A history of… crisps (potato chips)

Including the "furious rejection" of the potato by the French people

(I hope our American readers will forgive me, but I will be using the British term crisps, rather than potato chips, throughout this piece.)

When researching the history of something it is a rare joy to discover that it has a clear, documented origin, such as is the case with crisps. In 1853 Cornelius Vanderbilt, the shipping and railway tycoon, was dining in Moon’s Lake House, a restaurant in the town of Saratoga Springs in New York state. And he had a problem with his food. With his potatoes, to be precise. They were too thickly sliced, insufficiently crisply fried and needed more salt! So he sent them back. A new portion arrived. Still too thick, still too limp, not salty enough. So they were sent back too. This went on until the chef, one George Crum, totally lost his patience. In a fit of pique he used a mandolin to slice the spuds into wafer-thin slices, fried them until they were nothing but crisp, doused them in salt, and sent them out to his discontented customer. To Crum’s amazement, Vanderbilt loved them, and the crisp was invented!

Except, of course, history is never quite that simple. One version of the story has it that it was actually Catherine Adkins Wicks, Crum’s sister, who did the frying (and this was so claimed in her obituary when she died at the grand old age of 103). But the details of who might have done the cooking are irrelevant. Vanderbilt was never there, and as we shall learn, crisps were around decades earlier than 1853. But before we get into that, let’s have a quick look at the history of the potato.

Wild potatoes can be found across a large swath of land stretching from the southern USA right down into southern Chile and were probably being cultivated in what is now Peru around 10,000 years ago. It is hard to be certain because, unlike tough grains, the soft, fleshy, nature of the potato makes it much less likely to be preserved, though confirmed remains have been dated back 4,500 years. The earliest known European encounter with the vegetable took place in 1537, as noted in a report by the conquistador Don Juan Castellanos. Initially the Europeans spurned this noble root – they considered it appropriate only for the local natives, rather than civilised men such as themselves. But this view changed as they began to appreciate its virtues, and it wasn’t long before they were stocking their ships with them to eat on the long voyages home.

At some point, probably around 1562, someone had the bright idea of planting a few of the uneaten tubers on the Canary Islands to see if they would grow, and by 1567 they were being shipped from the Canaries to Antwerp. Around the same time Basque fishermen introduced the potato to Ireland, where they landed after Atlantic fishing trips to dry their cod. Imported potatoes had actually been eaten in Europe before this point, as Lancelot de Casteau, the chef to the prince-bishops of the Principality of Liège served “boiled potatoes” in the third course of a banquet that he prepared on the 12th December 1557 to celebrate the “joyous entry” (the first official visit of a new royal to a city) of Prince-Bishop Robert of Berghes.1

In 1604 he went on to publish the earliest known potato recipes in Ouverture de cuisine:2

Boiled potatoes. Take a thoroughly washed potato and boil it in water; when it is ready, it needs to be cleaned, cut, greased with butter and pepper.

Otherwise: Cut the potato into slices as shown above, stew with Spanish wine, oil and nutmeg.

Take potato slices, stew them with butter, chopped marjoram and parsley; simultaneously whisk four or five egg yolks with a little wine, pour them into the boiling potatoes, remove from heat and serve.

Otherwise: Roast the potatoes like chestnuts in the ashes, peel and cut into slices. Sprinkle with chopped mint, pour boiled raisins, vinegar and sprinkle with pepper.

While a delicious array of potato dishes were being consumed in some European countries, other nations, particularly France, took a much dimmer view of the potato. Partly this was due to agricultural practices, but there were other factors at play as well. One was the view as they grew underground, and thus as far from heaven as any plant could get, that they were ungodly and only fit for animals. Another was that potatoes were poisonous, and specifically that they could cause leprosy! The potato is a member of the poisonous nightshade family – indeed its shoots and stems are very poisonous – but as I am sure you have all discovered the tubers are fine to eat. This belief was so widespread that in 1748 France actually passed a law prohibiting the cultivation of the potato. This law was finally repealed in 1772 due in no small part to the tireless efforts of one Antoine-Augustin Parmentier3 – pharmacist, agronomist, and creator of the first mandatory smallpox vaccination campaign.

Serving in the French army during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) Parmentier was fed potatoes after having been taken prisoner by the Prussians, and saw how their cultivation could benefit France, but he would have to get that law overturned…

What followed is best described as a series of stunts. He held potato-themed dinners to which invited the great and good, including Benjamin Franklin. He presented bouquets of potato flowers to the king and queen. Most famously of all, he planted a large patch of potatoes, and when it came time for them to be harvested, he mounted an armed guard around the plot. When the guards departed one evening the locals, convinced that the crop being so protected must be incredibly special, snuck in and dug up all of the potatoes!4

Potatoes remained unpopular in France for many years following the repeal of the law. So much so that in the appalling grain shortages in the run-up to the French Revolution of 1789 farmers still refused to grow the crop:

…most of the farmers, who are not sufficiently educated, follow mechanically and without reflection, the practice of their small township or the method of their old relatives. A new culture would require a tiring study… But in vain would one cultivate, in vain would one multiply this salutary commodity, if the people themselves, if the poorest citizens, stubborn of an absurd prejudice, refused, disdained to consume it. We have seen them, in times of the cruellest famine, rejecting the potato with fury, and shouting that we wanted to poison them.

Eventually Parmentier won his compatriots over, to the extent that when he died in 1813 potato plants were planted around his grave. Replacements are planted there each year to this day, and visitors leave potatoes on his tomb as marks of gratitude and respect.

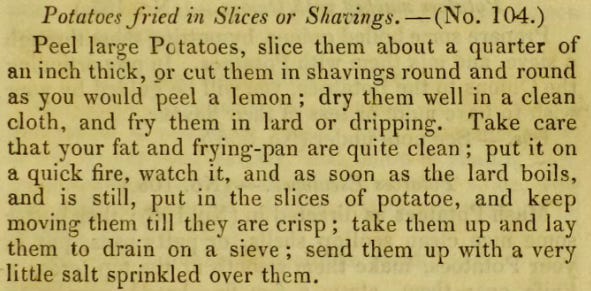

The first recipe for something akin to crisps can be found in in William Kitchiner's book The Cook's Oracle5 published in 1817:

While George Crum back in Saratoga clearly didn’t invent the crisp, he (or those working with him) played an important role in their popularisation in the second half of the 19th century. Crisps were served not as a mass-market snack food, but rather as a restaurant delicacy, though their fame really began to spread when he started selling them in take-out boxes labelled ‘Original Saratoga Chips’.

The person most widely credited with turning the humble crisp into a global snack food is one William Tappenden, who in 1895 moved crisps out of restaurants and into grocery stores. He began mass-producing crisps, initially in his home kitchen, and then in a barn, and delivering them by the barrel-load to local retailers. Many other ingenious entrepreneurs followed suit, and it wasn’t long before they could be found in every town in the country. Back then crisps were scooped from large bins in stores, and popped into wax-paper bags for the customer to take home with them. This was a far from ideal means of distribution, as the crisps at the bottom of the bins tended to get crushed become stale. It wasn’t until the 1920s that Laura Sudder hit upon the idea of pre-packaging crisps in their own individual bags prior to sale, thus investing the crisp packet. This was an incredibly successful innovation – the company that she founded, Laura Scudder Inc., was sold for $100 million in 1987.

At the start of the 20th century most crisps were sold unseasoned. Frank Smith, founder of Smith’s Crisps in the UK started adding little wraps of salt to his crisps in 1920, but it wasn’t until 1954 that the first truly flavoured crisps began to be sold. In 1954 Joe ‘Spud’ Murphy, owner of the Irish company Tayto, began selling cheese and onion flavoured crisps, and at around the same time barbeque flavoured crisps began being sold in the USA. British readers may be surprised to learn that salt and vinegar flavoured crisp, which most would consider to be the most traditional variety, only began to be sold nationally in 1967.

I cannot finish without a quick discussion of Pringles, one of the most popular global crisp brands. Except they are not crisps. They are made from an extruded dough which contains, in addition to potato products, wheat starch and corn flour, that is shaped into perfect, stackable, hyperbolic paraboloids. Though Pringles are not technically crisps (as they are not made from fried sliced of potato) they are, oddly, legally crisps. This was established in 2009 in the UK Court of Appeals because (there is not enough room here to explain why) if they were not crisps they would be exempt from a 20% sales tax. Lawyers for Pringles argued that their product did not possess an appropriate quality of “potatoness” to be deemed crisps. The judges rejected this on the basis that it was "an Aristotelian question" and ruled that a “reasonable man on the street” would consider them to be no different to crisps, and so they are subject to the tax.

Today total global crisp sales are around 50 billion dollars a year, weighing in at around five million tonnes, which equates to an astonishing 5 trillion individual crisps – or more than 600 for every person on Earth. And yes, that does include Pringles.

The most recent Joyous Entries were organised in honour of King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium in 2013.

Or, to give it its full title: Ouverture de cuisine. Finally! A 17th-century author who considers brevity to be virtue when it comes to book titles!

The dish “Parmentier potatoes” is named in his honour.

It would be remiss of me not to mention that the same stunt is said to have been carried out by Frederick the Great, but it possible that Parmentier stole the idea from him.

Or to give it its full title: The Cook's Oracle: Containing Receipts for Plain Cookery on the Most Economical Plan for Private Families, Also the Art of Composing the Most Simple, and Most Highly Finished Broths, Gravies, Soups, Sauces, Store Sauces, and Flavouring Essences : the Quantity of Each Article is Accurately Stated by Weight and Measure, the Whole Being the Result of Actual Experiments Instituted in the Kitchen of a Physician. Which is a bit of a mouthful.

I have a sudden desire to go out and buy a packet of crisps, lol.

Wonderful article. I do enjoy crisps, but perhaps they should have remained a delicacy and save us all from some extra kilocalories.

I think this is a well written and researched article. It it is a lovely demonstration that the history of every day items is intriguing.