Today in history: December 19

A famous flotilla, a brutal battle, a mild-mannered murderer?

This week’s little stories from contemporary historical sources…

Planning to stay, 1606

In 1606, the newly formed Virginia Company of London received a royal charter from James I to plant a colony in North America: what would become Jamestown. The company organised an expedition in three small ships – Susan Constant, Godspeed and Discovery – which finally left London on December 19 with around 100–140 colonists aboard.

Just before and during their departure window, the company’s London council drafted and added a set of detailed directions, usually called ‘Instructions given by way of advice … for the intended voyage to Virginia’, to guide the leaders once they made landfall. These instructions give us an idea about what the planners thought, said and feared in the days before they set off. Here are a few extracts:

When it shall please God to send you on the coast of Virginia, you shall do your best endeavour to find out a safe port in the entrance of some navigable river, making choice of such a one as runneth farthest into the land, and if you happen to discover diverse portable rivers, and amongst them any one that hath two main branches, if the difference be not great, make choice of that which bendeth most toward the North-west for that way you shall soonest find the other sea…

When you have discovered as far up the river as you mean to plant yourselves, and landed your victuals and munitions; to the end that every man may know know his charge, you shall do well to divide your six score men into three parts: whereof one party of them you may appoint to fortify and build, of which your first work must be your storehouse for victuals; the other[s] you may employ in preparing your ground and sowing your corn and roots; the other ten of these forty you must leave as sentinel at the haven’s mouth.

The other forty you may employ for two months in discovery of the river above you, and on the country about you…

In all your passages you must have great care not to offend the naturals, if you can eschew it; and imploy some few of your company to trade with them for corn and all other lasting victuals if [they] have any: and this you must do before that they perceive you mean to plant among them; for not being sure how your own seed corn will prosper the first year, to avoid the danger of famine, use and endeavour to store yourselves of the country corn…

You must take especial care that you choose a seat for habitation that shall not be over burdened with woods near your town: for all the men you have, shall not be able to cleanse twenty acres a year; besides that it may serve for a covert for your enemies round about.

Neither must you plant in a low or moist place, because it will prove unhealthful. You shall judge of the good air by the people; for some part of that coast where the lands are low, have their people blear eyed, and with swollen bellies and legs: but if the naturals be strong and clean made, it is a true sign of a wholesome soil.

Later, Captain John Smith (who was actually charged with mutiny on the voyage but later went on to become one of the leaders of the colony) recalled in his 1624 Generall Historie of Virginia:

On the 19 of December, 1606. we set sail from Blackwall, but by unprosperous winds, were kept six weeks in the sight of England; all which time, Mr. Hunt our Preacher, was so weak and sick, that few expected his recovery…

The three ships eventually cleared England and struggled through winter storms across the Atlantic. After months at sea, they finally reached the Chesapeake in April 1607 and chose Jamestown Island as the settlement site in May.

The Instructions shaped their early choices – in some ways for the worse. The insistence on a defensible, river-island location contributed to Jamestown’s unhealthy, brackish-water site; admonitions to keep settlers armed and wary helped frame relations with Powhatan peoples in a wary, militarised way from the start. But over the longer term, this tiny flotilla of December 1606 became the seed of English North America.

Planning to attack, 1675

Nearly 70 years later, those relations with “the naturals” were fraught at times. King Philip’s War (1675–76), named after the Wampanoag leader Metacom (called “Philip” by the English), was one of the bloodiest conflicts in 17th-century New England. By late 1675, after a devastating campaign of raids and counter-raids, colonial leaders believed the Narragansett people were secretly aiding Philip.

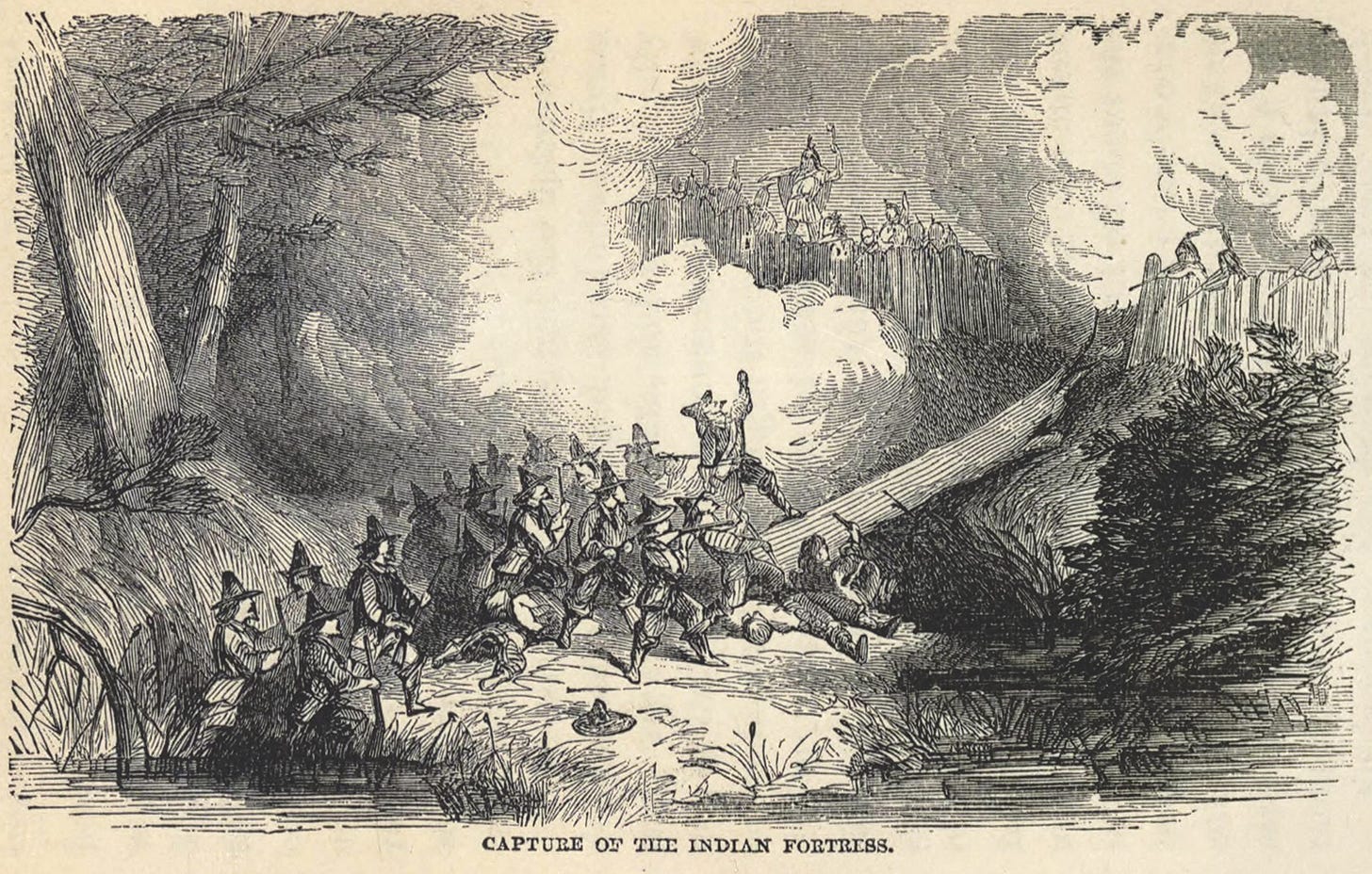

On December 19, 1675 – 350 years ago today – a force of roughly 1,000 colonial militia from Massachusetts, Connecticut and Plymouth, plus Native allies, attacked a large Narragansett fort in a frozen swamp in what is now South County, Rhode Island. The battle – or massacre – left hundreds of Narragansett people, including many non-combatants, dead, and heavy losses among the colonial troops as well.

Written only days after the battle, the anonymous pamphlet ‘A Farther Brief and True Narration of the Great Swamp Fight in the Narragansett Country December 19, 1675’ (probably written by a colonial officer or minister) gives a blow-by-blow account of the brutal assault.

On the 19th, although it was Sunday, our Men thought they could not serve God Better then to require Justice of the Indians for the Innocent Blood which had been so oft by those Truc[ul]ent Savages shed; and we were cheerfully ready (as so many Sampsons) to forgo our own lives to be revenged of these Philistines, that had made Sport with our miseries; we marched through the Snow and came to a thick Swamp... wherein were encamped 3500 Indians. We first demanded to have Philip and his Adherents to be delivered Prisoners to us, according to Articles: And had no other Answer but shot; then we fired about 500 Wigwams... and killed all that we met with of them, as well Squaws and Papooses, (i.e. Women and Children) as Sanups (i.e Men.). In the midst of the wood was a plain piece of Ground on which the Indians had built a Fort…

We were no sooner entered the fort, but our enemies began to fly; and ours had now a carnage rather than a fight, for everyone had their fill of blood. It did greatly rejoice our men to see their enemies, who had formerly skulked behind shrubs and trees, now to be engaged in a fair field, where they had no defence but in their arms, or rather their heels. But our chiefest joy was to see they were mortal, as hoping their death will revive our tranquillity, and once more restore us to a settled peace…

This fight and execution continued from three o’clock in the afternoon till night, and then we left the flying enemy to take care of our wounded, and to carry off our dead.

We have slain of the enemy about 500 fighting men, besides some that were burnt in their wigwams, and women and children the number of which we took no account of…

The Great Swamp Fight shattered Narragansett power, but it also radicalised the conflict. Survivors joined Metacom’s forces, intensifying raids in 1676. For the English colonists, the battle became a foundational story of sacrifice and providential victory; for Native communities, it is remembered as a massacre. The site is now marked by a monument.

Planning to get away with it, 1956

Dr John Bodkin Adams was an Irish-born GP practising in Eastbourne on the English south coast. By the mid-1950s, local officials and some colleagues had become suspicious about the high number of deaths among his wealthy, often elderly patients – and the fact that many left him legacies in their wills.

After a lengthy, discreet investigation, the police first arrested him in November 1956 on charges relating to forged prescriptions and cremation forms. On 19 December 1956, they arrested him again and formally charged him with the murder of one of his patients, Edith Morrell, who had died in 1950 after heavy sedation with heroin and morphine.

When told of the murder charge on 19 December, Adams reportedly responded with a remark that would haunt all later discussions of the case:

Murder? Murder? Can you prove it was murder? I did not think you could prove it was murder. She was dying in any event.

This statement is recorded in contemporary police notes and quoted in several later accounts, including the newspapers the next day, reporting on a “17-minute hearing in a crowded but hushed court” (London Evening News). As he was taken away, Adams (“balding and heavily built”) allegedly “walked into the hall of his house and, grasping the hand of his receptionist, said, ‘I will see you in Heaven.’”

Adams’s 1957 trial for the murder of Edith Morrell became one of the most sensational British criminal trials of the 20th century, raising troubling questions about end-of-life care, intent and medical privilege. During the trial, Adams commented: “Easing the passing of a dying person isn’t all that wicked. She wanted to die. That can’t be murder. It is impossible to accuse a doctor.” He was acquitted of murder, and later charges were quietly dropped, but he was convicted of lesser offences (including prescription fraud).

Despite being struck off the Medical Register, Adams continued to help his loyal (surviving) patients, and was even reinstated in 1961. He died in 1983.

The case influenced debates about assisted dying and palliative care for decades afterwards. His remark on 19 December – “She was dying in any event” – crystallised anxieties about whether doctors might, deliberately or otherwise, hasten death under the guise of relieving suffering, and what the law should say about it. And inevitable parallels were drawn years later, in 2000, when Dr Harold Shipman was found guilty of murdering 15 patients (he was suspected of as many as 250), the first doctor to be successfully prosecuted for this crime. So it goes.

There must come a point where the pain of cancer is treated with painkillers so strong that they kill the patient. I certainly don't envy the doctor that has to make that borderline decision.