(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe.)

He was pleasant of approach and cheerful of manner, opposed to quarrels and strife: a friend, at the same time, of all in the service with him who were men of honour and good life.

Remember, remember the fifth of November… We probably all know the bones of the story of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, when a group of Catholic conspirators attempted to blow up King James I in Parliament, the first of them to be caught being Guy Fawkes, who we remember in one incendiary way or another to this day.

The date set me wondering whether any of Mr Fawkes’s own words have come down through history. The answer is ‘yes and no’, and reflects one of the many challenges in looking for ‘first-hand’ sources from history. In essence, we have various contemporary reports of the man, some claiming to quote him, although the accuracy is hard to determine. But perhaps at least they give us glimpses of the real man who was caught with those barrels of gunpowder.

Guy Fawkes was born in York in 1570; his family were ostensibly worshippers in the still relatively new Church of England, although his mother’s family were Catholics; and after Guy’s father Edward died, she remarried the more overtly Catholic Denis Bainbridge. In the 1590s, young Guy went to fight for the Catholic side of Spain against the Dutch (part of the Eighty Years’ War).

By 1603, Guy was styling himself as Guido to sound more European, and went to the court of Philip III of Spain to garner support for a Catholic rebellion in England. And here’s where we have our first glimpse of him, through a document now in the state papers of Spain.1 It’s not written by him, but claims to quote his sentiments against James I, who was of course new to the throne of England, having sat previously on that of Scotland:

What the gentleman who came from England confided to me to report by word of mouth to his Majesty [i.e. Philip] is the following.

First he says that the king is a heretic and has demonstrated that he is one as it appears for on his journey through England he granted pardon to many wrongdoers and others then in prison for debt when he ordered them to be freed from their prisons, but not to any Catholic…

A Scottish Catholic peer told a Jesuit in Brussels that he heard on that journey the king tell his Scottish friends that he hoped in a short time to have all of the papist sect driven out of England.

Many have heard him say at table that the pope is Anti-Christ which he wished to prove to anyone who believed the opposite.

He allows himself to be ruled by Sir George Home, his favourite, who has always been one of the greatest heretics in all of Scotland.

Philip wasn’t willing to help, and Fawkes then fell in with the fledgling plot to kill James led by Robert Catesby – the five main plotters first met in a London pub, the Duck and Drake, on 20th May 1604. Fawkes’s role was to become the lighter of the fuse, before fleeing across the Thames and heading for France.

We do have a glowing description2 of Guy from a schoolfriend, Oswald Tesimond, who himself became a Jesuit priest in October 1603:

He was a man of considerable experience as well as knowledge. Thanks to his prowess he had acquired considerable fame and name among the soldiers. He was also something decidedly rare among soldiery, although it was immediately evident to all – a very devout man, of exemplary life and commendable reticence. He went often to the sacraments. He was pleasant of approach and cheerful of manner, opposed to quarrels and strife: a friend, at the same time, of all in the service with him who were men of honour and good life. In a word, he was man liked by everyone and loyal to his friends.

Fawkes, of course, never lit that fuse. Thanks to an anonymous tip-off sent to Lord Monteagle, the cellars were searched on the night of 4th/5th November, and he was caught. He gave his name as John Johnson, perhaps as an epitome of generic Englishness given his relatively exotic real name, and now we find him again in the records, in this case the Calendar of State Papers Domestic for the reign of James I.3 Here are the parts where he is referenced…

Nov. 5 [Tower]

First examination of Guy Faukes, under the assumed name of John Johnson. Particulars of his past life; served Thos. Percy; details of the intended Plot; refuses to reveal the names of the conspirators…

Examination of Gideon Gibbins, porter. He and 2 others carried 3,000 billets to the vaults under the Parliament House, which Johnson (Guy Faukes) piled up.

Nov. 6 [Tower]

Examination of John Johnson (Guy Faukes) as to the storing of powder, &c. in the Parliament cellar,—his connections abroad,—whether Mr. Percy would have allowed the Earl of Northumberland to perish, &c. He refuses to inculpate any person, saying, “youe would have me discover my frendes: the giving warning to one overthrew us all;” signed “John Johnson.”

Nov. 7 [Tower]

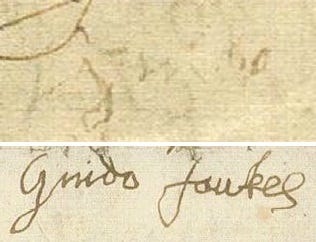

Examination of Guy Faukes. The conspiracy began eighteen months before; was confined to five persons at first, then to two; and afterwards five more were added, who all swore secrecy; he refuses, on account of his oath, to accuse any; they intended to place the Princess Elizabeth on the throne, and marry her to an English Catholic. Signed at the foot of each page “Guido Faukes.” [See below.]

… Information, that Faukes lodged two months ago, with Mrs. Herbert, now Mrs. Woodhouse, at the back of St. Clement’s church. Percy, the two Wrights, Winter, Catesby, and others had secret correspondence with him there. She disliked it, suspecting him to be a priest; he was tall, with brown hair and auburn beard, and had plenty of money.

Nov. 8 [Tower]

Sir Wm. Waad [Sir William Wade (1546–1623) was Lieutenant of the Tower of London] to Salisbury. Faukes is in a “most stubborn and perverse humour, as dogged as if he were possessed.” He promised to give a full account of the Plot, but now refuses…

Interrogatories [by Sir Edward Coke, the government’s prosecuting counsel], for the further examination of Guy Faukes, founded upon his deposition of Nov. 7. Indorsed with other queries relating to the Plot;—what foreign aid was expected; what were the designs of the conspirators as to the Princess Mary, whom, as English born, they intended to make Queen…

Deposition of Guy Faukes. Thos. Winter first proposed a conspiracy to him; Catesby, Percy, and John Wright were next taken into the scheme, then Chris. Wright, afterwards Sir Everard Digby, Amb. Rokewood, Francis Tresham, John Grant, Rob. Keyes, and many others. Details of the Plot, the same as in the examinations…

Names of the first five conspirators, and of seven more afterwards admitted; taken from the above examination of Faukes, by Levinus Munck. [An MP and Salisbury’s secretary.]

Nov. 9 [Tower]

Sir Wm. Waad to Salisbury [Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury and main discoverer of the plot]. Has persuaded Faukes to disclose “all the secrets of his heart” to his Lordship only, “but not to be set down in writing.” Undertakes to procure his acknowledgment and signature to his confession, by degrees. Advises Salisbury to speak with him alone.

Declaration of Guy Faukes [made to Salisbury]. Further details of the Plot. It was communicated to Hugh Owen, the Jesuit, in Flanders. The conspirators met at the back of St. Clement’s Inn… (On the 10th, this declaration was acknowledged before the Lords Commissioners, and is signed in a tremulous hand “Guido.” The signature is supposed to have been extorted by the rack, and the prisoner to have fainted before completing it.)

That “tremulous hand” is heartbreaking testament to Fawkes’s torture on the rack. King James himself (who was allegedly impressed by Fawkes’s “Roman resolution”) had issued this instruction: “The gentler tortours are to be first usid unto him, et sic per gradus ad ima tenditur, and so God speede youre goode worke.” (The Latin means “and so by degrees proceeding to the deepest”.) A note in the State Papers from December adds:

Faukes confessed nothing the first racking, but did so when told “he must come to it againe and againe, from daye to daye, till he should have delivered his whole knowledge.”

Guy Fawkes was executed on 31st January 1606, and if you want the gory details, by all means look them up for yourself.

The state records do give more extensive details of his declarations and confessions, and other 17th century documents – such as ‘A True Copy of the Declaration of Guido Fawkes’ in the King’s Book, which allegedly gives James’s own speech about the plot – elaborate on their text.4 One of the documents signed by Fawkes can be seen at The National Archives website, along with the transcription. I’m sure the substance of it is what Guy revealed about the stages and personnel of the conspiracy – but should we regard a third-person account extracted under torture as his own words? I’d rather not.

It was tracked down by Albert J. Loomie and published in 1971 as an appendix to his Guy Fawkes in Spain.

This was originally written in Italian, in Tesimond’s own account of the Gunpowder Plot.