Murder will out, 1692

When the king ordered 'burn their houses, seize or destroy their goods'…

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe!)

They had been all received as Friends by those poor People, who intending no Evil themselves, little suspected that their Guests were designed to be their Murderers.

After last week’s light-hearted historical mishap, something more serious this time, I’m afraid. Tomorrow (13 February) marks the anniversary of the Massacre of Glencoe in 1692. This forlorn event was one of many in the long struggle between the Jacobites of Scotland – supporters of the House of Stuart’s claim to the British throne (to some degree Catholics, though many were actually Protestant) – and the new monarchy of William of Orange and his wife Mary, who had jointly taken the throne only three years earlier.

In that same year, 1689, the Jacobites had risen up and defeated the new rulers at Killiecrankie, but their strength was gradually eroded after losses in further battles at Dunkeld and Cromdale. In 1690, the Secretary of State, Lord Stair, offered the Jacobite clan leaders £12,000 for swearing allegiance to William and Mary. Some of those leaders were late for the deadline (1 January 1692), or reluctant to take the oath, holding out for a possible return by James II.

One of them was Alasdair MacIain, head of a branch of the Clan MacDonald. He left his seat in Glencoe on 30 December to take the oath from Lieutenant Colonel John Hill, governor of Inverlochy (later Fort William). Hill declined to administer the oath, but gave MacIain a letter to take to the Sheriff of Argyllshire, whom MacIain visited on 6 January. Alas this slight delay was seized upon by the government and used to make an example. The mild-mannered Hill was apparently bypassed and a letter sent to his second-in-command, James Hamilton, who was ordered to take 400 men and block the exits from the Glencoe valley, while Major Robert Duncanson would sweep up from the south, kill the inhabitants and destroy their property.

Documents of the period make it clear that the government was already planning something this kind anyway. On 2 December, Lord Stair had written: “God knows whether the 12,000 l. sterling had been better employed to settle the Highlands, or to ravage them…”; and on 11 January he wrote, “it’s a great work of charity to be exact in rooting out that damnable sect” [the MacDonalds]. More starkly still, William III wrote on the same day: “You are hereby ordered and authorized to march our troops… and to act against these Highland rebels who have not taken the benefit of our indemnity, by fire and sword, and all manner of hostility; to burn their houses, seize or destroy their goods or cattle…”

In the violence that ensued on 13 February, dozens of people were killed (figures vary, but it seems to have been at least 30), MacIain among them, and others probably died later of exposure. Hill and Hamilton were later cleared of a charge of murder, and in fact the whole event was covered up, only coming to light when documents were accidentally left in an Edinburgh coffee house. The Jacobite cause flared and flamed on, of course, until its symbolic defeat at Culloden in 1746 (by which time Glencoe itself had been largely abandoned) – although they have their supporters to this day.

There don’t appear to be any immediate first-hand accounts of the massacre itself, but there are contemporary documents which give a pretty good indication of events – below are a few (with edited spelling). Some of this material can be found in the excellent anthology Scotland: An Autobiography.

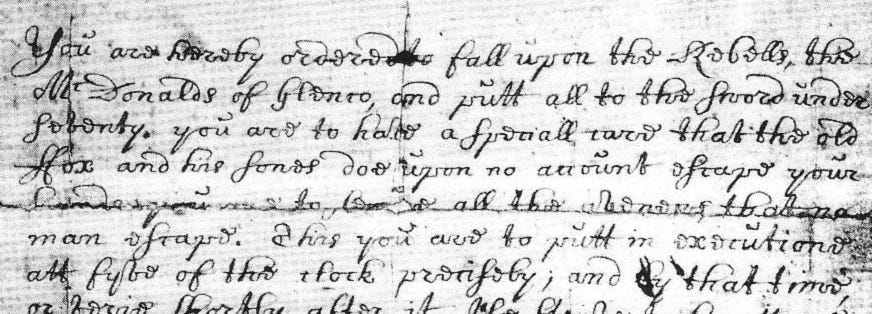

On the day before, Duncanson gave this order to Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon (whose own lands had purportedly been looted by MacIain three years earlier):

You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebels, the McDonalds of Glencoe, and put all to the sword under seventy. You are to have a special care that the old Fox and his sons do upon no account escape your hands, you are to secure all the avenues that no man escape. This you are to put in execution at five of the clock precisely; and by that time, or very shortly after it, I’ll strive to be at you with a stronger party: if I do not come to you at five, you are not to tarry for me, but to fall on. This is by the King’s special command, for the good & safety of the Country, that these miscreants be cut off root and branch. See that this be put in execution without feud or favour, else you may expect to be dealt with as one not true to King nor Government, nor a man fit to carry Commission in the Kings service.

The day after, John Hill himself wrote:

…I have also ruined Glencoe. Old Glencoe [i.e. MacIain] and Achtriaton being killed with 36 more, the rest by reason of an extraordinary storm escaped, but their goods are a prey to the soldiers and their houses to the fire, who may get other broken men to join them and be very troublesome to the country… I hope this example of justice and severity upon Glencoe will be enough.

The closest document we have to an account of what actually happened is in a letter published in Edinburgh on 20 April, only weeks after the events. It was originally entitled ‘A Letter from a Gentleman in Scotland, to his Friend at London, who desired a particular Account of the Business of Glenco’, but later circulated in a pamphlet in 1695, attacking William III and entitled Gallienus Redivivus, or Murther Will Out. The author is believed to be Charles Leslie (1650–1722), an Irish supporter of the Jacobites.

Gallienus Redivivus, or Murther will out

… The soldiers being disposed five or three in a House, according to the number of the Family they were to assassinate, had their orders given them secretly. They had been all received as Friends by those poor People, who intending no Evil themselves, little suspected that their Guests were designed to be their Murderers. At 5 o’clock in the Morning they began their bloody Work, surprised and butchered 38 persons, who had kindly received them under their Roofs. MacIain himself was murdered, and is much bemoaned; he was a stately well-favoured Man, and of good Courage and Sense…

I cannot without horror represent how that a Boy about Eight Years of Age was murdered; he seeing what was done to others in the House with him, in a terrible Fright ran [out] of the House, and espying Capt Campbell, grasped him about the Legs, crying for Mercy, and offering to be his Servant all his Life. I am informed Capt Campbell inclined to spare him, but one Drummond, an Officer, barbarously ran his Dagger through him, whereof he died immediately. The rehearsal of several Particulars and Circumstances of this tragical Story, makes it appear most doleful; as that MacIain was killed as he was drawing on his Breeches, standing before his Bed and giving orders to his Servants for the good Entertainment of those who murdered him; while he was speaking the words, he was shot through the Head, and fell dead in his Lady’s Arms, who through the grief of this, and other bad Usages she met with, died the next day.

It is not to be omitted, that most of those poor People were killed when they were asleep, and none was allowed to pray to God for Mercy. Providence ordered it so, that that Night was most boisterous; so as a Party of 400 Men, who should have come to the other end of the Glen, and begun the like Work there at the same hour, (intending that the poor Inhabitants should be enclosed, and none of them escape) could not march that length, until it was Nine o’Clock, and this afforded to many an opportunity of escaping, and none were killed but those in whose Houses Campbell of Glenlyon’s Men were Quartered, otherwise all the Male under 70 Years of Age, to the number of 200, had been cut off, for that was the order; and it might have easily been executed, especially considering that the Inhabitants had no Arms at that time; for upon the first hearing that the Soldiers were coming to the Glen, they had conveyed them all out of the way: For though they relied on the Promises which were made them for their Safety; yet they thought it not improbable that they might be disarmed. I know not whether to impute it to difficulty of distinguishing the difference of a few Years, or to the Fury of the Soldiers, who being once glutted with Blood, stand at nothing, that even some above Seventy Years of Age were destroyed. They set all the Houses on Fire, drove off all the Cattle to the Garrison of Inverlochy, viz. 900 Cows, 200 Horses, and a great many Sheep and Goats, and there they were divided among the Officers. And how dismal may you imagine the Case of the poor Women and Children was then! It was lamentable, past expression; their Husbands and Fathers, and nearest Relations were forced to flee for their Lives; they themselves almost stripped, and nothing left them, and their Houses being burnt, and not one House nearer than six Miles, and to get thither they were to pass over Mountains, and Wreaths of Snow, in a vehement Storm, wherein the greatest part of them perished through Hunger and Cold. It fills me with horror to think of poor stripped Children, and Women, some with Child, and some giving Suck, wrestling against a Storm in Mountains, and heaps of Snow, and at length to be overcome, and give over, and fall down, and die miserably.