A history of… ancient elections

The election of the Doge of Venice was very complicated indeed!

Human civilisation can probably be traced back to the foundation of the city of Çatalhöyük (sited in modern day Turkey) around 9,500 years ago and for most of that time most people had no say in the choice of those that ruled them. Power was variously acquired through birth, combat, cunning, wealth and religious status (and often a combination of these factors) by an array of kings, queens, emperors, tyrants, dictators and religious leaders. But that it not the case today, or at least not everywhere (the Economist Democracy Index calculates that only around 60% of people today live in something approaching a democracy) and with the UK and France about to go to the polls and the USA not long afterwards, I thought it would be interesting to have a look at some ancient elections and electioneering.

The earliest example of something approaching what we would consider a democracy dates back to 508–507 BC in the city-state of Athens (it is no coincidence that the word ‘democracy’ comes from the Greek words dêmos (common people) and krátos (force/might). Athens had been ruled by a cabal of aristocrats, before falling under the power of two tyrants: Pisistratus followed by his son Hippias. In 510 BC the Athenians enlisted the help of Cleomenes, the King of Sparta, to remove Hippias, which he duly did – only to replace him with a pro-Spartan oligarchy.

A lawmaker named Cleisthenes was having none of that. He set up a new system to replace the oligarchy starting by dividing the state into ten areas, called demes. Every male citizen over the age of 18 had to register in their deme, and could then be selected by lot to serve in one of a thousand or so posts of government. Crucially however, there were around a further 100 posts whose office holders were selected by election. These roles included ten generals (fairly obviously it made sense to select people who had some military experience, rather than rely upon the skills of a group of randomly chosen people) and those in roles that involved control over money. This latter group was included so that if it turned out that they had embezzled any money it could be clawed back from them afterwards – hence it made sense for them to be rich!

This was far from a perfect system – women were unable to vote or hold office for starters – but it did involve people running for public office and being selected by election. Plato, it is fair to say, was not a fan of this system (he was more fond of absolutist power being held by ‘philosopher kings’) and had a few choice things to say on the matter:

A delightful form of government, anarchic and motley, assigning a kind of equality indiscriminately to equals and unequals alike!

Democracy does not contain any force which will check the constant tendency to put more and more on the public payroll. The state is like a hive of bees in which the drones display, multiply and starve the workers so the idlers will consume the food and the workers will perish.

Dictatorship naturally arises out of democracy, and the most aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme liberty.

Cleomenes of Sparta was also none too impressed, and tried to bring back the tyrant Hippias, but failed to reinstate him and the system remained in place (with a few bumps along the road) for 180 years.

Meanwhile democracy was also developing in ancient Rome. There (again male) citizens were divided into centuries – groups of 100 people – each of which had a single vote for the key offices of power and important decisions. The members of the century would vote to agree how their representative would vote, then the representatives from each century would vote (and there were as many as 373 of them) and the majority selection would prevail. In theory therefore everyone had an equal vote, in practice however things were a little messier. Some of the centuries, err, ended up having fewer than 100 people (amazingly these were the centuries comprising the wealthiest people!) so each of their members had more of a say. Despite this flaw, anyone who wanted to get elected to an office, particularly the roles with the most power, the consuls, would have to do a fair amount of electioneering.

Candidates would have between 17 and 25 days between the announcement of the election and it taking place, and would spend much of that time in the forum trying to win over the electorate. Some would be accompanied by a slave specifically trained to remember the names of key citizens and whisper them in the candidate’s ear so that they could pretend to know them (such slaves were called nomenclators from which we get the word ‘nomenclature’). To make themselves stand out the people running for office would wear a specially whitened toga, a toga candida, from which the word ‘candidate’ is derived.

When Marcus Tullius Cicero decided to run for the office of consul in 64 BC he faced a challenge. Although he was an excellent speaker, and fairly well known, he was a total newbie when it came to the world of politics. To help him out his brother, Quintus Tullius Cicero, wrote up some advice in Commentariolum Petitionis (the Little Handbook on Electioneering) and much of it is still relevant for campaigns being run 2,000 years later!1

Firstly, make sure that people with power are on your side:

It is a point in your favour that you should be thought worthy of this position and rank by the very men to whose position and rank you are wishing to attain. All these men must be canvassed with care, agents must be sent to them… furthermore, take pains to get on your side the young men of high rank, or retain the affection of those you already have. They will contribute much to your political position. You have very many; make them feel how much you think depends on them: if you induce those to be positively eager who are merely not disinclined, they will be of very great advantage to you.

Next, dig up the dirt on your rivals and make sure that it is widely known. Of Gaius Antonius Hybrida he says:

We know that he was ejected from the senate by the judgement of genuine censors: in our praetorship we had him as a competitor, with such men as Sabidius and Panthera to back him, because he had no one else to appear for him at the scrutiny. Yet in this office he bought a mistress from the slave market whom he kept openly at his house. Moreover, in his canvass for the consulship, he has preferred to be robbing all the innkeepers, under the disgraceful pretext of a libera legatio, rather than to be in town and supplicate the Roman people.

And he doesn’t hold back when talking about the other opposing candidate, Lucius Sergius Catilina:

Good heavens what is his distinction? Is he of equally noble birth? No. Is he richer? No. In manliness, then? How do you make that out? Why, because while the former fears his own shadow, this man does not even fear the laws!—A man born in the house of a bankrupt father, nurtured in the society of an abandoned sister, grown to manhood amidst the massacre of fellow citizens, whose first entrance to public life was made by the slaughter of Roman knights. For Sulla had specially selected Catiline to command that band of Gauls which we remember, who shore off the heads of the Titinii and Nannii and Tanusii: and while with them he killed with his own hands the best man of the day, his own sister’s husband, Quintus Caecilius, who was a Roman eques, a man belonging to no party, always quiet by inclination, and then so from age also.

He also notes that now is not the time to be particular about the people you hang out with:

But although you ought to rely on and be fortified by, friendships already gained and firmly secured, yet in the course of the canvass itself very numerous and useful friendships are acquired. For among its annoyances a candidature has this advantage: you can without loss of dignity, as you cannot in other affairs of life, admit whomsoever you choose to your friendship to whom if you were at any other time to offer your society, you would be thought guilty of an eccentricity; whereas during a canvass, if you don’t do so with many, and take pains about it besides, you would be thought to be no use as a candidate at all.

Finally, it would be best for Cicero, if he wants to win, to go against his better nature and make promises even though he has no intention of keeping them:

For men desire not only to have promises made them, especially in their applications to a candidate, but to have them made in a liberal and complimentary manner. Accordingly, it is an easy rule to make, that you should indicate that whatever you are going to do you will do with heartiness and pleasure; it is somewhat more difficult, and rather a concession to the necessities of the moment than to your inclination, that when you cannot do a thing you should [either promise] or put your refusal pleasantly: the latter is the conduct of a good man, the former of a good candidate

The advice seems to have worked – Cicero was elected with the support of all of the centuries!

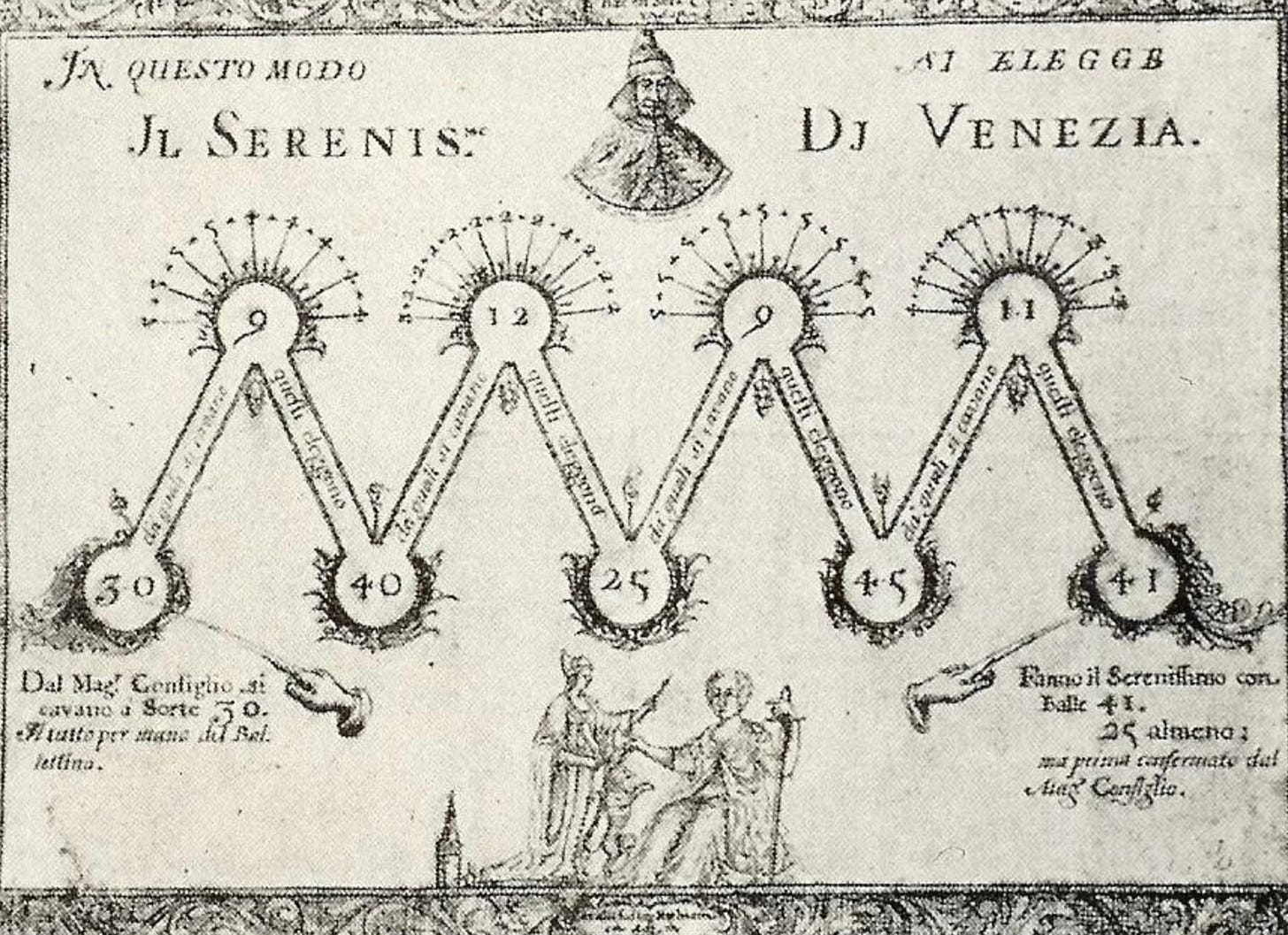

I’d like to end by talking about one of the oddest systems of election ever to have occurred in human history. The Doges were the rulers of Venice for more than 1,000 years. Elected for life, they wielded incredible power in their roles, and so it was important that these elections were not subject to bias or rigging. To achieve this a somewhat complicated system was put in place in 1268 and it continued to 1797. Here’s how it worked:

The great council would come together and the names of all of the councillors over the age of 30 were placed in an urn.

The youngest councillor would take the urn out into the square and have the first boy he saw select 30 councillors at random from it.

From this group of 30, 9 councillors were then chosen at random.

The group of 9 would then meet and select a group of 40 councillors from the council, each one had to be supported by at least 7 of the 9.

A system of ballots would randomly reduce these 40 to 12.

These 12 would then select a group of 25 with each person receiving the votes of at least 9 out of the 12.

Those 25 were randomly reduced by ballot to 9.

Those 9 then chose a group of 45 each of which had to have at least 7 votes.

Those 45 were reduced at random to 11.

The 11 selected a group of 41.

Each of the 41 then selected a candidate for Doge.

Each of the 41 voted for every candidate that they thought was suitable.

The candidate with the most votes (assuming that they had over 25) was then elected Doge!

There were additional safeguards in place – people could not vote for family members, and no group could contain more than one member of the same noble family. Luckily there exists a handy chart to show how it all worked (and we think modern politics gets complicated at times!).

There is some debate about the actual authorship and date, one view being that it was actually written post hoc early in the first century AD. Either way, it is a fascinating read!

I was dimly aware that the election of a doge was an arcane process, but I didn't know the half of it!

Apparently, in ancient China, when a vote was held on a major issue (such as whether or not to go to war), councillors would place either a black or white pebble in an urn. When the pebbles were counted, it was not the number of’ford’ or’againsts’ that mattered / it was which number was the luckiest!