[History by Numbers] The dating game

It's Julius vs Gregory…

A few years ago I read a fascinating article by Peter Maggs entitled ‘Confusion and myth in the Gregorian calendar reform’. I urge you to read it, although I will mention a few of its salient points here, as well as looking at the implications of calendar reform in general for family historians in particular.

The traditional Julian calendar, named after its proponent Julius Caesar, was adopted by the Romans, and therefore across Europe, in 45BC. It’s not as unfamiliar as one might imagine – in fact, the 12 months’ lengths were exactly the same as we use today. The main innovation of Julian reform was to add a leap day to February every four years.

However, this was not enough to stop a gradual drift between the human-imposed calendar and the wilful ways of nature: the Julian calendar ends up being slightly too long for the solar year, to the tune of one day every 128 years. As the centuries roll by, these things start to matter, with the calendar adrift from important events such as the equinoxes and solstices.

The Gregorian calendar (named after Pope Gregory XIII) proposed a fairly simple adjustment to this, namely that years evenly divisible by 100 are not leap years – unless they are evenly divisible by 400. So 1900 was not a leap year – but the millennial year of 2000 was (OK, let’s not get into the debate about the millennium actually being in 2001). This adjustment makes the average year length 365.2425 days, which is enough to mean the calendar only gains one day against the sun every 3030 years.

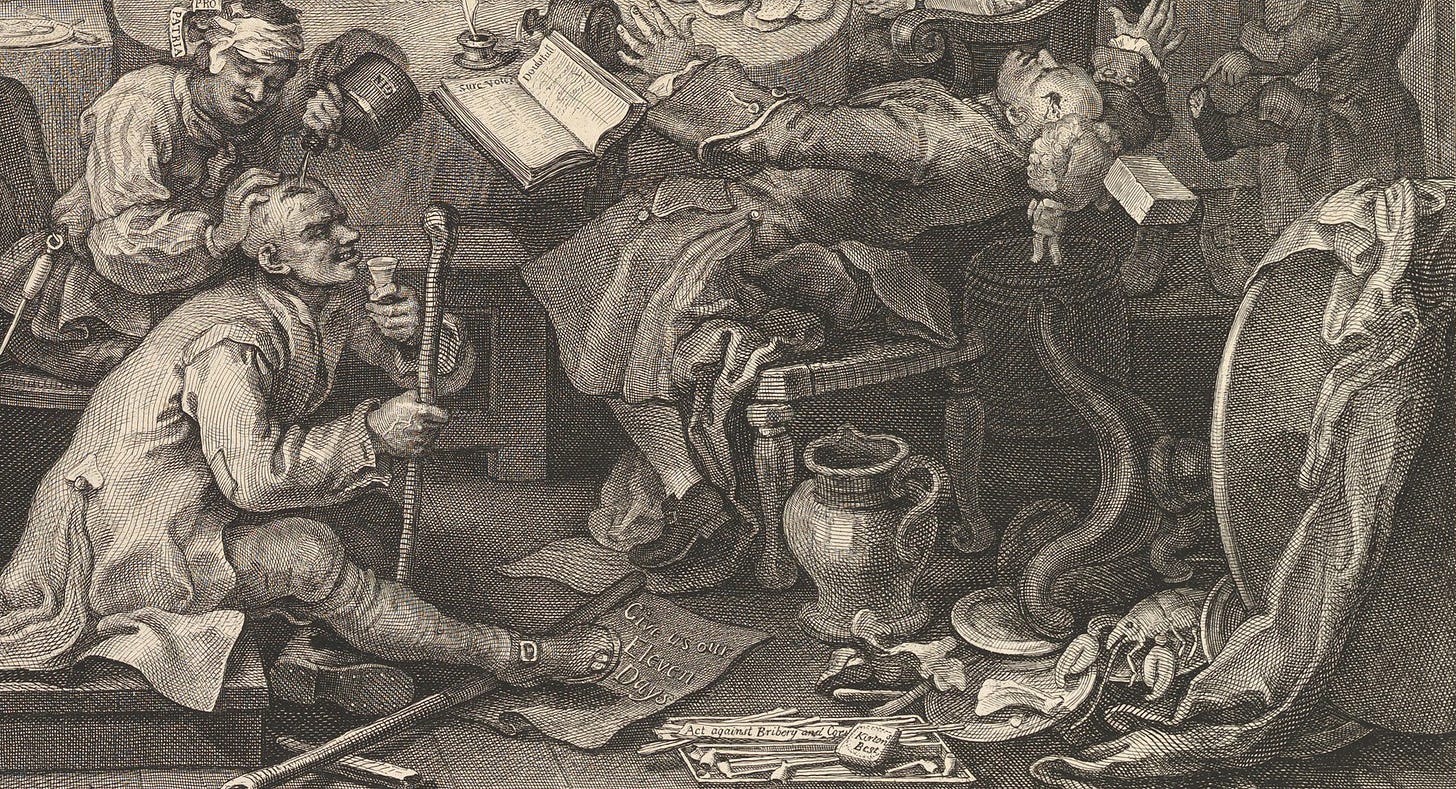

Calendar reform came late to Britain (and its colonies, including America).