Beer is the most popular alcoholic drink in the world, with almost 200 billion litres of the stuff consumed every year (indeed, it is the fourth most popular drink overall after water, coffee and tea). It is perhaps unsurprising then that it has a very ancient history – probably the oldest history of any alcoholic drink – and that is what I will be exploring in this week’s post.

The very earliest, Neolithic, beers were almost certainly made in Africa, from grains such as sorghum and millet, but as the brewing vessels would most likely have been made from animal skins no evidence for them survives. The earliest physical traces we have found date back an astonishing 13,000 years and were found in the Raqefet cave on Mount Carmel in Israel. Residues of fermented wheat and barley were identified on stone mortars, suggesting that these grains were crushed to make a mash which was then brewed to form a thick, porridge-like beer.

Similar evidence has been found in the 7,000-year-old site of Godin Tepe in modern-day Iran, while in Asia there is evidence from 9,000 years ago that a form of beer was being made in ancient China from rice, flavoured with honey and fruits. Meanwhile, far in the north, at the Skara Brae site in the Orkney Islands of Scotland, brewing was taking place more than 5,000 years ago. Beer was not invented just once; rather it seems that almost every culture that had grains figured out that they could be turned into booze. Even the Americas, which lacked wheat and barley until the Columbian Exchange, had their own version of beer. Chicha1 (or corn beer) is made from maize that is either malted in a similar way to barley or alternatively it is chewed so that enzymes from saliva break the starches down into sugars.

The earliest written evidence for the existence of beer is more than 4,000 years old and takes the form of a receipt found on the site of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur (located in modern-day Iraq). The ‘Alulu beer receipt’ provides us with wonderfully specific information about the world's earliest known drinks transaction. It was written during the 45th year of the reign of Shulgi, the King of Ur (2050 BCE) – we can be sure of this because the scribe who wrote it, Ur-Amma, signed and dated it! The text translates as “Ur-Amma acknowledges receiving from his brewer, Alulu, 5 sila [about 4 ½ litres or eight pints] of the ‘best’ beer”.

It is around the same time that we find the first literary reference to beer. The Epic of Gilgamesh is the world’s oldest known story, the earliest known physical fragments of which date back 3,800 years (but the story itself is probably several hundred years older). It tells the tale of Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk, and Enkidu, a ‘wild man’ sent down by the gods to stop Gilgamesh oppressing his people. Enkidu is civilised by Shamhat, a harimtu (sacred temple prostitute), through a combination of beer (and, err, sex but let’s not get into that):

Shamhat spoke to Enkidu, saying,

‘Eat the bread, Enkidu, it is the staff of life;

Drink the beer, as is the custom of the land.’

Enkidu ate until he was full,

Drank the beer—seven cups—and his heart grew light,

His face glowed, and he sang out with joy.

He was bathed and anointed, and became fully human.

From the same time we have the first recorded beer recipe (albeit in somewhat poetical form) written in a hymn to the Sumerian goddess of beer and brewing, Ninkasi:

Ninkasi, you are the one who handles the dough [and] with a big shovel, mixing it with sweet aromatics.

You are the one who bakes the bappir [barley bread] in the big oven,

Puts in order the piles of hulled grains.Ninkasi, you are the one who waters the malt set on the ground,

The noble dogs keep watch over the grains.

You are the one who soaks the malt in a jar,

The waves rise, the waves fall.Ninkasi, you are the one who spreads the cooked mash on large reed mats,

Coolness overcomes.

You are the one who holds with both hands the great sweet wort,

Brewing it with honey [and] wine.Ninkasi, you are the one who pours out the filtered beer of the collector vat,

It is [like] the onrush of the Tigris and Euphrates.

This pretty accurately describes the process of malting by which barley is partially germinated in order for the starch they contain to be converted into fermentable sugars. The grains are moistened and spread out to germinate, then boiled to release the sugars, and finally cooled prior to fermentation, as the hot mash would kill the yeast. Clearly rats and mice were a problem hence the need for the “noble dogs”!

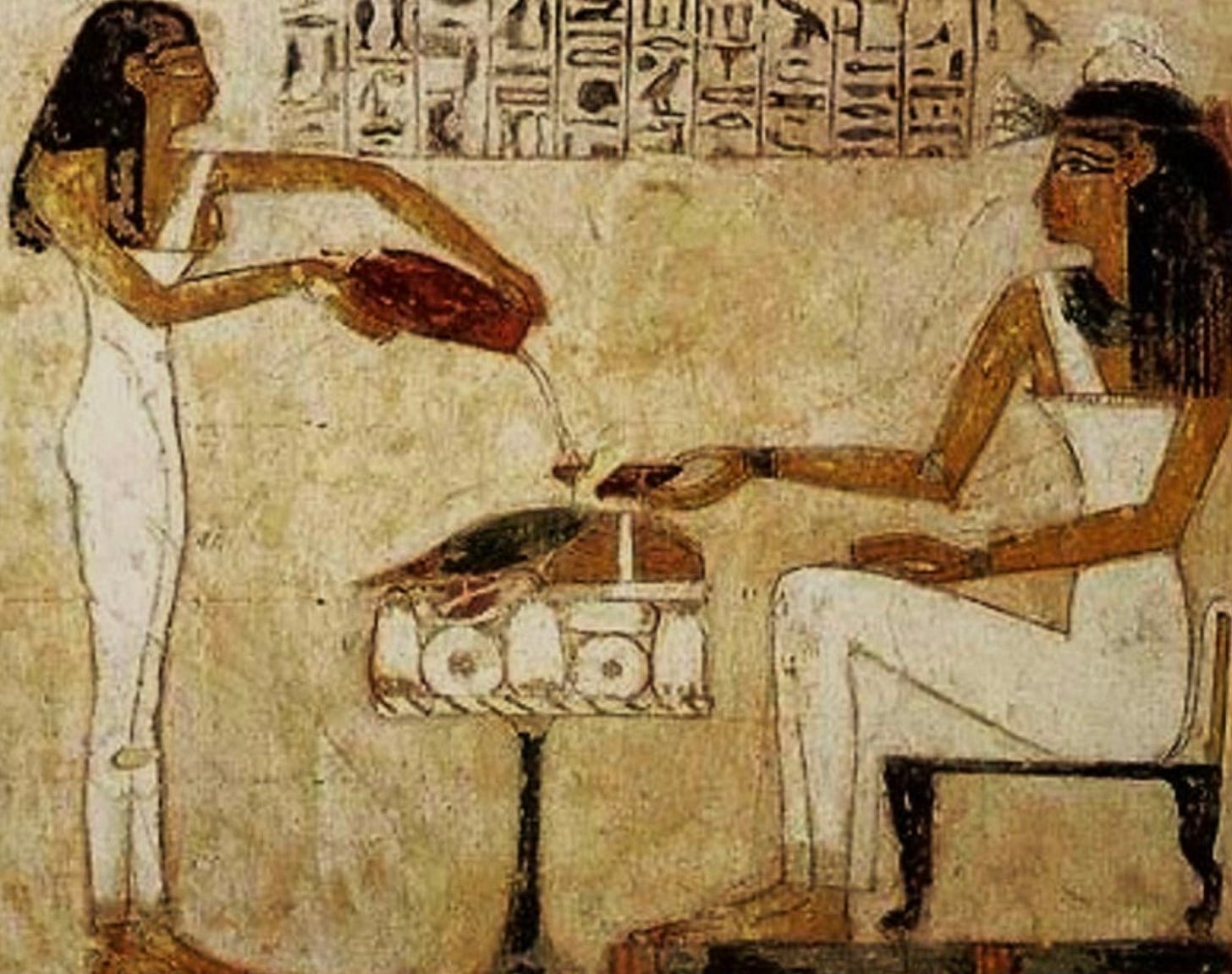

A short distance to the west, in Ancient Egypt, beer wasn’t simply something to be consumed to lighten one’s heart – it was a cornerstone of their civilisation. Building the pyramids took a lot of work, and beer was an essential part of the diet that ensured the workers were well-nourished. Records found in the village of Deir el-Medina where labourers lived when building the royal tombs of the New Kingdom (1570–1070 BCE) documents their rations:

Three loaves of bread and two jars of beer for each worker per day

It is hard to be precise about how large these jars were, but this was probably around five litres (nine pints) of beer each per day. It is important to note that this beer was almost certainly not as strong as beers today (had it been then the building of the pyramids would have been even more remarkable) and also that it was a much more substantial, unfiltered drink with the remains of the fermentation mash still in it. As I mentioned in my piece on drinking straws, this was often drunk, you guessed it, through straws, as this 3,300 year-old image of a Syrian mercenary shows:

Beer for the Egyptians was not just nutritional and recreational, it was also medicinal. The Ebers Papyrus (dating from 1,500 BCE) is the best-known record of ancient Egyptian medicine and mentions beer a couple of times. For example one can:

Chew bits of berry along with beer and it will relieve the constipation

Or to address the more serious problem of diabetes:

Drink a mixture including elderberry, asit plant fibres, milk, beer-swill, cucumber flowers, and green dates.

The efficacy of these remedies is perhaps open to question, not least given that the cure for blindness in the same document is:

Use two eyes of a pig with the water removed from them, true collyrium, red lead, and wild honey to create a powder and inject it into the ear. While mixing you must repeat “I HAVE BROUGHT THIS THING AND PUT IT IN ITS PLACE. THE CROCODILE IS WEAK AND POWERLESS.” (Twice)

Beer also played a role in Egyptian mythology, most notably in the ‘Destruction of Mankind’ section of The Book of Heavenly Cow (approximately 1,500 BCE). In it the Sun God Ra, irked at humanity’s disrespect, selects his daughter, Hathor, to become the ‘Eye of Ra’, take on the wrathful form of Sekhmet and go down to Earth to sort things out. She takes to this role with enthusiasm, slaughtering humans and wading through (and drinking) their blood. So much so that Ra realises that perhaps she has gone a bit too far and so needs to come up with a plan to rein Sekhmet in somewhat. His solution was to dye a lot of beer red and hope that she would drink it, mistaking it for human blood, and that this would calm her down a bit. And it worked:

Ra ordered his servants to brew beer mixed with ochre, seven thousand2 jars of it. They poured it over the fields, and Sekhmet drank deeply. She became drunk and forgot her rage.

In ancient Greece wine was very much the go-to drink, but though they were certainly had beer, called zythos, which was mainly the preserve of peasants and slaves. Herodotus (c.484–425 BCE) notes in his Histories that the Egyptians made beer in a similar way to mead:

πίνειν δὲ οἶνον αὐτοῖσιν οὐ νόμος ἐστὶ τῇ χώρῃ, κριθῆς δὲ πέμματα μέλιτος τρόπῳ πεποιημένον πίνουσιν (It is not customary for them [the Egyptians] to drink wine in their land, but they drink a barley drink prepared in the manner of honey.)

The ancient Romans were, I think it is fair to say, a bit sniffy about beer. They considered it to be very much the drink of northern barbarians and quite inferior to the wines consumed by sophisticated Mediterranean civilisations, though it did become adopted by the Roman army from that lands that they conquered. A typical critic was Aulus Gellius (125–184 CE) who wrote:

In Gallis, Germanis, aliisque barbaris moris est cerevisiam potare pro vino, quod potus cum sit sitim sedet, tamen laetitiam et elegantiam vini non habet. (Among the Gauls, the Germans, and other barbarian peoples, it is customary to drink the barley liquor [cerevisia] in place of wine, which, though it quenches thirst, lacks the joy and refinement of wine.)

Pliny the Elder (23/24–79 CE) also writes, despairingly, of the inclination of other races to make booze from grains (when grapes could be used) and also, somewhat strangely, their reluctance to dilute the resulting concoction:

The people of the Western world have also their intoxicating drinks, made from corn steeped in water. These beverages are prepared in different ways throughout Gaul and the provinces of Spain; under different names, too, though in their results they are the same. The Spanish provinces have even taught us the fact that these liquors are capable of being kept till they have attained a considerable age. Egypt, too, has invented for its use a very similar beverage made from corn; indeed, in no part of the world is drunkenness ever at a loss. And then, besides, they take these drinks unmixed, and do not dilute them with water, the way that wine is modified; and yet, by Hercules! one really might have supposed that there the earth produced nothing but corn for the people’s use.

The characterisation of beer as an unsophisticated drink, created only for drunkenness, appears to be somewhat unfair, and based very much upon the prejudices of the ‘civilised’ Romans. Archeological evidence has shown that rather than being crude brews, the Gallic and Celtic beers were flavoured with herbs and honey – there was clearly an art to their creation and a savouring of the results. It also seems likely that beer played a ceremonial role in the religious ceremonies of these peoples.

Durrington Walls is a large Neolithic settlement some three kilometres (two miles) north-east of Stonehenge that was inhabited between 2,800 and 2,100 BCE. While it may not have been a ritualistic site itself it was almost certainly played a supporting function for the rituals that took place close by. A number of excavated floors at Durrington Walls had been kept scrupulously clean by their owners, for use as malting surfaces for brewing. So, surprising as it might seem, when the ancient Britons greeted the rising sun on the morning of the summer solstice, surrounding by that amazing stone circle, they almost certainly did so with a beer in their hand!

Before you rush off for a cheeky beer, a quick question for you…

I have drunk Chicha in Bogota and it was pretty tasty. I suspect that it probably wasn’t prepared by the chewing method though.

Sekhmet needed a thousand times as much beer as Enkidu, I note!