For, oh, at least 20 years I wore blue jeans every day (or at least every day that I didn’t have to conform to workplace dress code, and even then I would normally change into them as soon as I got home). Such was their ubiquity I never thought to wonder where they originated from, or indeed, why they were blue. It turns out that they have a much longer, and more interesting, history than I had been expecting…

The story of jeans begins in the textile workshops of Genoa (in what is now Italy) and Nîmes (in southern France). In those trading cities of the 16th–17th centuries, weavers produced a coarse, twill-woven cotton known simply as jean or jeane (or ‘jean fustians’, fustian being the name given to heavy, woven, cotton fabric). The word ‘jeans’ itself almost certainly comes from the French word Gênes, meaning ‘Genoa’. The fabric, and the name, spread quickly – the UK National Archives records that in 1576, a quantity of ‘jean fustians’ arrived into the port of Barnstaple. This fabric, described as being of “medium quality and reasonable cost” was more akin to corduroy than the stuff that we wear on our legs today, and was used for everyday work clothes due to its hard-wearing nature – indeed the Genoan navy was outfitted in jeans material, because it could be worn both wet and dry.

These clothes were dyed blue, very much like ours today, using indigo dye from the plant Indigofera tinctoria. Indigo had been used as a dye in south Asia for millennia and European colonisation of the subcontinent resulted in much greater commercial cultivation and export. At the same time the colonial powers introduced it as a cash crop in the Americas – with Spain starting to cultivate indigo in Central America in the 16th century, and France on the island of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in the 17th century. So indigo was cheap, the blue colour helped to conceal stains and also it was more colourfast than other dyes. Indigo is not soluble in water, rather than being absorbed by the fabric fibres it forms a solid layer on their surface – which makes it very hard for it to be washed out. It can though, as you will have doubtless seen, gradually rub off the fibres through wear, a process called ‘crocking’.1

Now you might think that everyone would be happy about this cheap, useful, dye pouring to Europe, but you would be wrong; the woad producers were very unhappy indeed! Woad is a traditional blue dye made from the plant Isatis tinctoria (a member of the cabbage family) for thousands of years. The Roman historian Tacitus famously claimed that the ancient Britons would even use it on themselves:2

All the Britons dye themselves with woad, which produces a bluish colour, and gives them a more terrible appearance in battle.

Woad is simply a worse dye than indigo, however thousands of people were involved in its production, distribution and use – people whose jobs would be swept away by the tide of indigo. These people had significant power and influence, and so anti-indigo campaigns sprang up. They were most successful in France, where, in 1609, King Henry IV passed an edict banning the stuff, referring to it as ‘teinture du diable’ (the ‘devil’s dye’) with claims being made that it burnt and corrupted fabrics.

Indigo was, however, just too good and too cheap for these measures to hold it back for long, and the popularity of blue jean fabric among the working classes can be most strikingly seen in the work of an anonymous artist working in the Lombardy region of what is now Italy between 1675 and 1700. The ‘Master of the Blue Jeans’ was only identified as a distinc artistic figure in the early 2000s when Gerlinde Gruber, a curator at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, recognized that a number of 17th-century paintings – scenes of everyday life depicting figures wearing striking blue garments – shared a consistent style and thematic focus. I have to say that when I first saw his pictures I was totally blown away.3 There is a young boy wearing a blue jeans jacket4 that would not look out of place today:

And a woman wearing a jeans skirt similar to dozens I have seen people wearing:

I particularly love the fact that these clothes are shown to be ageing, to be tearing and crocking, just like the jeans that I have worn. The sharp-eyed among you may have noticed that these fabrics are not quite the same as the ones that we wear today. The twill weave (whereby the horizontal ‘weft’ yarn goes over and under multiple vertical ‘warp’ yarns to create a diagonal ribbed pattern) that the Genoans used was very simple. Towards the end of the 16th century, weavers in the French city of Nîmes decided to start working with cotton as well as their traditional wools and silks (most likely to have a piece of the market the Genoans had created). They wove a tighter 3/1 diagonal twill that was tougher than the one that they were imitating and crucially they used indigo-dyed warp yarns and white weft yarns that created a distinctive pattination which is identical to the jeans that we wear today.5 This fabric was known as serge de Nîmes and then simply ‘de Nîmes’ which in time was shortened further to ‘denim’.

At around the same time course cotton cloth, similar to that from Genoa, was being produced in India, around Dongri, a dockside village near Mumbai. This too was dyed with indigo, and was named, after its origins ‘ḍūngarī’. The cloth was used for all manner of work clothing but in time became particularly associated with bibbed overalls. These overalls took on the Anglicised name of the cloth they were made from, which from at least as early as 1605 been called ‘dungaree’ – I suspect few people wearing dungarees today would realise the age and origin of the name of their clothing!

The specific term ‘blue jeans’ is generally thought6 to have originated not in USA as perhaps one might have expected, but with a Swiss banker in Genoa. In 1800 the city was controlled by French revolutionary troops under the command of André Masséna and Jean-Gabriel Eynard (1775–1863) won the contract to supply the soldiers with uniforms. This he did, making from fabric he referred to as ‘bleu de Genes’, or what we would now call ‘blue jeans’.

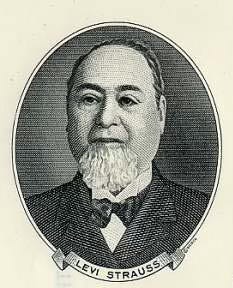

It was, however, in America that a critical invention was made that helped propel jeans to global dominance. In the second half of the 19th-century California’s Gold Rush turned create a new, vast, market for work clothes and goods as workers flooded into the state. One person to grasp this opportunity was Levi Strauss (born Loeb Strauss, 1829–1902), a Bavarian-born immigrant. In 1853, at age 24, Levi sailed from New York to San Francisco to open a branch of his family’s New York dry-goods business. San Francisco was full of prospectors in need of sturdy gear, and Strauss sold them, tents, blankets, and crucially, work pants. The legend (or myth) says his workers initially made trousers from coarse tent canvas, but miners complained these rubbed too harshly. So Levi switched to the dyed twill cloth serge de Nîmes imported from France. As a history of the company puts it, Strauss “substituted a twilled cotton cloth from France called ‘sergé de Nîmes.’ The fabric later became known as denim and the pants were nicknamed blue jeans”.7 Thus by the late 1850s Strauss was selling blue cotton waist-pants under his San Francisco ‘Levi Strauss’ label.

A tailor named Jacob W. Davis (1831–1908), originally from Latvia, was also at work in the West. Stationed in Nevada, Davis was sewing work trousers by 1870 and like many tailors he bought cloth bolts from Strauss’s dry-goods house. He noticed, as he later recounted in his patent filing, that seams would ‘rip or start’ at pocket corners when men tugged into their pockets To solve this, Davis devised a clever fix: he would secure each pocket-opening corner with a copper rivet, embedding the metal into the fabric to ‘bind the two parts of cloth… together’ and take the stress off the thread. His invention “consists in the employment of a metal rivet or eyelet at each edge of the pocket-opening, to prevent the ripping of the seam at those points”. In 1872 Davis wrote to Levi Strauss proposing they patent the idea together. Strauss agreed, and on May 20, 1873 they were granted U.S. Patent No. 139,121 for ‘an Improvement in Fastening Pocket-Openings’. The patent’s text described the new garment: ‘a pair of pantaloons having the pocket-openings secured at each edge by means of rivets… whereby the seams at the points named are prevented from ripping’. Riveted denim pants were born – the first true, modern, blue jeans.

In order to distinguish Levi jeans from those made by competitors Davis started sewing a distinctive double orange threaded design on their back pockets, which was soon trademarked and remains on Levis to this day. His original jeans had three pockets, two side pockets and one rear pocket on the right-hand side. These jeans were known by their lot number – 501 – and the company worked hard to push this name as brand that indicated quality. This was vital for their ongoing success, as their original patent was only for 17 years and expired in 1890, allowing competitors to launch their own versions. 501s, as they continue to be known, gained a second back pocket in 1901 and a front-right watch pocket shortly afterwards. Belt loops came in 1922, and a few tweaks have been made since then, but the jeans that sell around ten million pairs a year today are basically the same as the ones sold a century ago.

The final major development in the story of jeans came in 1934 when Levi launched the 701, a jean specifically design for women. Women working on ranches had taken to wearing men’s jeans for their practicality, but for obvious reasons the fit wasn’t great. The 701 was shaped for women’s figures, had a high-rise waist, and, progressively for the time, had a similar button fly.

So why are the jeans that we wear today still, mostly, blue, when so many other colours are available? In part it is due to the indigo dye (which has been synthetic for more than a century) whose crocking creates that lived-in look but mostly it seems to be simply tradition, and the fact that the terms blue and denim are more or less synonymous. As I sit writing this wearing a pair of blue jeans, knowing that their history stretches back centuries, then that seems like a pretty good reason to me…

I was delighted to learn that this is the word for it!

Though it is quite possible that he just made this up.

Finding things like this is one of the reasons I love writing these pieces.

I lightened this image a little as the original was very dark, but otherwise it is unchanged.

It turns out that twills are quite involved, I think that this is an adequate explanation.

I’ll be honest this story is quite hard to substantiate.

Though as we know the term is older than that, this story has almost certainly been ‘creatively enhanced’.

Leave it to Julia! Who knew? Such an interesting article! Now can I not only wear my jeans in comfort, I will also wear them with pride!

When my very elderly and persnickety Southern grandfather first saw me wearing jeans when I was young, he sharply complained that I looked too common. I was making a statement, according to his values from a very different time, that I was a worker’s daughter and therefore wearing blue jeans was insulting to our family. Fashion? Not to him! He was a mountain guide for the Univ of Arizona geology team and always started each journey in freshly laundered and ironed, earth-colored, quality chinos with a matching ballcap for hiking. Never denim even though he was often trekking in the most desolate regions for weeks at a time. How fashions do change!