The French invade Wales, 1797

Just why was Jemima so great…?

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe!)

The veil of night was kindly drawn over their execrable orgies, disgraceful to nature, and which humanity shudders to imagine…

Erudite historians are fond of pointing out that the last time Britain was invaded (assuming you overlook the airborne Battle of Britain of 1940) was not 1066, but in fact 1797, in the Battle of Fishguard. I’m not going to tell the whole story here, but in brief, around 1,400 Frenchmen (many of them convicts) and Irishmen, led by the American William Tate, landed at Carregwastad Point near Fishguard on 22 February, and an assortment of them rampaged around northern Pembrokeshire in a drunken haze – partly thanks to booze stored at a farm for an upcoming wedding. The Fishguard Fencibles, led by Lt Col Thomas Knox, had to retreat in the face of the greater French forces – but ultimately Tate was tricked by Pembrokeshire grandee Lord Cawdor, commander of the Pembrokeshire Yeomanry, into thinking the British defences (a few hundred men and some angry locals armed with whatever they could lay their hands on) were larger and then surrendered. Numerous books have been written about the events, which have a rather comical tinge – although at the time the events were serious enough to cause a run on the Bank of England.

There are many accounts of the events, often contradictory, spurious or written long after the event. Here (with some modernised spellings) is an extract from what historians have found to be one of the most reliable, A Brief Narrative of the French Invasion near Fishguard Bay, by the topographer James Baker, and written in 1797:

On Wednesday, February 22, about two o’clock P. M. a day more than ordinarily mild and serene for the season of the year… the inhabitants of the parish of Llanwnda, which forms one side of Fishguard Bay, had their attention excited by the sudden appearance of a squadron of ships, consisting of two large frigates, a corvette and a lugger, in the channel, and fast nearing their shores; … there was no mistaking an invading foe; and thus every other passion became swallowed up in fear…

The principal witnesses to the enemy’s first manoeuvres, and to much of their subsequent conduct, were John Owen and John Davey, mariners, the crew of a small coasting sloop, laden with culm, who had been boarded by one of the French reconnoitring boats and carried prisoners to the Commodore’s ship, on board of which was also the General commanding the troops on this expedition. The use here made of the captives, was to learn from them the state of the harbour and port of Fishguard…

[The invaders] fell upon an expedient in setting fire to the furze and heath which every where clothed the summits of the cliffs, and which by a long run of dry weather was become very combustible ; by that means the darkness was considerably subdued, and security was given to their hazardous footing, notwithstanding they lost some lives, whilst much of their ammunition and some bread was dashed to pieces and lost among the rocks and breaking waves. This latter expedient, so favourable to the invaders, was to the alarmed and scattered inhabitants a signal for the most extreme distress; for … no less could be conceived but that their houses and haggards were involved in the conflagration.

Baker goes on to describe Knox’s advance and retreats, and the eventual surrender of the invaders.

An enduring story from this invasion is that a number of local women marched up and down in Welsh dress – noted for its red flannel cloaks and tall hats, vaguely reminiscent of redcoat army uniforms – in order to create the impression from a distance of greater defensive forces. Baker doesn’t mention this, and nor does local historian Richard Fenton, living in the area at the time and who wrote briefly of the invasion in his 1810 book A Historical Tour through Pembrokeshire. He comments even then on the variety of stories: “the accounts which have been given of it to the public are as various as the passions of the different narrators, now magnified beyond the bounds of probability”. (A load of red flannel, anyone?) And he certainly doesn’t stint on the depredations of the invaders: “the veil of night was kindly drawn over their execrable orgies, disgraceful to nature, and which humanity shudders to imagine”.

But there are a small number of contemporary sources for this tale. For example:

A letter from John and Mary Mathias of Narberth to their sister, written on 27 February: “The country gathered from all parts of Pembrokeshire near four hundred women in red flannel and Squire Cambel [Lord Cawdor] went to ask them were they to fight and they said they were.”

Another letter, from a John Mends of Haverfordwest to his son on the same day, refers to “poor women with red flannel over their shoulders, which the French at a distance took for soldiers, as they appeared all red”.

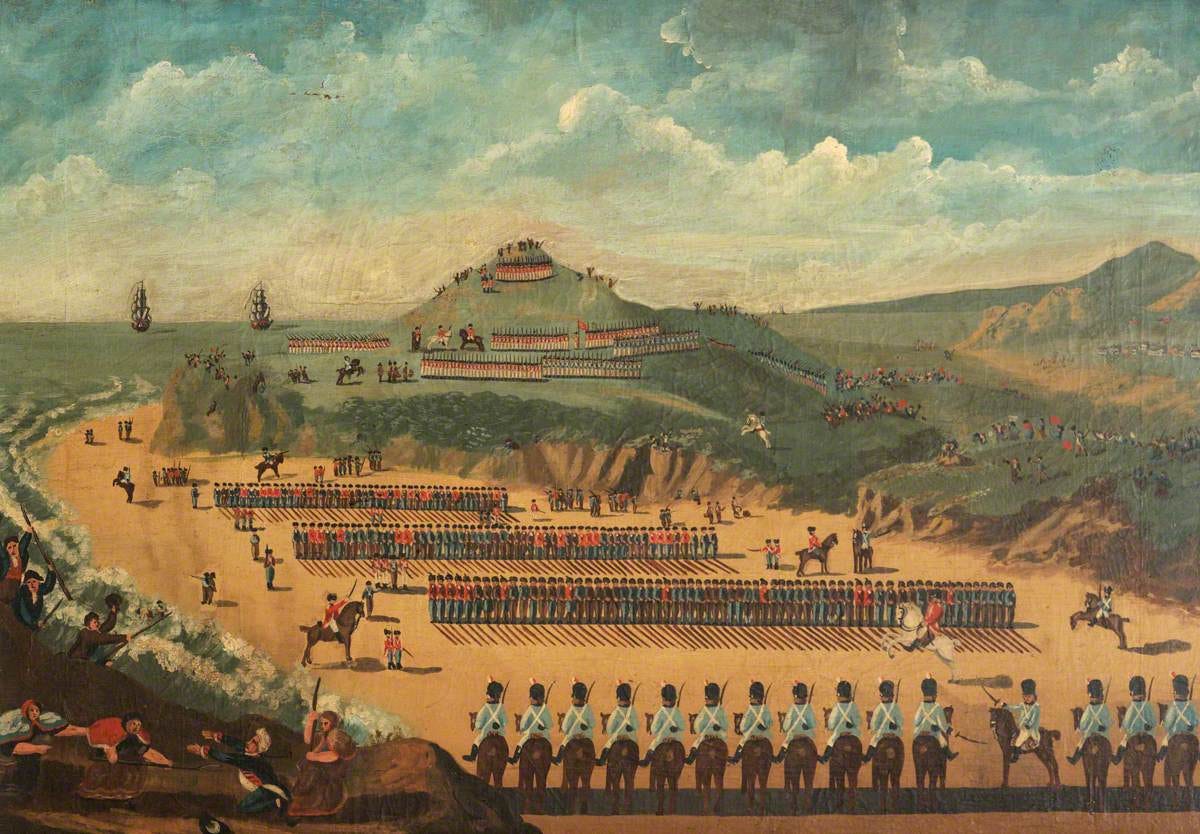

The painting above (presumed to be fairly contemporary) shows local women on the hillside, though more blue than red perhaps. The letters above suggest there must be something to the tale. Interestingly, there’s a similar story from Devon, when the invaders first approached the coast there; and from the English Civil War when Royalists approached Lyme Regis by sea in 1644, and local women apparently wore red hats and cloaks to make the defenders appear more numerous. Is this is a case of a myth that reappears, or a genuine, pragmatic defensive strategy used by local people down the ages..?

One more legend from the Battle of Fishguard before I go: that of one Jemima Nicholas, who supposedly encouraged the women in their defensive measures, and allegedly captured as many as 12 French soldiers and locked them in St Mary’s church.

But did she even exist..? Certainly a Jemima Nicholas who died in 1832, aged 82, is commemorated with a gravestone at St Mary’s, which praises ‘the Welsh heroine who boldly marched to meet the French invaders’ – but this was erected for the centenary in 1897. She is given pride of place in the Last Invasion Tapestry. But clear proof of her life and deeds has been hard to find.

In 2006, a family historian found a baptism record from 1755, ‘only’ six years out for matching the dates on the gravestone. Others have claimed descent from her. And when she died in 1832, the local vicar, Samuel Fenton – son of the Richard above – wrote in the parish register:

This woman was called Jemima Fawr or Jemima the Great from her heroine acts, she having marched against the French who landed hereabout in 1797 and being of such personal powers as to be able to overcome most men in a fight. I recollect her well. She followed the trade of a shoemaker and made me, when a little boy, several pairs of shoes.

Local man Syd Walters, in his 1992 A Truthful History of the Last Invasion of Britain, won’t have it: he insists the whole thing was made up by Samuel Fenton himself.

The first written account of Jemima’s deeds appears to be H.L. Williams’ An Authentic Account of the Invasion by French Troops, written long after the events, in 1842 – but he had been one of the Fishguard Fencibles at the time. He wrote:

Jemima Nicholas, an inhabitant of the town of Fishguard, a tall stout, masculine female, who worked as a shoemaker and cobbler, felt imbued with the noble and patriotic spirit of Ancient Cambria – she took a pitchfork and boldly marched to Pencaer… On her approach she saw, in a field, about twelve Frenchmen, not a whit daunted she advanced to them and whether alarmed at her courage, or persuaded by her rhetoric, she had the address to conduct them to, and confine them in the guard- house, in Fishguard church.

Another local antiquarian, the Rev Henry Vincent (1799–1865), although born after the invasion, did know Jemima. He wrote that she was “altogether the most muscular [woman] my eyes ever beheld” – and he hinted that she liked to tell tall tales when “she was rewarded by the inhabitants with as much ale as she could drink, and that not a little”. Was Jemima Fawr (where Fawr/Vawr is Welsh for ‘big’) great of deeds – or just great of stature? I’ll leave you to decide for yourself!

Of course, but they gave the thumbs-down to New South Wales, so I suspect Fishguard just put them off Wales in toto.

Is it not possible, even likely, that the French, having had a chance to look around North Wales, said "Pah! Cela n'en vaut pas la peine!" as they did with Australia!