An echo in her heart, 1686

Poverty and industry among the Huguenots

(Hello, this is Histories, a free weekly email exploring first-hand accounts from the corners of history… Do please share this with fellow history fans and subscribe.)

I should be infinitely happier working with my hands for daily bread with her, than living in wealth with any other woman on the face of the earth…

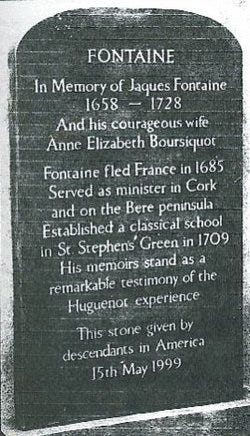

In last week’s Histories, we followed a group of Huguenots as they fled violent persecution in France, in search of a new life in England. Our eyewitness is Jaques de la Fontaine (1658–1728), later known as the Rev James Fontaine. His 1722 memoir gives a vivid account of their sufferings – and their joys. This week, some snapshots of both as he and his fiancée, Anne Boursiquot (1665–1721), forge a new life in south-west England, initially in Barnstaple, Devon.

Right away it becomes clear that Jaques – a Protestant minister – was an astute businessman, even if fortune did not always favour him, thanks to the unscrupulous people who sought to profit from the Huguenots’ desperation.

The first thing that struck me on my arrival in England was the extreme cheapness of bread. What with sea sickness and short provisions on board ship, we had suffered a good deal, and were well inclined to eat as soon as we landed. After returning thanks to God for our preservation, (of course our first act) we begged to have some bread, and they brought us very large biscuits, which in France would have cost two pence a piece, and to my surprise I was told their price was only a halfpenny… It instantly occurred to me, that if I had only some money at command to lay out in grain to send to France, I should realise a large profit. I knew that there were some French Refugees at Plymouth who had brought money with them, and I determined to borrow a horse and ride over there to suggest my plan to them…

Upon reflection I thought I might as well let mine host Mr. Downe have the benefit of my knowledge on this subject. He was very kind to me, therefore it seemed a duty to put him in the way of so advantageous a transaction. He entered into it very readily, the more so, from having been in trade in his youth…

Our whole property consisted of twenty gold pistoles, a silver watch, a gold chain, a pearl necklace, two diamonds, an emerald, and half a dozen silver spoons; and surely, to look at it in the most unfavourable light, these would be enough to cover any loss for which the Insurers were not responsible…

Mr. Downe chartered a vessel of about 50 tons, loaded her without delay, and consigned her to Mr. Boursiquot (your uncle,) and Peter Robin, a distant cousin of mine. You may guess their astonishment at receiving such a consignment from their relative, who had left his home so few weeks ago in poverty. Had the vessel arrived sooner, the adventure would have been more profitable, for the King had sent to foreign countries for grain, and his importation was all to be sold before the cargoes belonging to private individuals could be opened. Nevertheless, Peter Robin sold it for twice as much as it cost, and laid out the proceeds in the best wines of Bourdeaux and Langon, which also paid a profit…

We made still another adventure, and ordered the return cargo to be of salt; this was disastrous in the extreme. I lost more than I had gained and was saddled with debt besides. I will give the particulars. The Captain, after taking in his cargo, agreed to bring away some Protestants who had pretended to change their religion, in order to gain time to turn their property into cash to carry away with them. They unfortunately placed their money in the Captain’s hands for safe keeping, and he at once began to revolve in his mind how he could contrive to keep possession of the treasure. He decided upon going to Spain as the best plan… When between Bilboa and St. Sebastion, the wind and tide favouring their wicked designs they ran on the beach with every sail set, and the vessel was a complete wreck. Here was an end of my cargo of salt, it returned to the sea from whence it came.

The most horrible part of the story is yet to come, the Captain and crew went ashore in the boat with the money, leaving the passengers to be drowned, every wave going completely over the wreck; one of their number a lady of quality, who owned the largest part of the treasure, wore a quilted petticoat which buoyed her up so entirely that she might have floated ashore, had not the Captain seen her; he put off in his boat as though he would have assisted her, and when he got within reach he plunged her under water and held her down for a length of time, so that the petticoat, which had in the first instance resisted the water, becoming saturated prevented her rising…

My losses were so heavy that I was obliged to dispose of my watch, gold chain, and silver spoons, and still all was not paid…

[Jaques’ account now turns to a lighter matter, although money hovers in the background.]

I have already mentioned that I was hospitably received into the house of a Mr. Downe at Barnstaple; this gentleman was a bachelor of some forty years of age, and he had an unmarried sister living with him, who was about thirty three or thirty-four years old. They were kindness itself, and I was as completely domesticated with them as if I had been a brother. They were in very easy circumstances; the brother was worth £10,000 the sister £3,000. This poor lady unfortunately took a great fancy to me, and she persuaded herself that it would be an excellent thing for me to marry her and her brother to marry my intended. I should have imagined that she would have had no difficulty in persuading her brother to fall in love; for in those days your dear mother was very beautiful, her skin was delicately fair, she had a brilliant color in her cheeks, high forehead and a remarkably intellectual expression of countenance…

Miss Downe opened her project to me one day, by observing that she thought we must be two fools to think of marrying with no better prospect than beggary for our portion. I took no notice of what she said, but she persevered, and frequently gave me broad hints that I might do much better for myself. I was determined not to understand her, and our languages being different I was able to appear ignorant of her views, until one day her brother happened to enter the room when she was making an attack upon me, and she requested him to explain the matter to me… I should mention that Miss Downe’s personal appearance presented a strong contrast to that of her rival, she was short, thin, sallow and marked with the small-pox… By way of reply to this singular proposition I produced our written promise, solemnly signed by both of us; but I added that my love was so sincere that I could cheerfully resign my betrothed to a rich man, if she thought it would be for her happiness, and that I would engage to deliver the message to her with all possible fidelity.

I went that very evening to Mr. Fraine’s where she was staying, and executed the delicate commission with which I had been charged… As soon as she had heard what I had to say, she burst into tears, and was evidently under the impression that Miss Downe’s fortune had attracted me, and that I was anxious to break off our engagement. She gave me no answer but her tears, so I repeated the message, and assured her that the gallant was as much struck with her as the sister with me, and that she would have altogether the best of the bargain, because Mr. Downe’s property was more than three times as large as his sister’s. She then made an effort, and answered that I was free, she released me absolutely and entirely from every promise that I had ever made to her… and as to the future, she was contented to remain as she was, and wished to hear nothing more from Mr. Downe. I was completely overpowered by this, and my tears flowed as fast as hers. I then, with the utmost solemnity, asked her if she thought she could be contented to join me in working for our living… nevertheless if she was willing to run the risk, I should be infinitely happier working with my hands for daily bread with her, than living in wealth with any other woman on the face of the earth. She answered that every thing I said found an echo in her heart.

We were married on the 8th. Febr. 1686. at the Parish Church of Barnstaple. Mr. Fraine, at whose house my wife had lived from the day after our landing, prepared an excellent banquet and invited almost all the French Refugees in the neighbourhood to partake with us on our wedding day; and my friend Mr. Downe entertained us all in the same style on the following day.

Our funds were very low, for I had paid £5 for insurance, and £3 for the wedding ring and license, so that we could scarcely be much poorer than we were… The inhabitants of the town were generous in the extreme, they sent us all things essential for a small family, so that our house was furnished without costing us a farthing, and their liberality did not stop here; every market day meat, poultry, and grain came in abundance without our knowing to whom we were obliged, and during the six or eight months that we lived there, I only bought one bushel of wheat, and had two left when we removed.

[Jaques’ narrative continues with details of the various ways in which he tried to earn a living, and support his now growing family – their first child, James, was born in 1686, and seven others would follow. Jaques initially “accepted a situation in the family of Sir Halsewell Tynte, who lived two miles from Bridgwater” for £20 a year; then they tried and failed to run a shop in the same Somerset town. A fund existed to support the French refugees, but obliged them to “commune according to the rites of the Church of England”, which to Jaques “seemed to me to have too strong a resemblance to Popery”. He describes how circumstances forced him to go cap in hand…]

At one time, ground down by poverty, my spirit was so humbled that I went to London to make a personal application to the Committee, and my friends advised me to call upon certain Deans and other high dignitaries who were the most influential members of the Committee. My garments were old and shabby, and I found it difficult to gain an entrance to any of the great houses. The footman would leave me waiting a long time in the entry like a common beggar, and at last return to inform me that his Reverence was not then at leisure to see me. I would call again and again, till weary of opening the door, the servant, to avoid further importunity, would obtain for me the desired audience, and accompanying me through divers richly furnished apartments, watching carefully lest I should steal some of the plate that was piled up on the sideboards, introduce me to the apartment where the Dean was sitting. He enquired what I wanted with him, not even asking the poor beggar to take a seat…

All this was to no purpose so long as I was a Presbyterian. “He is a young man,” said they, “let him get a situation as a servant, his wife can do the same, and we will take care of his children in the house we have hired for the purpose.”

[He moved his family to Taunton, where their fortunes improved…]

I removed to Taunton for the purpose of teaching the French language, finding that I could obtain some pupils there. Our plan was to keep a shop also, and we were in great hopes that with both together we should be able to pay our way.

I borrowed £100 from a friend. I found the wholesale dealers in Bristol and Exeter very accommodating in the credits they granted me. As fast as I sold the goods I paid for them, and I was then allowed to take a fresh supply on credit…

About this time two Frenchmen called upon me whom I had known in great distress in Bridgwater, and I had there solicited charity for them, at the same time advising them to learn a trade so as to make themselves independent for the future; and I had suggested their binding themselves to some of the French manufacturers of light stuffs in Bristol, and assured them they would have to ask charity no more. They had taken my advice, and at the end of two years they visited me expressly to return their thanks. I did not recognise them; the rags and tatters in which they had formerly appeared had given place to decent and respectable clothing. They told me they were the persons whom I had recommended to learn a trade, that they had done so, and now all they wanted was a small advance from somebody, and they would work for half the profits. They urged me to undertake it, and they said £20 would suffice to buy worsted, yarn and dyes, and that they themselves had wherewithal to buy tools, and that if I would make the advance for them, they would work two years for me, and be contented with half the profit on the work… Behold me now not only a teacher of languages, and a shopkeeper, but a manufacturer also…

Every thing now seemed to prosper with me. I hired the handsomest shop in Taunton, opposite the cross in the Market place, and I was able to furnish it with so great a variety, that it was always filled with customers; and my wife and two boys to assist her, found ample employment.

And so we must leave them. The family eventually moved to Ireland, and Jaques and his wife are buried in St. Stephens Green Cemetery, Dublin. Their eldest son James sailed to Virginia in 1717 and had his own plantation; three of his siblings emigrated likewise and the family has descendants in the USA to this day.