Pioneers of dieting, 1863

What are 'human beans'?

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe!)

I have tried sea air and bathing in various localities, with much walking exercise; taken gallons of physic…; riding on horseback; the waters and climate of Leamington many times, as well as those of Cheltenham and Harrogate frequently; have lived upon sixpence a-day…; and have spared no trouble nor expense in consultations with the best authorities in the land, giving each and all a fair time for experiment, without any permanent remedy

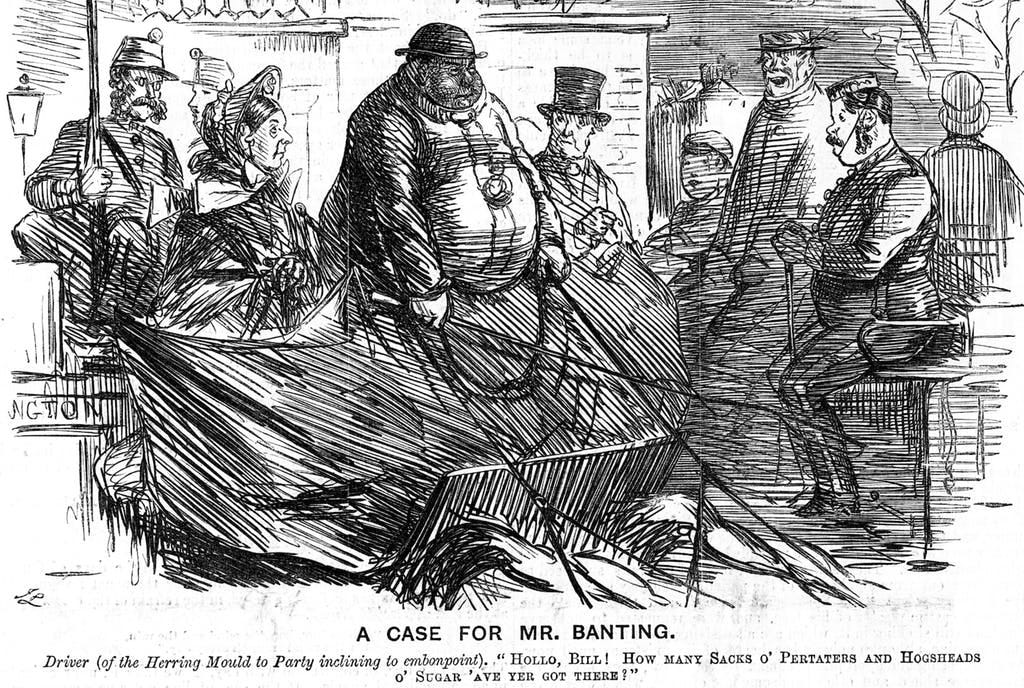

January is of course the time of year when many people start a new diet or some other plan for self-improvement. Dieting as we know it is not a new phenomenon, as Jayne Shrimpton reveals in her history of this activity in this month’s edition of Discover Your Ancestors. A pioneer, whose personal weight-loss success led to what we might think of as the first dieting fad (which is not to undermine his success), was William Banting (1797–1878), an undertaker to the nobility who was plagued by weight problems.

He tried many things to no avail, until he happened to consult an ear surgeon named William Harvey in Soho Square, London over his hearing problems. Harvey had an insight that corpulence and diet were closely related (and in Banting’s case that his deafness came from a build-up of fat). In Harvey’s own words:

When in Paris, in the year 1856, I took the opportunity of attending a discussion on the views of M. Bernard [the French physiologist Claude Bernard, who made the connection between glucose and fat in the liver] … [It] occurred to me that excessive obesity might be allied to diabetes as to its cause, although widely diverse in its development: and that if a purely animal diet were useful in the latter disease, a combination of animal food with such vegetable matters as contained neither sugar nor starch, might serve to arrest the undue formation of fat.

Inspired by Harvey’s advice, Banting found great success in losing weight, and was moved to write ‘A Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public’ in 1863, detailing the approach he took. This is, of course, essentially a low-carb diet and Harvey should perhaps be given the ultimate credit for the modern versions such as the Atkins diet.

Banting’s letter explaining this method became so successful that it went through multiple editions, selling 50,000 copies, and he became a household name, such that ‘to bant’ meant ‘to diet’. Here’s a snippet from a popular song of the time:

If you don’t follow Banting,

You won’t much longer get about,

If you continue thus so stout,

You’ll fall a victim to the gout,

You really must try Banting.

Here is an extract from Banting’s charming and heartfelt ‘Letter’:

Of all the parasites that affect humanity I do not know of, nor can I imagine, any more distressing than that of Obesity, and, having just emerged from a very long probation in this affliction, I am desirous of circulating my humble knowledge and experience for the benefit of my fellow man, with an earnest hope it may lead to the same comfort and happiness I now feel under the extraordinary change,—which might almost be termed miraculous had it not been accomplished by the most simple common-sense means…

I am now nearly 66 years of age, about 5 feet 5 inches in stature, and, in August last (1862), weighed 202 lbs., which I think it right to name… I now weigh 167 lbs., showing a diminution of something like 1 lb. per week since August, and having now very nearly attained the happy medium, I have perfect confidence that a few more weeks will fully accomplish the object for which I have laboured for the last thirty years, in vain, until it pleased Almighty Providence to direct me into the right and proper channel—the “tramway,” so to speak—of happy, comfortable existence.

Few men have led a more active life—bodily or mentally—from a constitutional anxiety for regularity, precision, and order, during fifty years’ business career, from which I have now retired, so that my corpulence and subsequent obesity was not through neglect of necessary bodily activity, nor from excessive eating, drinking, or self-indulgence of any kind, except that I partook of the simple aliments of bread, milk, butter, beer, sugar, and potatoes more freely than my aged nature required, and hence, as I believe, the generation of the parasite, detrimental to comfort if not really to health.

… I consulted high orthodox authorities (never any inferior adviser), but all in vain. I have tried sea air and bathing in various localities, with much walking exercise; taken gallons of physic and liquor potassæ, advisedly and abundantly; riding on horseback; the waters and climate of Leamington many times, as well as those of Cheltenham and Harrogate frequently; have lived upon sixpence a-day, so to speak, and earned it, if bodily labour may be so construed; and have spared no trouble nor expense in consultations with the best authorities in the land, giving each and all a fair time for experiment, without any permanent remedy… the evil still increased, and, like the parasite of barnacles on a ship, if it did not destroy the structure, it obstructed its fair, comfortable progress in the path of life.

I have been in dock, perhaps twenty times in as many years, for the reduction of this disease, and with little good effect—none lasting. Any one so afflicted is often subject to public remark, and though in conscience he may care little about it, I am confident no man labouring under obesity can be quite insensible to the sneers and remarks of the cruel and injudicious in public assemblies, public vehicles, or the ordinary street traffic; … therefore he naturally keeps away as much as possible from places where he is likely to be made the object of the taunts and remarks of others.

Although no very great size or weight, still I could not stoop to tie my shoe, so to speak, nor attend to the little offices humanity requires without considerable pain and difficulty, which only the corpulent can understand…

At this juncture (about three years back) Turkish baths became the fashion, and I was advised to adopt them as a remedy. With the first few I found immense benefit in power and elasticity for walking exercise; so, believing I had found the “philosopher’s stone,” pursued them three times a-week till I had taken fifty, then less frequently (as I began to fancy, with some reason, that so many weakened my constitution) till I had taken ninety, but never succeeded in losing more than 6 lbs. weight during the whole course, and I gave up the plan as worthless; though I have full belief in their cleansing properties, and their value in colds, rheumatism, and many other ailments.

[Banting then explains how he met Harvey and the advice he was given.]

… happily, I found the right man, who unhesitatingly said he believed my ailments were caused principally by corpulence, and prescribed a certain diet,—no medicine, beyond a morning cordial as a corrective,—with immense effect and advantage both to my hearing and the decrease of my corpulency.

For the sake of argument and illustration I will presume that certain articles of ordinary diet, however beneficial in youth, are prejudicial in advanced life, like beans to a horse, whose common ordinary food is hay and corn. It may be useful food occasionally, under peculiar circumstances, but detrimental as a constancy. I will, therefore, adopt the analogy, and call such food human beans. The items from which I was advised to abstain as much as possible were:—Bread, butter, milk, sugar, beer, and potatoes, which had been the main (and, I thought, innocent) elements of my existence, or at all events they had for many years been adopted freely.

These, said my excellent adviser, contain starch and saccharine matter, tending to create fat, and should be avoided altogether. At the first blush it seemed to me that I had little left to live upon, but my kind friend soon showed me there was ample, and I was only too happy to give the plan a fair trial, and, within a very few days, found immense benefit from it. It may better elucidate the dietary plan if I describe generally what I have sanction to take, and that man must be an extraordinary person who would desire a better table:—

For breakfast, I take four or five ounces of beef, mutton, kidneys, broiled fish, bacon, or cold meat of any kind except pork; a large cup of tea (without milk or sugar), a little biscuit, or one ounce of dry toast.

For dinner, Five or six ounces of any fish except salmon, any meat except pork, any vegetable except potato, one ounce of dry toast, fruit out of a pudding, any kind of poultry or game, and two or three glasses of good claret, sherry, or Madeira — Champagne, Port and Beer forbidden.

For tea, Two or three ounces of fruit, a rusk or two, and a cup of tea without milk or sugar.

For supper, Three or four ounces of meat or fish, similar to dinner, with a glass or two of claret.

For nightcap, if required, A tumbler of grog—(gin, whisky, or brandy, without sugar)—or a glass or two of claret or sherry.

This plan leads to an excellent night’s rest, with from six to eight hours’ sound sleep. The dry toast or rusk may have a table spoonful of spirit to soften it, which will prove acceptable. Perhaps I did not wholly escape starchy or saccharine matter, but scrupulously avoided those beans, such as milk, sugar, beer, butter, &c., which were known to contain them.

On rising in the morning I take a table spoonful of a special corrective cordial, which may be called the Balm of life, in a wine-glass of water, a most grateful draught, as it seems to carry away all the dregs left in the stomach after digestion, but is not aperient; then I take about 5 or 6 ounces solid and 8 of liquid for breakfast; 8 ounces of solid and 8 of liquid for dinner; 3 ounces of solid and 8 of liquid for tea; 4 ounces of solid and 6 of liquid for supper, and the grog afterwards, if I please. I am not, however, strictly limited to any quantity at either meal, so that the nature of the food is rigidly adhered to.

Experience has taught me to believe that these human beans are the most insidious enemies man, with a tendency to corpulence in advanced life, can possess, though eminently friendly to youth. He may very prudently mount guard against such an enemy if he is not a fool to himself, and I fervently hope this truthful unvarnished tale may lead him to make a trial of my plan, which I sincerely recommend to public notice,—not with any ambitious motive, but in sincere good faith to help my fellow-creatures to obtain the marvellous blessings I have found within the short period of a few months. [It should be added that Banting gave the profits from his pamphlet to charity!]

I do not recommend every corpulent man to rush headlong into such a change of diet, (certainly not), but to act advisedly and after full consultation with a physician.

… [T]he result of my experience is briefly as follows:—

I have not felt so well as now for the last twenty years.

Have suffered no inconvenience whatever in the probational remedy.

Am reduced many inches in bulk, and 35 lbs. in weight in thirty-eight weeks.

Come down stairs forward naturally, with perfect ease.

Go up stairs and take ordinary exercise freely, without the slightest inconvenience.

Can perform every necessary office for myself.

The umbilical rupture is greatly ameliorated, and gives me no anxiety.

My sight is restored—my hearing improved.

My other bodily ailments are ameliorated; indeed, almost past into matter of history.

I have placed a thank-offering of £50 in the hands of my kind medical adviser for distribution amongst his favourite hospitals, after gladly paying his usual fees, and still remain under overwhelming obligations for his care and attention, which I can never hope to repay. Most thankful to Almighty Providence for mercies received, and determined to press the case into public notice as a token of gratitude…

WILLIAM BANTING, Sen.,

Late of No. 27, St. James’s Street, Piccadilly,

Now of No. 4, The Terrace, Kensington.

May, 1863.