the usual one — love. The object of the rival affections of these fair champions was present on the field as the mutual arbiter in the dreadful combat, and he had the grief of beholding one of the suitors for his favor fall dangerously wounded before his eyes. The whole business was managed with all the decorum and inflexibility usually practised on such occasions, and the conqueror was immediately married to the innocent second, conformably to the previous conditions of the duel.

Not everyone is happy that duelling has been consigned to history. David L. Cohn, writing in The Atlantic in April 1945 made the case for its reintroduction. He was particularly irked at the weakness of libel laws in the USA and thought that duels could help solve the problem:

The remedy, then, is to revive dueling and put such safeguards around it as to prevent it from becoming the plaything of expert pistol shots in search of stronger diversion than softball games. Certainly no man should have the right to make an outright deal for a duel with another man. He must first present his case to a Court of Honor composed, say, of ten volunteer men and women of the community who are both levelheaded and persons of integrity. If they hold against him, he must retire and peacefully lick his wounds or hire a lawyer to present his grievances in court. But if they hold that he has been injured, he should then be permitted to challenge the offender by public notice in the local newspaper so that the community will be aware of it and become a party to it.

I am not wholly convinced that this would improve the quality of journalism, but it would be kind of interesting to test…

I think that this might be stretching the definition of ‘good health’ just a little bit.

fightin words